“A repressive machine miraculously bypassed my father twice”: Lavro Nechyporenko’s son Oleksandr shared his memories of his father

This manuscript of a 96-page notebook entered the collection of the Holodomor Museum three years ago. And this was preceded by a separate dramatic story. The manuscript was created at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s, which already makes it special. Since, at that time, it was a Sisyphean work that would definitely stay “on the table”. But the author had a great need to talk about “those black days of national grief, which he was a sad witness of.” And still hoped to be heard. Lavro Nechyporenko handed over the notebook with notes to his friend, associate, also, a teacher from Boyarka, Ivan Kovalenko. I wanted to know his opinion because Kovalenko was already then a well-known dissident poet who belonged to the circles of the sixties. And then the friends probably intended to publish the text as a self-publisher, which Ivan Kovalenko actively distributed.

However, Kovalenko himself was already under the hood of the KGB and in January 1972, during the infamous pogrom of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, he was arrested. The notebook with Lavro Nechyporenko’s notes was seized during the arrest along with another self-published and attached to the case. Only many years later, in 1996, they returned the “arrested” archive to the already rehabilitated Kovalenko. Lavro Lavrovych, who passed away in 1977, did not wait for the return of his manuscript from “exile”, considering it lost forever.

In 2019, the local historian and researcher, and now the spokesman of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, Andrii Kovalev, decided to learn the archival file of the dissident poet in the Branch Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine. Looking through the list of the confiscated documents and works, he came across the name “The 33rd year”. Realizing what a unique and valuable thing it is, he convinced his relatives – the Kovalenkos and the Nechyporenkos – to hand over the finding to the Holodomor Museum.

