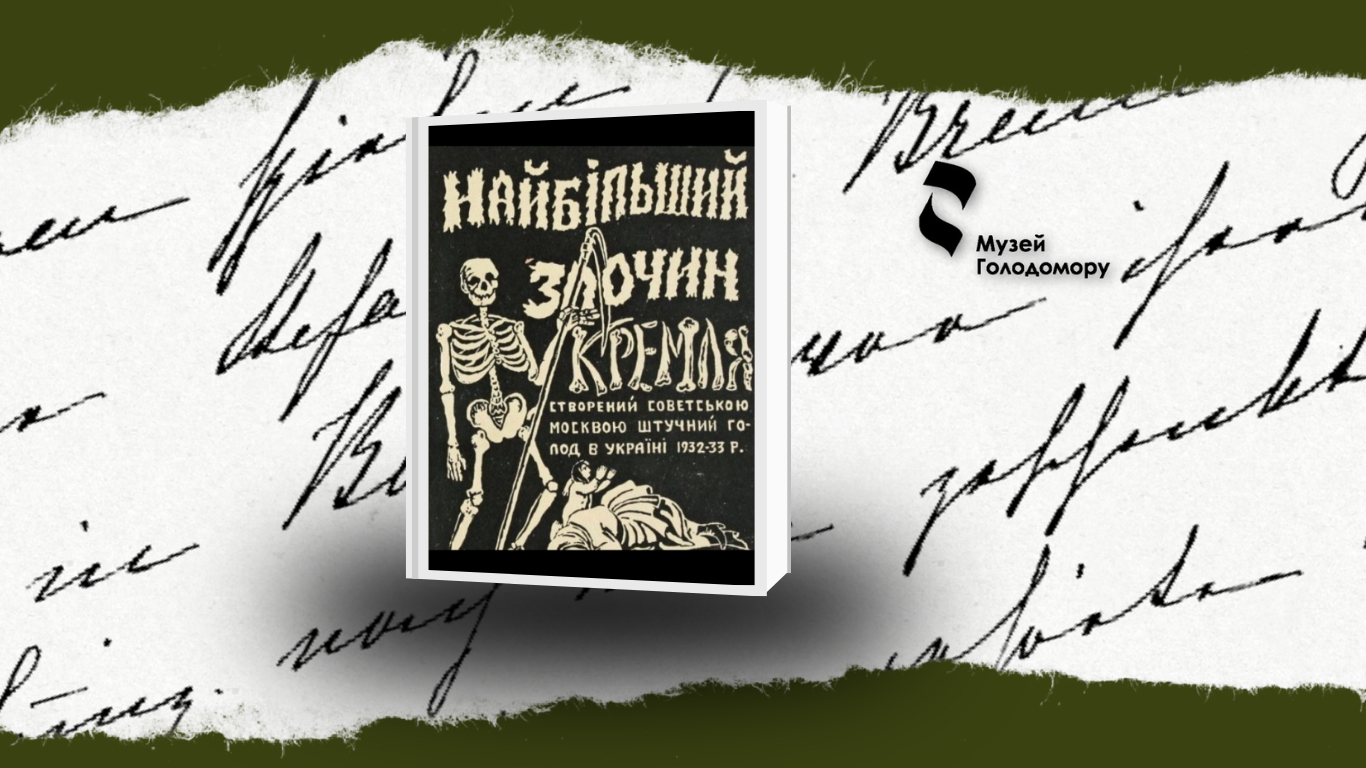

M. Verbytsky, “The Kremlin’s Greatest Crime: The Planned Artificial Famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933”

One of the first books to compile evidence on the Holodomor is M. Verbytsky’s “The Kremlin’s Greatest Crime: The Planned Artificial Famine in Ukraine, 1932–1933.” It was published in London in 1952, on the 20th anniversary of the Holodomor in Ukraine. Memories of ‘the immeasurable tragedy of our people’ were collected from members of the Democratic Association of Former Soviet Repressed Ukrainians in Great Britain who survived the Holodomor. ‘Western citizens must finally be shown, without fig leaves, this regime of the ‘country of victorious socialism’ in all its disgusting nakedness.We even believe that not only is it worth doing, but it is also our duty to do so. The thinking part of the Western world should read our book to understand finally who the world is dealing with today,” reads the foreword to the book.

From the memoirs of Taras Yakimenko, a peasant from the village of Budyshche in the Kyiv region (now Cherkasy):

“Norenko was a 40-year-old farmer, an exemplary landowner, with a wife and five children, and five acres of land. In the midst of the January frosts, a group of activists led by the Russian Commissioner Shlykov came to him. Upon entering the house, Shlykov said to the activists: ‘Everything down to the baked food!’ That is, take everything, including baked bread. No amount of crying and pleading from the family helped: they took everything movable and immovable, and drove them out of their own house with children aged 2 to 13. The children’s father did not take them out. Then Shlykov took them one by one, throwing them out of the window into the snow, and locked the house. An order was issued throughout the village: ‘Whoever lets them into their place will suffer the same fate tomorrow.’ The father and mother took the children and went to the forest near the village, where the father dug a cave in a ravine to settle down, even though this was not freedom. A couple of days later, the GPU took Hrytsko Norenko away. Soon, all the children died of hunger and cold. Lonely, exhausted, and grief-stricken, their mother left the cave, and her body was found lying face down on the ice-covered river. Such was the end of the entire family of this honourable, honest farmer… What for? How many such families were destroyed in Ukraine? “You know their names, Lord…”

From the memoirs of peasant R. Suslyk from the village of Syverynivka, near Zinkiv, Poltava region:

“In late autumn 1932, several dozen people armed with bayonets and probes arrived at the Severynivka farmstead from the neighbouring Hrynskyi district. This rabble split into groups, each led by a trusted ‘thousandman.’ They went from yard to yard, poking around the courtyards and gardens, tapping on the floors and stoves, and if they found anything suspicious, they broke through the stove, hammered on the walls, dug up the floor, and so on. First of all, they searched and checked what food had been cooked, and what ingredients had been used, as this served as proof that the collective farmers had food. As the brigade moved forward, carts became increasingly full of pots, jugs, bags, and boxes containing grain, millet, beans, peas, corn, flour, and hand mills of various designs.

These ‘successes’ did not satisfy the ‘party and government,’ and they did not leave the population in peace until spring. Every two weeks, teams of activists visited Severynivka and all the villages and hamlets in the district. It is interesting to note that village activists were gathered and sent to unfamiliar areas where they had no relatives or acquaintances and where they could more ruthlessly carry out this ‘state work’. The searches gave only a few kilograms, but the authorities achieved their despicable goal: to keep the population in constant fear, fear that the food they had managed to hide or get could be taken away at any moment. This insidious calculation by the authorities pushed people to consume food quickly, and led them to certain starvation. People had to cook and eat at night, and keep their stoves cold and empty during the day.”

You can download the book on the website of the Institute of History of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.