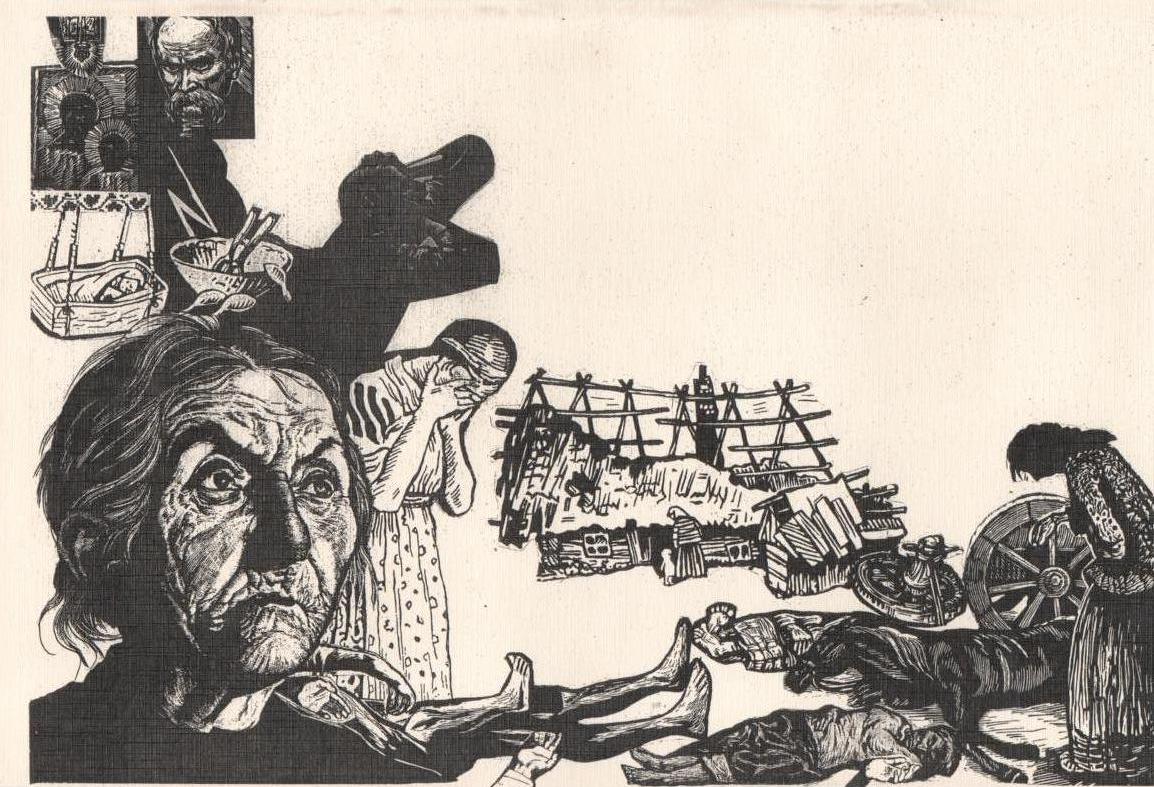

Social anomalies and deviations during the mass man-made famine of 1921-1923 in Ukraine

Abstract. The article analyzes the precedents of antisocial behaviour and deviations in Ukrainian society, which manifested themselves under the influence of the mass man-made famine of 1921-1923. It characterizes the causes, manifestations and consequences of prolonged starvation for the person’s psychophysical state.

The mass man-made famine of 1921–1923 covered all regions of Soviet Ukraine. Southern Ukrainian provinces were the most affected by the famine: Katerynoslav, Zaporizhzhia, Mykolayiv, Odesa, and Donetsk. Poltava, Kharkiv, and Kremenchuk [1] were in a difficult situation, where from 30 to 80% of the population was starving. [2] The mass man-made famine of 1921–1923 was a consequence of the Bolshevik occupation of Ukraine. It was the food policy of the communist regime that became the principal cause of the mass man-made famine: pro-rationing, postponement of the NEP, the forced export of Ukrainian grain to help the “starving people of the Volga region”, the Bolsheviks’ attitude to the famine in Ukraine as a “disease”, ignoring the daily needs of Ukrainians – all this in a complex led to to the mass death of Ukrainian.

The everyday life of the surviving Ukrainians also changed radically. The criminogenic situation worsened: homeless people and beggars filled stations, streets, and even cemeteries. Notices in the columns of local newspapers with the eloquent headlines “Beastly murder in Karantynka” (or in any other area) became commonplace. Even district party committees stated that “small gangs of thieves and lone criminals are so rampant that farmers had to hide their horses and pigs in their houses at night because there is neither rescue nor effective countermeasures against crime. As a result of the famine, criminal offences and corruption became almost the main sources of food supply.Food thefts by canteen employees became widespread. [3] Even in children’s institutions – shelters, nurseries, schools -, thefts were constantly recorded. The head of the Mykolaiv branch of the Council for the Protection of Children stated that children stole from their own staff, and there were recorded cases when children from one children’s shelter attacked pupils from another. At the same time, the attacks took place with particular cruelty: they threw a handkerchief over the victim’s face, and strangled, so everything possible was removed. [4]

During the years of mass man-made famine, social anomalies became particularly acute. Social orphanhood, the practice of mothers abandoning their children or abandoning babies, became widespread. [5] In particular, Anastasia Tsapkova from Huliaypole, citing the fact that her husband, a Red Army soldier, was killed by the Makhnovtsi, demanded that her two, three, and five-year-old children be taken to the orphanage. [6] The mother of three-month-old Andrii Serksen refused him only because she was poor. The practice of parents abandoning their children became widespread for various reasons: from the death of parents from hunger to the inability to raise children due to impoverishment. [7] It can be argued that abandoning children became a new phenomenon in Soviet everyday life. Traditional Ukrainian society hardly knew such precedents. Single cases were publicly condemned.