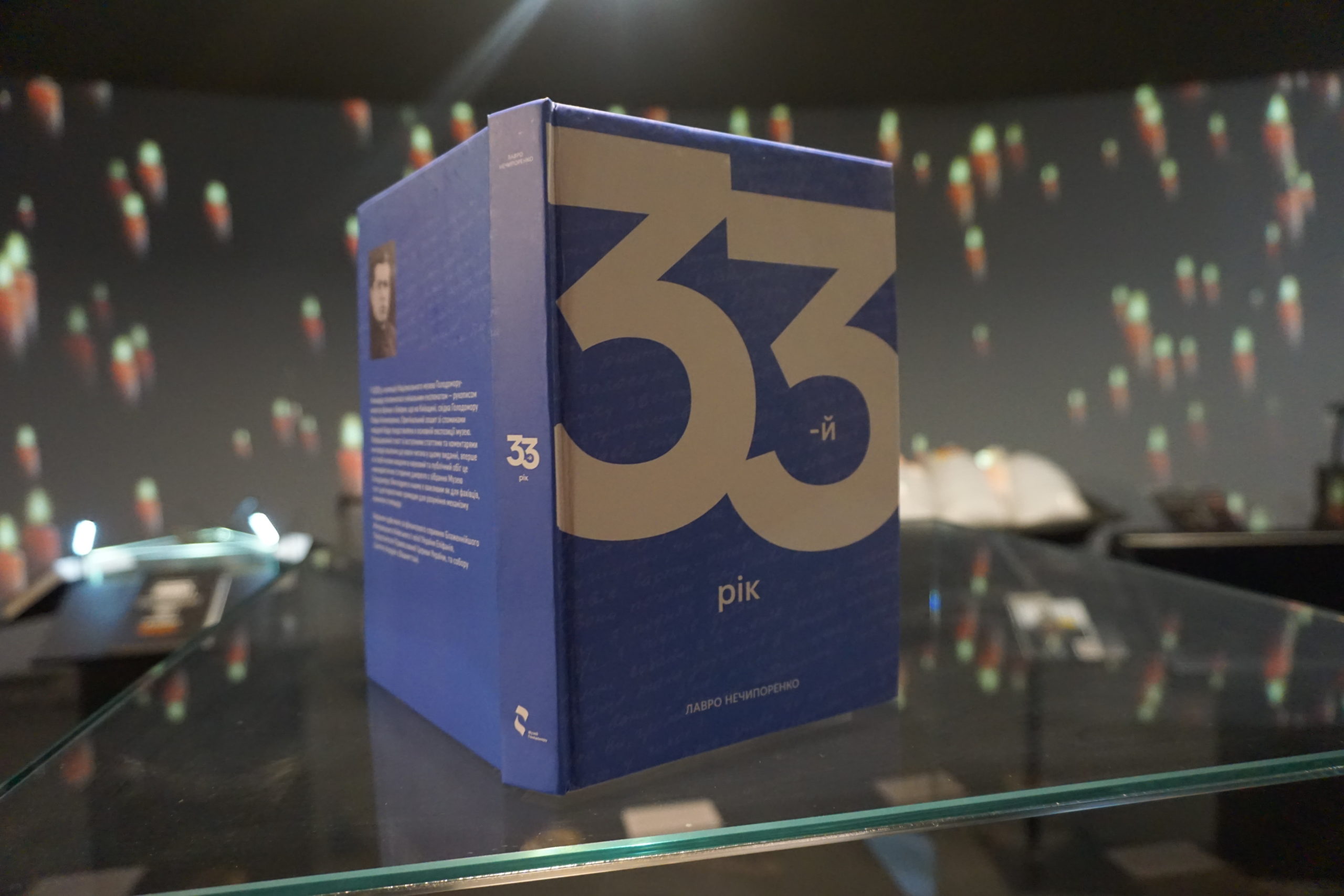

And finally, we managed to fulfil Lavro Nechyporenko’s dream and publish the manuscript. The book presentation will take place on the 8th of February at 11:30 in the Holodomor Museum. We invite everyone.

We asked Lavro Lavrovych’s son, Oleksandr Nechyporenko, to tell more about his father and the history of the manuscript creation, who in 1990-1994 was a People’s Deputy of the Verkhovna Rada of the 1st convocation.

“My father liked to record events. He said: “Maybe someday someone will read it”

Mr Oleksandr still lives in Boyarka, near his parents. Even the old parents’ house was preserved – Mr Oleksandr, an avid collector and collector of antiques built a museum in it.

The host takes us to a small hut where a large Nechyporenko family once lived. At first, it was just two small rooms, in one of which there was also a stove. Much later, when one of the sons got married, a room for the young family was built on the other side of the house.

The memoirs “The 33rd Year” were once written under the roof of this house.

“Father always kept some records. I often saw him writing something there. But living conditions were so hard that he did not have his own corner to sit down and work quietly. Although my mother tried to facilitate it as best as she could. He was a headmaster and a teacher, and this was constant work with papers, checking students’ homework – always such piles of notebooks (shows). Every evening he would sit by the lamp and do this.

When he retired in 1961, he finally managed to pay more attention to his favourite occupation. It was then that he focused on this work about the 33rd year. And besides, I remember him collecting and systematising Ukrainian surnames. Then he began to write the work “Eagle’s Nest on the Swamp”, in which he wanted to analyse the history of the creation of the Russian Empire (the title itself says a lot). I also knew that he had records of front diaries. That is, all this indicates that the father had a desire to record thoughts and events. He used to say when I was a child, “Well, maybe someone will read it someday.” That is, he still hoped that what he wrote would reach people one day.”

The family of the Nechyporenkos was large. Lavro Lavrovych (born in 1899) and Lepystyna Klymivna (born in 1912) tied their destinies in adulthood – both had already been married before. The first husband of Lepystyna Klymivna did not return from the Finnish war. Lavro Lavrovych’s family life didn’t work out either: because of a war injury, one hand was not working well, and rural life involved a lot of hard work, which created various misunderstandings.

