My family survived Holodomor by eating waste left from sugar production | Voices of witnesses

Holodomor survivor Mariia Tilna from Krarkiv Oblast.

Mariia Andriivna Tilna was born on 15 August 1922 in the urban settlement of Kostiantynivka, Bohodukhiv Raion, Kharkiv Oblast. Her village lying halfway between Poltava and Kharkiv was famous for its sugar factory and a steam mill, which were drivers of the local economy from the mid 19th century. However, Ms. Maria can’t remember anything from the wealthy times before the Holodomor. Terrible sights of starving people had overshadowed those earlier memories, who were collapsing in the streets emaciated, and the sour-tasting dry biscuits made from horse sorrel, and watching her two older sisters starve to death.

The Tilnyis family, consisting of father Andriy, mother Paraskovia, and daughters Shura, Nastia, Mariyka, Mariia, and Klava, wasn’t a family of wealthy farmers. “We lived a poor life, there were a lot of children. We had a horse. We had chickens and ducks, but nothing else,” Mariia Andriivna recalls.

Peasants were forced to join collective farms

Ms. Tilna is confident that the Holodomor was organized intentionally. It was preceded by ‘dekurkulization ’, with the following deportations. The people – mainly middle class and wealthy farmers – didn’t want to join collective farms – or kolkhozes in Soviet terms – where all their property was taken away and they were used as slaves. In order to suppress the resistance, the Soviet authorities were deporting farmers to the distant regions of Russia, often hardly suitable for living, “Those who don’t want to go to kolkhoz go to the North to cut the trees there. Who has a horse, a cow, these ones get “dekulakized” and get also sent to the North, to that North. Some came back alive from there; some didn’t. A lot of them didn’t return,” says Mariia.

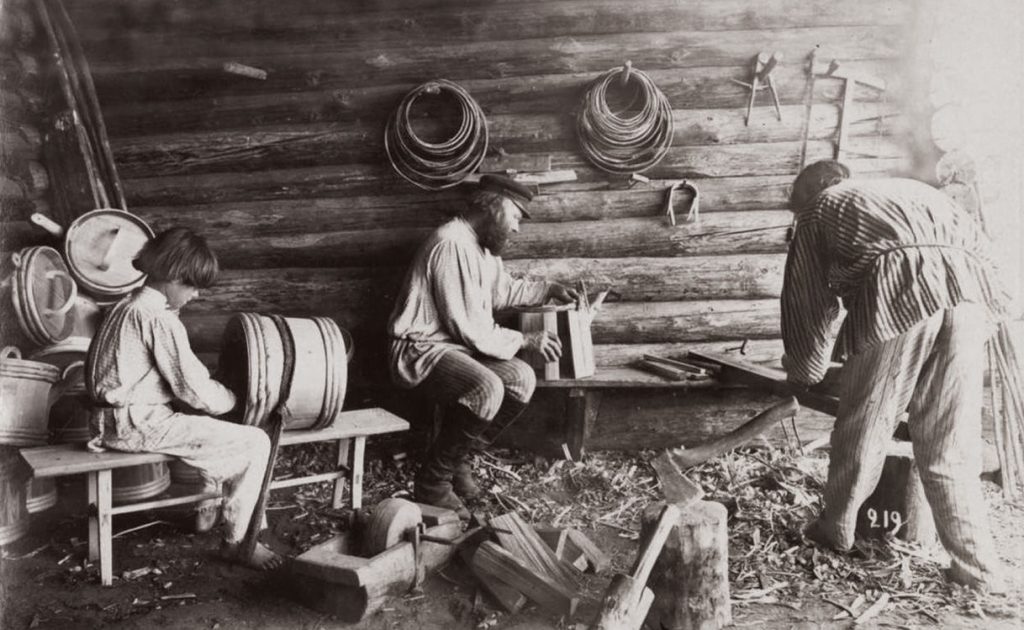

A displaced family of coopers in Siberia. The end of the 19th century. Photo: nv.ua.

