The Holodomor in Velyka Lepetykha in the Kherson region: a historical and local lore study

This year, the team of the Holodomor Museum has carried out a series of research expeditions, traveling 10,000 kilometers across Ukraine, searching for the Holodomor witnesses of 1932-1933 and still unknown places of mass graves of the genocide victims. The most substantial evidence formed the basis of 10 multimedia materials of the project “Holodomor: a mosaic of history. Unknown pages.

The last publication of this series includes the stories of how Velyka Lepetykha and Kniaze-Hryhorivka villages of the Kakhovka district of the Kherson region survived those times.

Dnipro Plavni as a historical area of Ukraine

Dnipro Plavni is a unique natural complex with rich fauna and flora. Unfortunately, most of the floodplains were flooded due to the construction of the Kakhovka HPP dam in the 1950s. At the same time, both biological diversity and a part of Cossack history – the Velykyi Luh area – were lost. The Cossacks actively carried out their economic and military activities in the floodplains. Small rivers, floodplain meadows, and lakes teeming with fish and wildlife comprised the natural floodplain complex. The natural complex of floodplains consisted of small rivers, floodplain meadows, lakes rich in fish and wildlife.

Lepetykha was the name of one of the rivers in the floodplains that had Cossack winter harbors on its banks. The first permanent settlements appeared at the end of the 18th century on the site of former Cossack winter harbors, the largest of which was Velyka Lepetykha village. Cossack winter harbors, the largest of which was Velyka Lepetykha village. Its name probably comes from the name of the river. In these parts of southern Ukraine in the nineteenth century, agriculture was actively developing, giving impetus to economic development. Evidence of this was perhaps the largest annual fairs in the whole region in Velyka Lepetykha, which attracted people from all over the region.

Despite the turbulent events of the early twentieth century, Velyka Lepetykha remained one of the largest and wealthiest villages in southern Ukraine, with about 4,000 yards.

The first significant blow to the region was the mass artificial famine of 1921-1923.

“That year, many families went hungry… I recall Misha Droga, who frequently came to us for a crumb of bread, but his legs were swollen and infested with worms. “Many people died of famine, both adults and children,” says Olena Kutishcheva about the famine of 1920, who was born in Velyka Lepetykha in 1913. (The original language of the witnesses has been preserved.)

Kutishcheva Olena Borysivna, born in 1913

And yet, later in the short period of the NEP (New Economic Policy introduced by the Bolsheviks in the early 1920s, which provided elements of a market economy, including the right to sell agricultural products after paying food tax – Ed.) Residents of Velyka Lepetykha were able to resume their farms. Many of them became successful farmers and had quite large fortunes.

“Mother’s father. Lyapatysky. His last name is Pavlovsky. Well, they were wealthy, because on the main street… there is such a huge shop on the street – that’s all they had. And in the garden, there were houses, well…, wooden ones. Well, there were three or four barns. They rented barns for people, and people brought grain there in these barns. Well, they were so rich,” tells Anna Lavrentiyivna Babenko, a resident of Velyka Lepetykha.

Dekulakization

However, the communist totalitarian regime soon launched a campaign of dekulakization – the destruction of the stratum of wealthy farmer owners who were the economic basis of the Ukrainian nation.

We can judge the scale of dekulakization from the diary entries of one of the “activists” – Makar Kryvtsun:

“In 1928, I moved to Lepetykha and was appointed commissioner for the liquidation of kulaks, NEPmen, and speculators as a member of the village council and the district council. As a representative of both the people’s court and the council’s executor, I worked diligently to complete this assignment.Almost every day from the sale of NEPmen and speculators’ property, I handed over to the cash desk of the District Executive Committee (10) ten thousand rubles.” (Translated from Russian by Makar Kryvtsun’s memoirs).

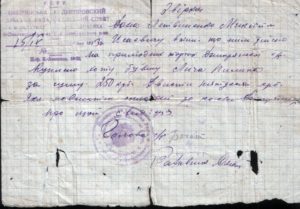

The information letter about that the Litvinenkos bough tthe house of the dispossessed Lych for 250 rubles shows that the 10,000 rubles that activist Kryvtsun gave to the cashier every day, selling the property of “NEPmen and speculators,” then amounted to 40 houses.

Certificate of purchase of the house of the dispossessed Pylyp Lych (stored in the funds of the Velykolepetysk village folk museum of local lore named after Olena Tsipko).