“My parents started their relationship when each of them already had several children. My mother has four boys, my father has three, and I am already a common child, which strengthened their marriage. In total, there were eight of us with my parents – six boys (Volodia, Borys, Vitalyi, Valentyn, Petro and I) and two girls (Halyna and Hanna). That is why our family was crowded and noisy all the time… All the children were relatives to their father and mother and relatives to each other. We really had a very good and friendly family,” Oleksandr Lavrovych fondly recalls those times.

His parents were both from the village of Yerchyky, Popilnya district, Zhytomyr region.

Oleksandr Lavrovich was born in the same village in September 1947. When he was four years old, the family moved to Boiarka, Kyiv region, where the head of the family was offered a job at railway school No. 18.

However, little Sashko continued to spend the summer in Yerchyky with his aunt Maria Palamarchuk.

“Graceful land, very beautiful places. On the banks of the Unava, near an oak forest. I remember, in my early childhood, we would go to an oak grove, and between the oaks there would be a hazel covered with nuts in the autumn. We would collect those hazels and hit them with hammers… And there were so many mushrooms! And fish in the Unava – pike, carp, crucian carp, and roach – whatever you want! There was a three-person crew of fishermen in the collective farm. At that time, people were even given a portion of fish on trudodni (English: labour days). I remember how a big boat docks at the shore – and there were (showing) such things: loaches, pikes, and whatever you want,” says Nechyporenko.

How could people starve and die of hunger in such a rich land? Lavro Nechyporenko also writes about this in his memoirs: how forced collectivization was carried out, how the kulaks were dekulakized and who became the kulaks, how their looted property was sold and how the farmers were ashamed to buy anything because they knew those “kulaks” well…

“I heard about the Holodomor from my parents from an early age. There were no forbidden topics in our family. Although worried about the safety of his relatives, the father did not dare to tell about everything. Especially about his direct participation in the events as part of the armed forces. The probability of such participation is evidenced by his mention of the Sich Riflemen. This could be described not just by an observer, but only by a direct participant in the events. I heard about the Liberation Competition from him when I was still a teenager, at the age of 12-13. For example, I first heard the now-popular song “Oy, u luzi chervona kalyna” (eng. – Oh, in the meadow red viburnum”) from my father at that time.

The uncle was arrested simply during the district teachers’ conference

The formation of Lavro Lavrovych’s worldview was significantly influenced by Denys Bychenko, his elder brother.

“He was a teacher, had a large library. By the way, I still have a couple of books that belonged to Uncle Denys. Although I never knew him personally because he was repressed in 1937.”

The uncle was arrested during the district teachers’ conference in Popilna for participating in allegedly counter-revolutionary activities and anti-Soviet agitation. He was sentenced to be shot by the infamous “troika”. The sentence was carried out on the 17th of November 1937. Lavro Lavrovych never learned about his brother’s fate although he contacted law enforcement agencies. However, during the Soviet Union times, his requests remained unanswered.

“Under the influence of his brother, my father strove for knowledge from childhood, and received a good education at that time: after graduating from the parish school, he studied at the teacher’s seminary in Korostyshev, from where he transferred to pedagogical courses in Kyiv (now Borys Grinchenko Kyiv University). The teaching work there was at a very high level and the teachers were excellent. For instance, musical disciplines were taught by Kyrylo Stetsenko and Mykola Leontovych. By the way, my father was even in charge of the library in this seminary because all his life he was passionate about books, and he always had a good library. He felt really sorry that his large book collection was lost during the war… Later, my father enrolled in both the Institute of National Education and the Polytechnic Institute. However, it was difficult to study at two universities simultaneously, so he had to leave Polytech.

And then – teaching work. He taught in many schools in Kyiv, in his native Yerchyky, in the neighbouring village of Romanivka… He taught mathematics, astronomy, and history. He substituted for many teachers at our school. He was a man of encyclopedic knowledge – whatever you would ask, he would tell you.”

“In January 1933, the father was arrested”

A repressive machine miraculously bypassed Lavro Nechyporenko twice, although it passed almost at close range.