After the operation of the “dekulakization,” the Soviet regime launched the Holodomor genocide. One of the methods of its realization, alongside eliminating the church, intellectuals, and fragmenting the Ukrainian world, was the extermination of the Ukrainian farmers who used to be the economic staple of the nation. The genocide was performed by the Soviet activists who went from home to home with searches, taking away all the food. These activists were under the control of “special people” sent by regional authorities. However, the locals were also drawn in to make the food collection more efficient as they knew their village well and the people living there. So the witnesses often knew the activists.

“Those activists were Kuchuhura, Trepolets, back then both women and men were the activists, among the women were Sheichykha, Serafyma,” Mariia recalls the name without a second thought. “I forgot many of them, there were a lot of these activists. The people, who were activists, they were big shots in the village. They become brigadiers – that’s it, they are big shots now!”

The communist activists visited the household of the Tylnyis family two or three times, each time taking away more and more things, even though there was nothing left to confiscate. They would take away not only food but clothes as well. At first, they took away their horse, although according to Mariia, “the horse was rather bad.” Mariia’s father tried to defend his animal, but “it didn’t go his way.” The activists took away even the last foodstuffs – the kidney beans in a glass, and they winnowed the chaff, checking just in case if any seed left there.

In the fall, people had to go to the fields to survive, where something could still be found after the crops were harvested. However, it was strictly prohibited by the terrible ‘The Law of Five Ears of Grain’ enacted in August 1932, under which anyone, even a child, caught taking any produce from a collective field could be shot or imprisoned for stealing “socialist property.” The idea that the land of the Ukrainians is a property of the regime with the people being intruders, deeply rooted in the minds of the witnesses, so that Mariia Andriivna cannot help but call her action any other way than a “theft.”

“We went to steal the ripened ears of grain at night. And there was one woman who had little children, her name was Sekreta. She has four little children, and she went to cut some wheat and got caught, convicted. And she died in jail. Back then, they were putting you in prison if you steal the grains,” recalls Mariia.

Just take a look at her choice of words, “to steal”, “to get caught.” The Ukrainians in the 1930s, who were massively exterminated, at the same time saw themselves as thieves in the situation when their land was violently taken away, while they were forced to work in the kolkhozes for free.

Mariia Andriivna’s hands.

People escaped starvation by eating food waste for cattle

Having nothing to eat while being among the “locked up” fields, Ukrainians had to eat whatever edible was coming to hand. Low on nutrients, the consumed food surrogates were often very dangerous to health, and it wasn’t a rare occasion when people also died from them.

As Kostiantynivka was a local center of sugar production, people consumed the food waste that remained after extracting sugar from beetroots. The beet residue was actually used to feed the cattle.

“We didn’t eat molasses, because they didn’t allow it to us, so we were eating the beet pulp. You know, the pulp for feeding cows? We were stealing the beet pulp, and it was sour a lot indeed and eating away our livers,” Mariia says.

