“I was little, exhausted, with swollen legs”: memories of an eyewitness to the Holodomor

This tragedy has no statute of limitations, and Ukrainians still feel the consequences of the Holodomor. The Marie Claire Ukraine magazine team decided to publish an interview in which the eyewitness of this tragedy, Ms Vaclava Stankevych (maiden name Kosminska), tells in detail about the horror that our country experienced in the 1930s. We decided not to publish these materials on the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holodomors since the memory of Stalin’s terror should not be limited to anniversary dates.

In 1932 and 1933, a catastrophic famine gripped Soviet Ukraine, caused by the deliberate actions of the leadership of the Soviet Union led by Stalin. Having announced a course of complete collectivization at the end of the 1920s, Kremlin leaders encountered resistance from the Ukrainian peasantry.

It is known about almost 4,000 mass demonstrations against collectivization, predatory taxation policy and Bolshevik terror that swept across Ukraine at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s. Well aware of the danger of riots and uprisings and not wanting to lose Ukraine, the Kremlin resorted to brutal actions. And under the guise of giving bread to the state, it began to implement its destructive plan. For Ukraine, an unrealistic grain procurement plan was established in advance – 356 million poods. When it couldn’t be implemented, the complete withdrawal of all grain stocks from the population and the confiscation of other food and property under the guise of fines for non-fulfilment of the plan began.

Armed tow brigades entered peasant yards and took away all edible food: potatoes, beets, beans, and peas, and they also took away livestock. At the same time, the regime blocked all ways of salvation — Ukrainians were forbidden to leave for cities, Russia, Belarus, and other countries in search of food. As a result of the massive man-made famine, which later became known as the “Holodomor” and was recognised as the genocide of the Ukrainian people, millions of people were exterminated on the territory of Ukraine.

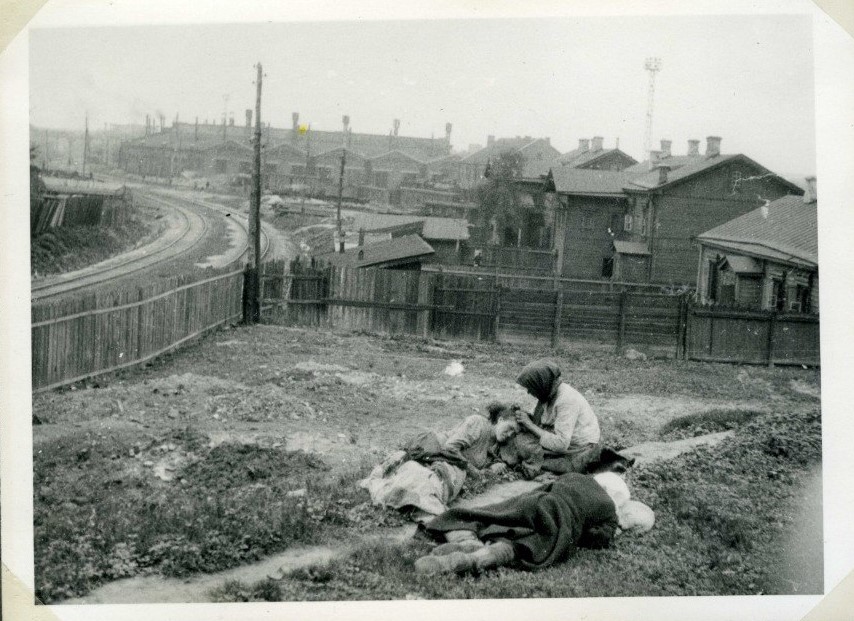

Doomed to death by starvation. Photo by Alexander Wienerberger.

“I want to tell you about what is still in my heart.”

The interview was recorded in January 2008. At the time of the recording, Ms Vatslava Stankevych was 84 years old. It was then that she turned to journalist Yadviha Yarova with a request to record her story.

“I am an old and sick woman, only the Lord God knows how long I have left to live. That is why I want to tell you about what is still in my heart.”