The memory of those times in Velyka Lepetykha is a dilapidated barn building that once belonged to the same “kulak” Philip Lych. Even now, the house is impressive in its size. In 1941, during the German occupation, Pylyp Lych’s wife briefly regained the farm taken away by the Bolsheviks, but in 1944 Litvinenko took back the house again.

When the issue of compensation for repressed families arose in the early 1990s, descendants of “kulaks” and other “enemies of the people” were never given back their ancestral property. Some received pitiful monetary compensation, which quickly depreciated due to inflation in the early 1990s. However, this process yielded at least one positive result – thousands of kulaks were rehabilitated, and criminal convictions were declared illegal.

The barn of the dispossessed Pylyp Lych. October 1, 2021. Photo: Holodomor Museum

The dekulakization reached massive proportions: the inhabitants of Velyka Lepetykha and the surrounding villages were relocated to the Kayirs’ka Balka (located about 30 km from Velyka Lepetykha) with infertile soils unsuitable for agriculture.

“The first dispossessed people were deported to Kayirs’ka Balka. Well, there is a layer of natural soil about eight or ten centimeters and then below – a stone, “- said Mykola Marchenko, a local historian, director of the Velyka Lepetykha village folk museum of local lore named after Elena Tsipko.

Kayirs’ka Balka. Source: Wikipedia

Witnesses of the genocide of Ukrainians from other villages also tell about dekulakization

“They were evicted… They were not allowed to build anywhere on flat land. They dug that dugout in the beams. And my mother took me there. I still lived with them for a while. And as soon as my grandfather got used to it, he was a blacksmith, and the kolkhoz called out to him to do something for them. So they gave him something. And I lived near them. They came back. Are you here already? Well settled. They expelled him again,” recalls Tamara Konoshchuk, who survived the Holodomor in Kniaze-Hryhorivka village near Velyka Lepetykha.

The communist totalitarian regime left the evicted “kulaks” with little chance of survival. Although, in such extreme and unfavorable conditions, the real masters managed to provide for themselves and their families.

Then the regime went further and deported the “kulaks” to Siberia. This fate, in particular, befell Tamara Konoshchuk’s relatives:

“And two sisters married wealthy men, kulaks.” As a result, they were sent to the North. Aunt Shura had two children, who froze, died, and were thrown out on the way… And they were taken there. And they came back after the war. Vera and Shura. There were no men.”

Grain procurement

The so-called “dekulakization” was just the beginning of the troubles that Ukrainians faced in the late 1920s and early 1930s. After the repression against the most active and most dangerous part of society for the communist totalitarian regime, court searches began under the pretext of implementing so-called grain procurement plans, which were, in fact, one of the mechanisms of genocide.

However, materials of the party’s purge in the Velykolepetisky district in December 1932 show that some local officials were aware of the unreality of the grain procurement plan and refused to follow the instructions of the “leadership.” Many of them paid for it not only with positions and party tickets but also with freedom.

In particular, Communist Party member Myna Ivanovych Maiboroda, who worked on the “grain procurement front” in the area where the grain procurement plan was 20% fulfilled at the time, refused to head the kolkhoz and exploit his fellow villagers:

Tamara Konoshchuk also remembers well the confiscation of fish caught by locals, in the rivers, which were rich in fish in the Dnipro floodplains:

“Fishermen with nets. Well… They caught fish, fish. Well, but no one gave it. No way! They took away everything. They handed everything over. And just try to take it home… Well, maybe someone could hide it in his bosom. ”

After forcibly transferring most Ukrainian farmers to collective farms, the regime gained millions of disenfranchised and free laborers. People worked for “trudodni” (working days), for which they provided almost no food.

“They paid (laughs, – Author) they wrote sticks then. And for those sticks… It was called one ‘trudoden’ (working day). Or one and a half “trudoden’ ” She went to the kolkhoz, and there were pigs… the collective farm bred. She was a pigsty there. So she was around the pigs and grazed, that’s how she walked. In general, she was a shepherd. And we were sitting at home near the gate, my mother was gone. We lie at the gate, waiting for our mother, maybe she would bring… And we fell asleep. She came and we slept. That’s how it was.” tells Tamara Konoshchuk about the“ payment ”for work on collective farms.

