Silver Spoons Were Exchanged for Food: The Story of Marfa Kovalenko

We continue the series of stories about the Holodomor witnesses recorded in the framework of the project “Holodomor: Mosaics of History”, which is implemented jointly with the NGO “Ukrainer” with the support of the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.

Marfa Kovalenko was six years old when the Holodomor began. Her family survived thanks to dishes from a set that was once given to their grandfather by the landowners. These items were exchanged for a meager amount of food in the torgsin shops, so there were no Holodomor victims in the Kovalenko family.

Kostiantyniv. Marfa’s family

The village of Kostiantyniv is located on the right bank of the river Sula in Sumy region. Now it is almost extinct — there are only a few inhabited yards. However, in the 17th century. it was a wealthy trading town, which in the 19th century became the property of the Counts Golovkin, and then — the Counts Khvoshchynsky. Marfa’s grandfather, Yakym Kovalenko, workerd in their estate, and this later saved his family from starvation.

Photo: Kovalenko family. On the bottom to the right — Yakym Kovalenko, Marfa’s grandfather. From the archive of Kovalenko family.

Marfa Kovalenko was born in 1926 in the a family of paramedics. Her father, Danylo Kovalenko, worked at the hospital in the neighboring village of Korovyntsi, which Count Golovkin had once transported from Kostiantyniv. In the hospital, in addition to the paramedics, there were other specialists who were able to visit the seriously ill and even perform operations. Nearby, there was a building for doctors and their families, where Marfa’s parents lived. However, they often visited their daughter, who stayed with her grandfather in Kostiantyniv.

Photo: Certified paramedics of Nedryhailiv district. Second person from the left in the lower row is Danylo Kovalenko. 1950. From the archive of Kovalenko family.

Marfa’s parents had two other children — Oleksii, who had died from scarlet fever before she was born, and Fedir. Her father’s younger sister died of scarlet fever, too. Marfa also had scarlatina when she was very young, but she survived.

“When my brother came, he was not allowed into the house. As I started to recover, we spoke through the window. He was outside, and I was in the house by the window — this was how we would talk. At the same time, he will either go to Korovyntsi or spend the night at the neighbors, and in the morning he will go to school in Korovyntsi with the children.”

When the collectivization and dekulakization began in Ukraine, Marfa’s family also suffered, although their father worked in a hospital.

“We didn’t have large garden, so they cut off my father’s garden. He was not a collective farmer, so they left fifteen hundredths. This is what was under the yard. And the father said: “You can take away the garden that is planted, but leave the garden under the mountain for me.” I could go to our garden by a path here, and there the collective farm planted in our garden, my grandfather’s.”

Brigades, searhcing sticks, and broken dishes

What Marfa Kovalenko remembered the most was the winter of 1932–1933.

“There were potatoes in the cellar, beets, cabbage in a tub, a cucumber there, that’s what we had.”

Brigades with metal sticks were going to the village. These sticks were called “shchupy”; they searched for grain hidden in the ground with them. Cooked meals were also taken away.

“They came in, looked into the oven, took everything out and poured it out. Even pots were thrown and broken. The dishes were only made of clay then.”

Such a brigade also came to the Kovalenkos’ yard. That day little Marfa stayed at home with her grandfather:

“In the winter of the 32nd or 33rd, a brigade came to us. The dog barks, and it’s winter, it’s cold. While my grandfather was dressing me, they went to the yard. Everyone is local, from Konstiantyniv. I knew one thing: a man with red hair, his name was Vasyl. “Tie the dog,” they say to my grandpa. And the dog was near the barn, the cow was in the barn. Well, they needed to enter a barn. They went into the barn, untied the cow and took it away. And the same red-haired Vasyl, a nearby neighbor, pushed my grandfather. Grandfather fell. And so I started screaming.”

Marfa’s father, as he was a paramedic and not a collective farmer, went to Nedryhailiv to the chief doctor and tried to return his cow, but refused to take someone else’s:

“If they bring a cow that was ours, let them put it in the barn. If they bring a cow that has been taken from a man, a woman, who was four or five children, do not bring me that cow.”