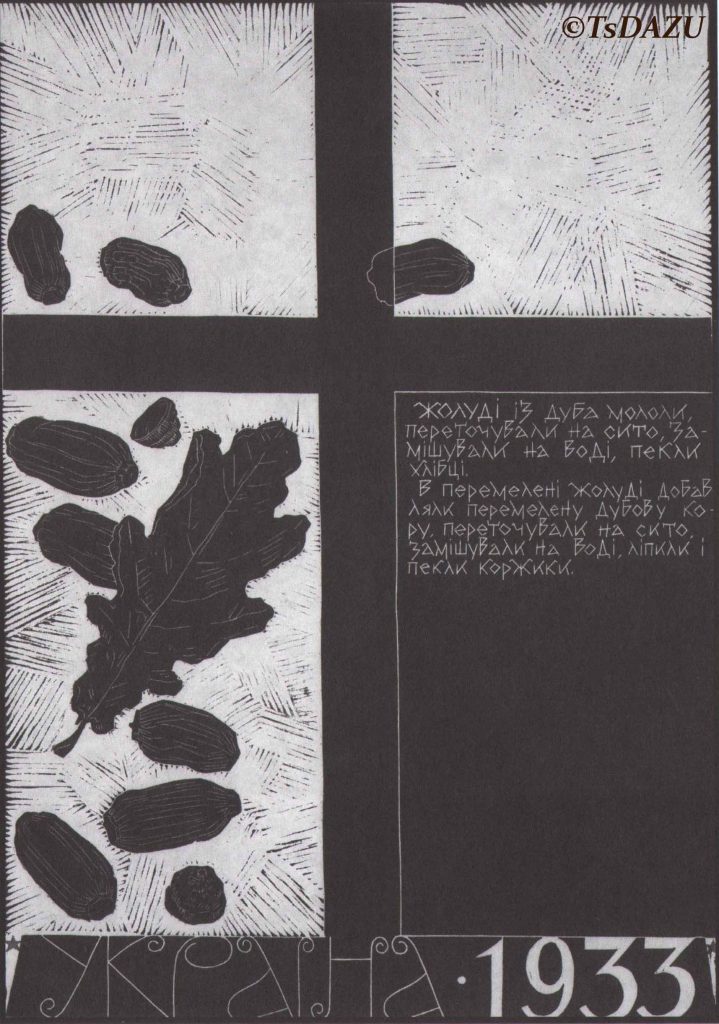

Ukraine, 1933: The Cookbook. The linocuts of M.Bondarenko. New Jersey, 2003.

The “recipe” reads, “Oak acorns were ground, crushed through a sieve, kneaded in water, and small loaves were baked.

In the ground acorns they added ground oak bark, crushed it through a sieve, kneaded in water, molded and baked crackers.” TsDAZU (Central State Archives of Foreign Archival Ucrainica), from the collection of M.Herets.

Furthermore, the witness recalls that the people gathered the horse sorrel. It was hacked or chopped with an ax, and baked into what they called the galettes or dry crackers. Regular consumption of such food surrogates high on acids corrodes the tissues of the stomach, liver, and other digestive organs.

Also, a sudden reinstitution of nutrition, even if it’s surrogates rather than normal food, is also dangerous and it sometimes leads to sudden deaths. In medical terms, it is called “a syndrome of reinstitution of nutrition,” or a “refeeding syndrome.”

The fact is that, during long-lasting starvation, the level of phosphorus in blood drops, and this element is responsible for the production of the energy by the organism, for the functioning of the muscles, and it even is one of the “building blocks” of the DNA. And sudden reinstitution of nutrition after the period of starving of ten or more days causes the refeeding syndrome, which means a sudden surge of phosphorus that leads to the cramps of all muscles. This witness mentions this kind of a situation,“We were very famishing. Who [suddenly] ate a lot, died. Because they ate too much,” Mariia said.

To support the strength of their organisms, people were eating the meat of the dead animals – cows, horses. Mariia Tilna even claims that they ate “zapasky” – pieces of not-fulled wool textile since those were of organic origin.

“We were eating everything we could have,” the witness sums up.

“Even those in kolkhoz weren’t given any food. But chickens in the collective farm were fed. My father’s sister Halia worked in kolkhoz near the chickens. And in the chickens’ excrement were grains of wheat! But the droppings were toxic (she means that it contains saltpeter, which in high concentration causes acute poisonings, – Ed.). So, we gathered that excrement, brought it all home, and started to boil it since there were grains of wheat. And we ate our fill then were intoxicated for two days. But we didn’t die. We got the intoxication,” Mariia says.