Konoshchuk Tamara Stepanovna, born in 1928 Photo: Holodomor Museum

The so-called “contract agreements” that the individuals signed with state and cooperative procurement organizations were the reason for food searches and confiscation. According to them, the farmers agreed to give the state a predetermined amount of grain. These commitments were made by force in the late 1920s. However, because the contractual “norms” were unrealistic, the farmers were deprived of actually all of the grain available to them.

The contracting system was abolished in 1933, and so-called “firm tasks,” which were mandatory, were introduced to farms. The principle of contractual relations between agricultural producers and the state was even formally abolished as a result of these innovations.

Signing of a contract agreement in the village of Velyka Lepetykha. 1933. From the archives of the Velyka Lepetykha Village Folk Museum of Local Lore named after Olena Tsipko

Mass mortality

Based on eyewitness accounts and historians’ research, we can claim mass deaths in Velyka Lepetykha and surrounding villages in 1932-1933.

“ People were walking, swollen. Here they were lying on the street. Mom went to the steppe. In the past, mice used to bring grain, making such pits. They hid it in the ground. And people collected those ears of grain and brought them home. Then they used to make some porridge. And next door, I know, was a mother alone, a mother with a breastfed child. There was no one, the man was somewhere at work, maybe. And she could not endure with the child. The baby was sucking breast. Oh no, hungry mother and child. And she wanted to go outside. She fell in the hall and was lying dead, and the child was sucking the breast,” said Tamara Konoshchuk.

Local historian Mykola Marchenko claims that the death rate in Velyka Lepetysa reached a third of the total population:

“How many people died? I carried out the statistics, counting those people who testified, then about a third, a third of people died. About a third. ”

Exhausted from hunger, Ukrainians could no longer bury properly their relatives, friends, and neighbors who died of famine in compliance with traditional rituals.

“Their daughter-in-law, Sonia’s, was with her brother, she lived near the graveyard, and she told me there was no one to dig holes for, everyone was weak… It had nothing to do with whether they wrapped it in rags because there was no coffin, although the floodplain was like that, but what then… ” terrible memories of Tamara Konoschuk.

One of the places of mass graves is located on the outskirts of Velyka Lepetykha. After the restoration of Ukraine’s independence, the public of the village honored the innocent victims of the Holodomor genocide.

“During the Holodomor, according to people, there was a chapel here, where people slipped to die. In winter, near this chapel were piles of the dead, because there was no one to dig big holes. In the autumn and spring, large pits were dug there, like silage, to which people either slipped to die themselves, or they were brought there and stacked. There is even evidence I’m not sure how to handle it, that they buried the half-dead. That is, people were not dead, but they were taken away,” Mykola Marchenko explains.

Place of mass graves in the village Velyka Lepetykha

Another location where the bodies of those killed during the famine of 1932-1933 were brought, is located on the area of the modern park, that has been recently named after the Holodomor victims. According to historian Mykola Marchenko, there was a graveyard on this site, which was destroyed in the 1980s, where Victory Park was built.

“Victory over the Holodomor victims,” jokes the local historian.

A cross and a monument were erected on this site. Nearby is St. Nicholas Church.

Local historian Mykola Marchenko at the site of the mass graves of the Holodomor victims in the village Velyka Lepetykha. Photo: Holodomor Museum

In the neighboring village Kniaze-Hryhorivka, the mass graves of the Holodomor genocide victims have not been maintained, and no memorials have been erected there. These places are located on the territory of former graveyards, which are now overgrown with weeds and are used for grazing cattle.

Place of mass graves of the Holodomor genocide victims in the village Kniaze-Hryhorivka

The Holodomor genocide reaped its bloody harvest in the originally agricultural Tavria, where Velyka Lepetykha stretches on the banks of the Dnipro. Hundreds of people were dekulakized and evicted, and thousands remained starved to death. Neither the Dnipro floodplains, rich in fish and other resources nor fertile soils nor even the efforts of individual party members to defy orders from above could undo or mitigate criminal decisions to exterminate Ukrainians at the highest level.However, the memory of the Holodomor in the region lives on in the memories of witnesses, in monuments erected at the sites of mass graves of victims, in buildings preserved from the 1930s to the present, in studies of local historians who are restoring the truth according to archival documents.

Interviews with Mykola Marchenko, Tamara Konoshchuk and Hanna Babenko were recorded during the expedition to the villages Velyka Lepetykha and Kniaze-Hryhorivka, Kakhovka district, Kherson region, as a part of the project “Holodomor: Mosaic of History. Unknown Pages ”, implemented with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.