Child homelessness, which was not inherent in the Ukrainian para-civil society, was growing fast. If at the beginning of the 20th century, as a rule, orphaned children were taken by relatives, sometimes orphans were arranged for upbringing in monasteries, then, as a result of the First World War, such an antisocial phenomenon as child homelessness became widespread. However, it turned into a blatant social problem during the massive artificial famine of 1921-1923. Children who lost their parents were left unattended and forced to beg. As a rule, they tried to reach crowded places – markets or railway stations, where they begged. The appearance of a homeless child was typical: dirty, barefoot, and in worn clothes.

Poverty and misery influenced the growth of bitterness. Children gathered in gangs and committed petty thefts. Homeless children often used to travel from one city to another. The southern Ukrainian cities were especially “popular” because there were legends about mythical prosperity there. There, neglected children often ended up in the police, where they were registered, then they fled and again illegally moved to another city, adding to the ranks of the homeless there.

Various forms of deviation manifested themselves: anthropophagy based on clouding of consciousness, necrophagy, cannibalism, corpse-eating, and infanticide. Unfortunately, the precedents of cannibalism were not isolated. In Zaporizhzhia, 45-year-old Kharytyna Nyshchenko, a mother of 11 children, strangled two of her children (a five-year-old daughter and a seven-year-old son) due to prolonged exhaustion and ate them [8]; Hryhorii Shcherbaha first begged for alms, and then killed his two children and a neighbour’s girl and ate their meat together with the older children. [9] In total, in June 1922, 25 cases of cannibalism were recorded in the Zaporizhzhia province. [10] The Velykovyskivsky volost executive committee recorded cases when mothers drowned babies they could not feed. [11]

The practice of rallying young men into armed gangs aimed at kidnapping and killing women and children and eating their organs was spreading. [12]

Corpse eating also became widespread. A peasant woman from Yurkivka named Psheniak cut off the dead girl’s legs, boiled them and ate them together with other children. Note that these are official statistics, hidden deviations, regrettably, were significantly higher. Not all crimes were recorded, and not everything was investigated.

According to Professor Franko’s conclusions, the mental sphere of those starving is under the influence of severe depression and the effects of boredom, which leads to disorders of the coordination of mental elements and complicated complexes that form a mental personality. Attention is completely absorbed by internal sensations. [13]

The consequences of mass man-made famine turned out to be long-lasting. We mean not just the economic but, first of all, the humanitarian component. People’s psychology changed: many Ukrainians had to humiliate themselves to receive pitiful food, some had to lose their moral face and resort to theft, and people’s anger and hatred intensified. According to the doctors’ studies, hunger gives rise to bitterness, greed, cruelty, misanthropy, and immorality. Hunger can activate a person’s atavistic instincts.

[1] Famine of 1921-1923 in Ukraine: Collection. documents and materials / Edit. O. Movchan; Rep. Ed. S. Kulchytsky / Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Institute of History of Ukraine. Kyiv: Nauk. Dumka, 1993. P.117.

[2] Famine of 1921-1923 in Ukraine: Collection. documents and materials / Edit. O. Movchan; Rep. Ed. S. Kulchytsky / Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Institute of History of Ukraine. Kyiv: Nauk. Dumka, 1993. P.137.

[3] DAZO. F.R-75. Op. 1. Issue 46. Sheet 6.

[4] Famine of 1921-1923 in Ukraine: Collection. documents and materials / Edit. O. Movchan; Rep. Ed. S. Kulchytsky / Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Institute of History of Ukraine. Kyiv: Nauk. Dumka, 1993. P.127.

[5] DAKO. F. R-1074. Op. 1. Ref. 43. Ark. 66.

[6] DAZO. F.R-208. Op. 1. Issue 122. Ark. 59.

[7] DAZO. F.R-208. Op. 1. Issue 122. Ark. 50.

[8] DAZO. F. R. 2. Op. 1. Ref. 354. Ark. 30.

[9] DAZO. F. 1241. Op. 1. Ref. 1803. Ark. 1-13.

[10] DAZO. F.R. 2. Op.1. Issue 323. Ark. 197, 198.

[11] DAKO. F. R-1074. Op. 1. Ref. 43. Ark. 66.

[12] Famine of 1921-1923 in Ukraine: Collection. documents and materials / Edit. O. Movchan; Rep. Ed. S. Kulchytsky / Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Institute of History of Ukraine. Kyiv: Nauk. Dumka, 1993. P.207.

[13] Famine of 1921-1923 in Ukraine: Collection. documents and materials / Edit. O. Movchan; Rep. Ed. S. Kulchytsky / Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Institute of History of Ukraine. Kyiv: Nauk. Dumka, 1993. P.207.

Roman MOLDAVSKY,

Senior Research Fellow

of the “Holodomor Research Institute” branch

National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide,

Inna SHUHALIOVA,

Senior Research Fellow

of the “Holodomor Research Institute” branch

The National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide

Illustration by artist Mykola Hnatchenko.