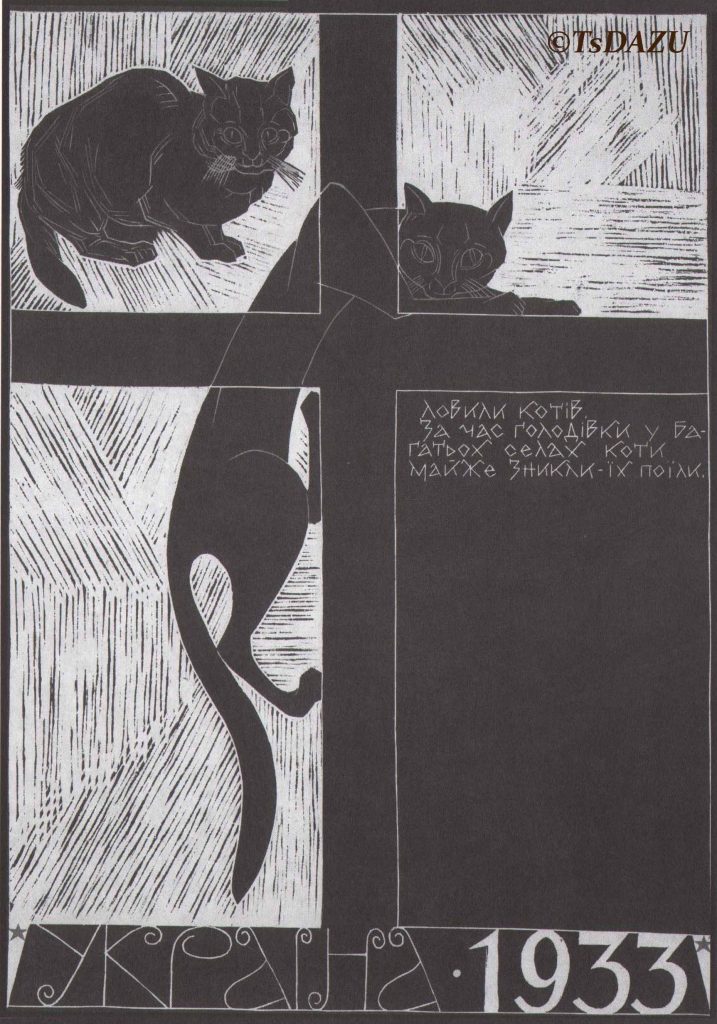

“They were catching cats. During the times of hunger, many villages had almost all cats disappeared – those were eaten.” Ukraine, 1933: The Cookbook. The linocuts of M.Bondarenko. New Jersey, 2003. TsDAZU (Central State Archives of Foreign Archival Ucrainica), from the collection of M.Herets.

Of course, the “food” of this kind is dangerous to health, however, people had only one thing in mind, which was to survive at any cost.

“One old woman ate her baby”

The other scary and unimaginable phenomenon was cannibalism as an extreme level of despair and mental disorder due to starvation.

“One old woman ate her child,” Mariia reveals. “The woman was old, but she did eat her baby. That’s how it was in 1933. It stays forever with you, it is engraved in my mind forever. That woman survived, but she didn’t live long. Her niece took the woman to her house and reproached her: ‘You did eat your child.’”

Body collectors

Holodomor eyewitness Mariia Tilna recollects how people were dying of hunger just in the streets and how those were just thrown in pits:

“The famine in 1933 was very severe. The people were swollen. They walked along the streets, collapsed on the move, and died. And a pit at the cemetery was prepared. I remember that. Many people died; there was a severe, severe famine in 1933. Occasionally it so happened that a person was still alive, but they were already harnessing a horse to a carriage. A still-breathing person was loaded into a cart. Because the pit was ready. They loaded the pit full of people and then shoveled it with the soil. No coffins, nothing.”

According to the National Memory Book of Holodomor Victims, at least 223 citizens of the village died in Kostiantynivka in 1932-1933. It was approximately 10% of the settlement’s entire population at the time. And the figure of those killed during the Holodomor is based on the researched data, but actual death toll could have been much higher.