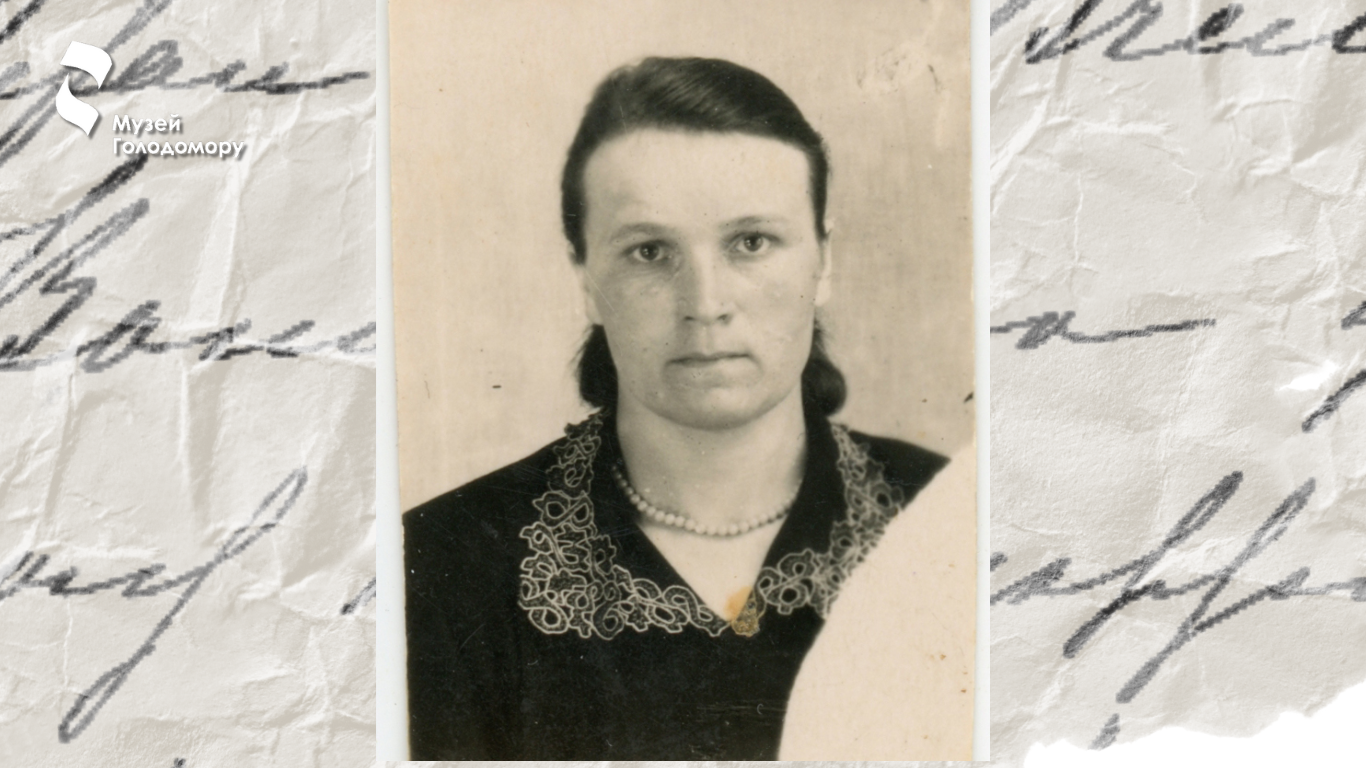

Vatslava Stankevych. 23 years old.

Vatslava’s father, Yuzef Kosminskyi, came from the ancient noble Kuzminskyi family of Yastrubets coat of arms. In the heraldry of Nesetsky, it is reported that the family originates from Kuzminб and it was first mentioned in 1530. In the 19th century, the Kuzminskyi family underwent declassification of the gentry, which forced the family to change its surname to Kosminsky. After the deprivation of rights, the family settled in Vinnytsia in the village of Hnativka and later moved to Sloboda-Kustovetska, where Ms Vatslava was born.

“My mother, Adele and father, Yuzef Kosminsky, had four children. Two died in childhood. Only my brother Vincent and I remained alive. “Once upon a time, the village of Sloboda Kustovetska in the Vinnytsia region was called Chechelivka – after the landlord Chechel’s last name,” Ms Vatslava recalled.

“I remember collectivization with horror. The life of a hardworking, friendly family turned into hell.”

Collectivization, the unification of private peasant farms into collective farms, was started by the leadership of the USSR in 1928. There, at the top, it seemed that by working together, the peasants would show better farming results. But for the Ukrainian owner, land and private property were important part of life! In order to join a collective farm, it was necessary to give not only land to public use but also horses, livestock, equipment and even farm buildings – barns and stables.

Those who had nothing, joined the collective farm willingly. But the wealthier peasants, who earned their wealth working hard, opposed this. And no promises of a bright communist future could convince them. That is why they began to forcefully drive people into collective farms. Those who disagreed were strangled with exorbitant taxes. And especially stubborn ones were made “class enemies” and began to be exterminated as “kulaks”. All their property was taken from them and they were deported to Siberia with whole families or sentenced to the highest degree of punishment – execution.