In January 1933, he was arrested, and accused of involvement in a counter-revolutionary organisation. He allegedly contacted this organisation through a former employee at Panteleimon Yarosh Labour School No. 38.

“My father really knew him, met him several times, was at his house – that’s all! Yarosh himself was sentenced to 10 years in the camps. Already during his stay in prison, he was repeatedly summoned, interrogated, and he probably called everyone he knew, just to get off the hook. So somewhere my father’s name flashed. As a result – arrest. But the investigation did not even have anything to cling to. As a result, all these nine souls who were involved in the case were, fortunately, released. However, having visited Lukyanivka, in those millstones of the system that ground people by the thousands, he saw a lot. So I wanted to share what I felt then and what people like him felt.”

He described his stay in the Lukyanivka prison in the first part of his memoirs, “The 33rd Year.” When Nechyporenko got out of prison a few months later, he saw what was happening at that time behind the walls of the prison, where terrible news was also coming from the outside. He was sent to the village of Novofastiv (now Vinnytsia region) to help collective farmers because there was simply no one to harvest in the starving villages. On the way to Novofastiv, he stopped at his native Yerchyky saw his village in the agony of hunger, and learned about the death of three of his uncles and many fellow villagers.

“I remember my father burning some of his records in the garden”

When the memoirs about 1933 were ready, he handed over his notes to Ivan Kovalenko, who had contacts with the Sixties and self-published them. There was a considerable age difference between them – 20 years. But their views were very close, so they immediately became friends.

“Ivan Kovalenko was a very interesting, capable man, engaged in a lot of self-education. He knew several languages – English, Spanish, French, German (it will become known later that the KGB conducted an operational investigation on Kovalenko, in which he appeared as a “Polyglot”. – Author). When I came from the army and decided to enter the law faculty of Shevchenko University, I took English lessons from Ivan Yukhymovych. He himself was constantly engaged in self-development, and he tried to instil in me not only the desire but also the ability to learn.

Through Ivan Yukhymovych, we received samizdat (self-published items), perhaps even first-hand – both from Sverstiuk and Chornovil. And through me – sometimes to students, my fellow students. My father copied those typewritten texts by hand, and those manuscripts have survived to the present.”

Oleksandr Nechyporenko is taking old general notebooks from the shelf, opening them and showing “Internationalism or Russification?” by Ivan Dziuba, transcribed in his father’s small, neat handwriting…

Kovalenko’s arrest in January 1972 was unexpected and shocking.

“I remember how my father and I were invited to Korolenko one day – in the KGB. Me – in the case of fellow student Volodia Roketskyi (member of the national-patriotic organisation “Kameniar”, poet, self-publisher, was arrested on January 14, 1972. – Author), who by that time was no longer studying with me (he was expelled from the university in 1971 year for the fact that on the anniversary of Shevchenko’s reburial, he read Danylo Kulyniak’s poem “The forest is being cut down” near his monument in Kyiv. – Author). And the father – in the case of Ivan Kovalenko. Mom was very scared. And I remember my father burning part of some records here in the garden. And he hid some more in the attic of the house. Probably then he also burned the second copy of “The 33rd year” manuscript, of which there were two.”

Lavro Lavrovych, who was 73 years old and had been waiting for arrest for long, thought they would come for him too.

Why was the father lucky the second time? Perhaps the mass of samizdat that was then quietly published, in its sharpness and content, was much more relevant for the then system than the work of my father. Or maybe they had plans for someone specific… Who knows, but for the second time, he was spared trouble by some miracle.”

…Lavro Nechyporenko, creating his notes, dreamt: “Maybe someday someone will read it.”

Today, the manuscript has been published, and everyone can pick up the newly printed book and live through that tragic year of 1933 with Lavro Nechyporenko.

Lina TESLENKO,

National Museum of Holodomor-Genocide

Source – Novynarnia