The Tilnyis family lost two children to the famine, 15-year-old Mariyka, and 10-year-old Klava. To take away their bodies, a carriage arrived at their doors. The bodies of their dead fellow villagers were taken in the same way. As a rule, local authorities appointed some locals to collect bodies from homes. The appointees were chiefly those who owned a horse and a cart. The people were forced to do a horrible job, yet they received at least a minimal supply of food for doing it. They loaded the bodies on their dray and then buried them in a common grave.

Ms. Mariia says that no traces left from the mass graves of the Holodomor victims in her village,

“There is no cemetery with those pits anymore. It was plowed up the place,” she says.

People from across the USSR were relocated to emptied homes of the dead Ukrainians

Since the Soviet authorities were trying to conceal the fact of the Holodomor crime in all possible ways, there was an attempt to erase the memory by destroying the sites of the mass graves, building houses or parks there, laying roads through them. The data on these graves remained only in the memories of the older residents.

When the Holodomor ended, as Maria Tilna recalls, her village had many orphans and desolate houses, later settled by people, often coming from the other parts of the USSR.

The witness of the Holodomor, Mariia Andriivna Tilna

During the next artificial famine, people walked great distances on foot to exchange things for food

Mariia Tilna also survived another massive artificial famine of 1946-1947 in her native village. She recollects that the most common survival strategy was to walk to the city or even to Western Ukraine to exchange clothes or textiles for food. Mariia herself wandered with her neighbors more than once to the West for swapping. She recalls that once they walked the whole day in the bitter cold and asked the locals to spend the night in their home. The locals were already accustomed to the “guests from the East”.

“I knock, the dog barks. A man comes out, saying “What’s up? Are you from the East?” And here we are from the East, and they say, “Uhu, you came to make an exchange,” Mariia said.

This “tradition” of long walking migrations to make exchanges emerged during the Holodomor. Back then Mariia’s parents walked on foot to Kharkiv, 100 kilometers away, where the father’s sister Vasia lived. From time to time, she did her best to help her brother’s family with food. Mariia remembers that in the same way people walked carrying their goods to Krasnokutsk, the raion capital.

Answering the question of how they survived the 1932-1933 Holodomor and the artificial famine of 1946-1947 , witnesses often recall one or two accidents connected with fraud, deception, or the violation of laws – even when the law is the wrongful“ Law on Five Ears of Grain.” It seems that they remember these usually petty accidents because they are still ashamed of their actions.

From today’s point of view, it seems absurd to think about an equal share of bread and surrogates, a burial according to set rites, a value of the family-owned things, a good attitude of your neighbors, when your life is in great danger and you can become the next victim of a criminal policy of the communist totalitarian regime. However, it is these accidents that are somehow captured in human memory as the most vivid ones.

A harrowing of the soil by cows in the M.M.Kotsiubynskyi kolkhoz, of Novobuh district, of Mykolaiv region. April, 1946. The GS Pshenichny Central State Film and Photo Archive of Ukraine.

For instance, Mariia Tilna still remembers well how she “robbed” the head of a machine tractor station (MTS) and framed her grandmother.

“I had an old grandmother. She lived in her own place. She had something (the food, – Ed.). She used to go fishing. I thought I would go to my grandmother, maybe, she would give me some fish. She had a house with a thatched roof. I came and she wasn’t at home. Where was she? And there was a window in the house, that opened in two halves. And my grandmother had a tenant – a director of the MTS. His surname was Sych. And he had everything. Milk, and everything. So, I opened his window, looked whether anyone was there, and entered the house. If that Sych would catch me indoors, he would kill me. I went to the second room, and there was flour, and, what is more, it was white. But I had nothing to put it into. So, I went to the barn, and there were little bags. I took one, poured flour there, and tied it up. And what else? I wondered what was throbbing in the cast iron pot? I looked in there and saw live fish. There was live fish, big and small. So, what did I do? I had a handkerchief, I tied it on my waist and poured in all the fish there…