A dekulakized family near their house in the village. Udachne, Donetsk region, 1930s. Photo by Marko Zalizniak.

“I was six years old when collectivization began. I remember this period of my life with horror. The life of a hard-working, friendly family turned into hell. My dad had a horse that everyone loved and a milk cow. All property and livestock were taken to the collective farm. In the village, houses were dismantled for building materials and brought to the collective farm building on carts. There was no place to keep the cattle, so they took it home in the evening and returned it in the morning. I am 84 years old, but I remember all the events well. Two local Komsomol members took everything they could from people: grain, seeds, and even pickled apples from barrels. They pierced furniture and clothes with sharp picks, looking for gold.”

“The sister of the head of the village, Ms Maria, with two sons, lived opposite us. In order to speed up the sister’s entry into the collective farm, the headman broke the doors and windows in the house, and the weather outside was frosty and snowy. In order not to freeze, Ms Maria covered the windows with straw and the door with blankets. Unable to endure such a life, she and one of her sons died. Only Vania remained, who moved to live with the same orphan as himself. Soon, his parents’ hut was dismantled for building materials. They destroyed village houses until they built a store, a farm, and a stable. The stable was huge, and two guards worked there. Our family was left without a means of livelihood. We were happy that, at least, they did not take the chickens from us but the joy was short-lived as all the chickens were stolen from us at night.”

Vatslava Stankevych. 45 years old.

The policy of collectivization in Ukraine failed. Peasants left the collective farms en masse, took their property and raised numerous uprisings against the Soviet authorities. To destroy the resistance of the Ukrainian population, the Soviet regime, on the initiative of Joseph Stalin, issued several repressive resolutions.

“Farmers’ whole families died, corpses lay in houses for a long time”

On August 7, 1932, a resolution was adopted, popularly known as the “law oo five ears of grain.” According to this document, the state punished starving farmers for collecting crop residues in the field with imprisonment for ten years or execution.

In order to allegedly implement the plan, fines in kind were introduced by the resolution of the Council of People’s Commissariat of the USSR, “On measures to increase grain procurement,” dated November 20, 1932. They actually legalized an unprecedented robbery of the farmers, during which all food was completely confiscated. Special groups of people were organized to search the population and collect grain. Such searches were accompanied by terror and abuse of people.

Dekulakization. All property is being taken from families. Photo by Marko Zalizniak.

Soon, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CP(b) adopted a resolution that introduced a specific repressive regime for villages that did not fulfil the plan – “black boards”. Listing on “black boards” meant a physical food blockade of entire districts: total seizure of food, prohibition of trade and transportation of goods, prohibition of farmers leaving and surrounding the settlement with military units, GPU, and militia. Such a repressive regime was applied only in Ukraine and the Kuban, that is, in places where Ukrainians lived compactly.

The directive of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR dated January 22, 1933, prohibited the departure of farmers from Ukraine. In this way, Ukrainians were blocked within the territory of the famine, which condemned them to a martyr’s death by starvation. The calculation was obvious: hungry people no longer thought about protests and riots but only about survival…

“The terrible year 1933 came. Our mother would go to work every day with swollen legs from hunger to get 400 grams of flour. She added lupins, skimmed milk, which my father’s sister used to bring us, and baked cakes from this dough, which were called “polovyanyky”. She took such a cake with her to work. She tied it to the waist of her skirt so that it wouldn’t be stolen. Soon the children’s legs began to swell. Seeing no other way out, our father forced the children to go to the collective farm to work too.”

Children collecting frozen potatoes in the field. 1933 year. Photo by Marko Zalizniak.

“I was 9 years old, my brother was 12. From the products, we took half of the “polovyanyk” and skimmed milk. With this, we tried to stop the terrible hunger. Children from two neighbouring villages worked in the field. They walked in a row and pulled out weeds. Young plants were put in a pile, the thick skin was torn from the old ones and the soft middle was eaten. At the end of the working day, the children were given 200 grams of bread and a bowl of boiled “hychka” (beet stalks). Thickened beet sprouts were also pulled out in the field, beet stalks were cut and boiled in salt water. I was small, exhausted, with swollen legs, but I could not eat boiled “hychka”. The overseer who brought the food would sometimes give me a fish head or tail… One day I remember waiting for dinner and passing out from hunger. When I came to my senses, my bread was gone. A woman came to the table where we were eating and ate handfuls of salt that was on the table in bowls.

Farmers’ whole families died, and corpses lay in houses for a long time. The dead were piled up and thrown into a communal pit dug outside the village. The grain ripened in the fields, but the people were not given a single ear of grain. Sometimes, collective farm workers were given semi-raw grain, not fully cooked. Such food did not nourish the body because it was not digested.”