“I lived alone in a dugout. It was after the war (WWII, – Ed), the famine after the war. I came home and started mixing the dough to make shortcakes, the fish was boiling in the water. I closed up the dugout. There was only a little window with a small pane. The fish is boiling, I’m baking the shortcakes, and it’s when I hear, “Come on, open the door, it’s your grandmother.” Oh, God! I said, “Wait.” And she screamed, “Are you sleeping?” I was scared and hid everything. I opened the door. “Do you know what has happened?” I said, “What?” “I went to the field, then came back home, and they took my fish away, and the flour. So be it. I’m not starving too much now. But if my tenant would come and see it, he’d kill them right on the spot.” And until her death, I didn’t confess what happened to her food and that I stole it.”

Local church was destroyed

The village of Kostiantynivka had not only the human losses. The communist totalitarian regime also caused damage to the cultural life of this area. Mariia Tilna remembers how during the Soviet anti-religious campaign, the local church, built back in 1780, was taken apart.

“It was a good, real church (she probably means the wooden church of St.Kostiantyn and St.Elena, taken apart in 1939, – Author). And the real bells. When the bells rang, they were heard in Kolomak (a settlement 30 km away, – Ed). And they started to do it, they trampled, burnt everything near the village council. But that bell ring was so good. They came, took it down, cut it into pieces, and took it away to melt it. They burned down the icons, trampled them with feet, and… All things were happening. We survived everything, all the grief, all the terror.”

Local citizens took the relics home to save them. It was a common practice at that time. Mariia’s mother took one of the icons as well. It was a “big icon, all covered in shumys,” i.e. tin-decorated, according to her.

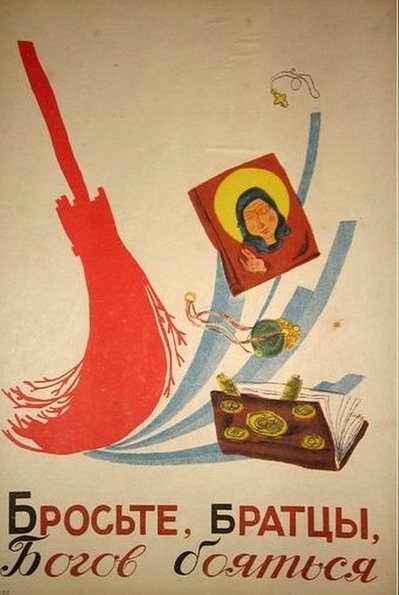

Soviet anti-church ad reading “Brothers, stop fearing gods.” M.M.Cheremnykh.

Anti Religious alphabet/ABC. Leningrad-Moscow: Utylbiuro Izogiza. 1933

Kobzar musician was among Holodomor victims in Kostiantynivka

Kostiantynivka was also the hometown of popular wandering folk singer Pavlo Petrovych Hashchenko, who played the traditional music instruments kobza and lyra. The musician performed in his area, was an often guest in Kharkiv, Poltava, Chernihiv.

Before the Soviet occupation of Ukraine, his talent was highly appreciated among the Ukrainian intellectuals. The communist regime persecuted Ukrainian kobzars and lirnyks, and Hashchenko was among those. Eventually, Pavlo Hashchenko became one of the Holodomor victims. He died in 1933 and was buried in his Kostiantynivka at the old cemetery. His grave is lost now.

Portrait of P.M. Hashchenko by O.Slastion. 1905.

Mariia says that her family and her village always remembered the Holodomor. However, due to the loss of the mass gravesites, the destruction of the church, and the departure of many citizens from the village, and the total decay in the population area after the closure of the sugar factory, the local memory of the Holodomor remains poorly explored by historians and has been slowly disappearing. Maria Tilna is one of a few memory bearers of this page of our history, one of the last witnesses in her area.