“Hungry children who were hiding in the cemetery would raid our garden”

To survive, hungry people ate everything that was non-toxic to the body. These were often burdocks, nettles and various weeds, there were no cats and dogs in the villages, as well as birds – sparrows, crows and storks. People hunted gophers, snakes and turtles. Children, who were the first victims of the Holodomor, especially suffered from such a “ration”.

“Behind our plot there was a cemetery where hungry children who raided our garden were hiding. As soon as the potatoes flowers bloomed, the children pulled them out in search of potatoes.”

Those people who managed to bury some supplies in the ground in advance so that they would not be taken away had a better chance of survival. But they also ended sooner or later. It was especially hard in the winter and spring as there were no plants, rodents or birds. People ate the bark of trees, rubbed peeled corn cobs, boiled leather goods… In April, everything started to sprout, but the green sprouts did not contain enough proteins and carbohydrates. People continued to swell from hunger. Therefore, April 1933 was popularly nicknamed Pukhnuten (English meaning: “Swollen”) and May – Kaputen (English meaning: “Kaputt”).

“Easter was coming. There were a dozen potatoes, some sauerkraut and wheat flour in the hut. We were waiting for the festive dinner. Mom mixed all the ingredients and baked one platska (pancake) for the children. Dad asked the collective farm women for two baskets of eggs to sell in the city and buy bread with the earned money. We had been waiting impatiently for dad for four days. Finally he returned with five loaves of bread. The children each received a large piece of bread and took one loaf to their aunt. She gave us Easter eggs for that.”

Blessing of Easter cakes. 1929. In a few years, the farmers will have neither Easter cakes nor bread. Photo by Marko Zalizniak.

“The father’s name was the first on the list of persons to be arrested”

The Great Terror is one of the largest campaigns of repression of citizens, launched in the USSR in 1937-1938 on the personal initiative of Joseph Stalin. The consequences of the communist terror in Ukraine were the destruction of the cultural and political elite, the destruction of national consciousness and mass fear among the population of the USSR authorities. The beginning of the Great Terror was the order of the NKVD of the USSR “On the repression of former kulaks, criminal criminals and other anti-Soviet elements” of July 30, 1937, approved by the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks. However, the available documents of the NKVD show that mass repressions were prepared and thought out in advance, and the formal order was only the starting point.

A dead man on Kharkiv Street. Photo by Alexander Wienerberger.

During the period of the Great Terror on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR, according to historians, 198,918 people were sentenced, and about two-thirds were executed. The rest were sent to labour camps, from which a very small part of the convicts returned.

“The year 1936 came. Finally, the terrible famine in the past. Thank God, everyone survived. Our family bought a cow. However, the peace was short-lived. The period of repression began. We were Catholics and father’s name was first on the list of persons to be arrested. He was saved by the old man. He categorically did not agree to send my father out of the village as a good farmer, an intelligent and respected person.”

We have to record and preserve every memory

Terror and repression continued throughout the existence of the Soviet Union. All this time, the truth about the Holodomor was silenced and hidden. However, even after the autumn of the Soviet Empire in 1991, Russia, as the legal successor of the USSR, continued to deny the Holodomor and continues to do so to this day. Because all this time it never gave up the idea of destroying Ukraine as an independent democratic state. In 2014, it began to implement this intention, and in 2022, it began a full-scale invasion of the territory of Ukraine, committing a new genocide.

By returning the truth about the Holodomor, we must record and preserve every memory, every testimony about those terrible times. Regretfully, every year the number of eyewitnesses to that tragedy is decreasing. Vatslava Stankevych, the author of these memoirs, also passed away, but it is crucial that she left her confession about her experiences.

Consequently, we appeal to fellow journalists and Ukrainian mass media: in different years, you recorded the Holodomor witnesses, and prepared materials and stories about them. Please look in your archives – perhaps, there are still records with their bitter and painful memories. Please look through newspaper files, TV and radio broadcasts, find their testimonies and hand them over to the Holodomor Museum. Everything is important: working materials (transcripts), photos, audio and video recordings or materials that were prepared based on them. Let’s bring back our history and the names of the people who witnessed it! We will also transfer Vatslava Stankevych’s memories to the Museum.

Photo: Marko Zalizniak (from the archive of Volodymyr Havshchuk, grandson of the photographer), Alexander Wienerberger (from the collection of Samara Pierce, great-granddaughter of the photographer), Bohdan Poshyvaylo (scans of photos from the family archive)

The material was prepared in cooperation with the Holodomor Museum