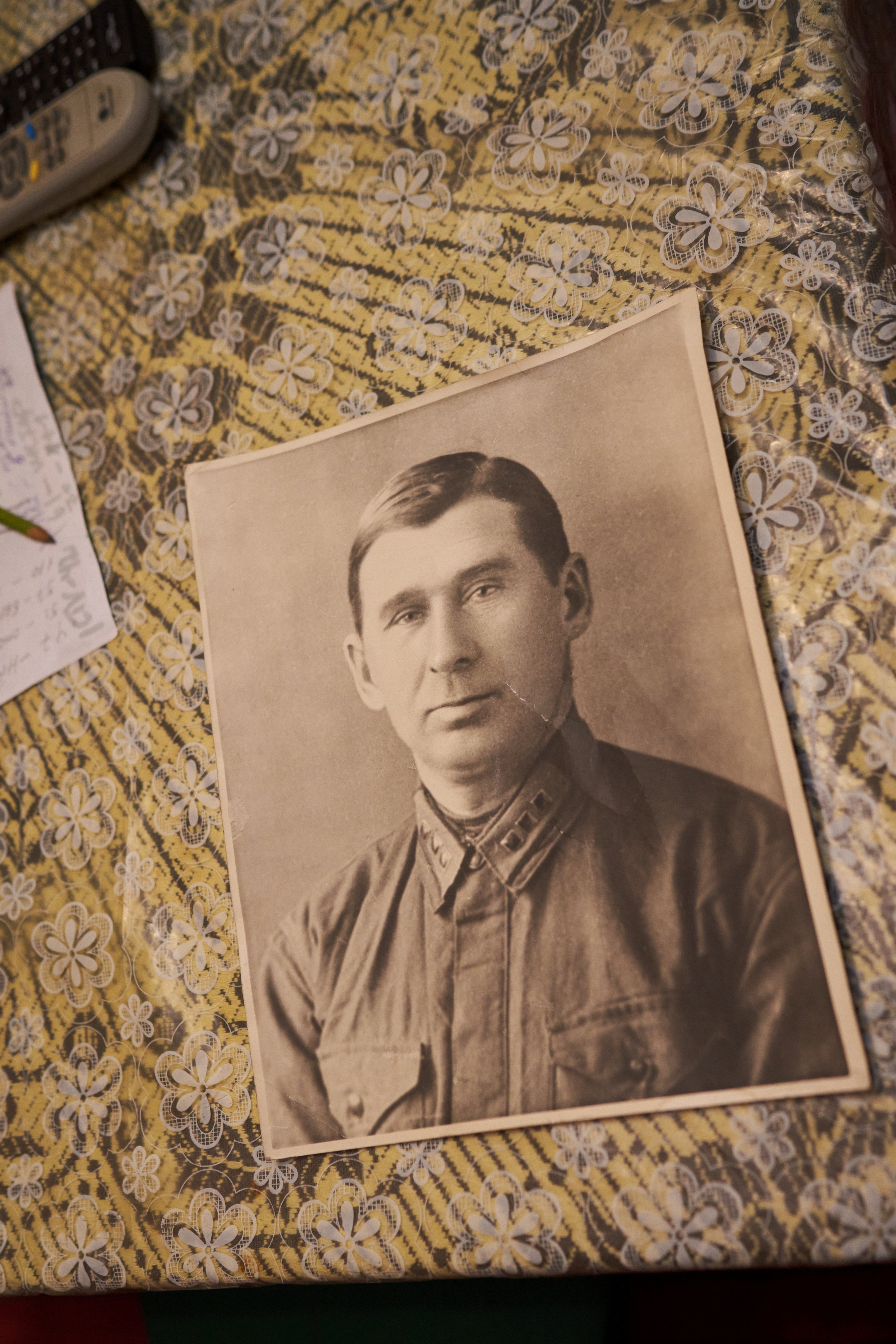

Photo: Danylo Kovalenko, Marfa’s father. From the archive of Kovalenko family.

They promised him that the cow would be brought back, but they never returned the cattle back.

“And so we stayed for the spring. We had beets, potatoes, garden, dry apples. There was a sugar factory in Terny, so there were also sugar beet seeds.”

The farmers did not resist the confiscations, since they were afraid of physical violence.

To survive, people prepared “solodukha” (a liquid dish of sugar beet) for dinner and baked cakes from leaves:

“They cooked sugar beets. Peeled, cut into pieces — in four or into halves (what size beets are) and boiled them. Then, as they were cooked, they cut them into such squares, and added to cucumbers or cabbage. There was no more bread. People baked “herbyky” (cakes from leaves). Those who had a cow could cook that cake from milk. My mother did not bake them because there was no milk.”

In the spring there was nothing to plant on the gardens, so potatoes planted from their husks. Sometimes children dug up unripe potatoes from the ground, ate them and died of poisoning.

The farmers, who were still alive, did not have the strength to bury the dead. The village council provided a cart that drove along the main street and collected the bodies, which were then buried in the cemetery in mass graves.

On August 7, 1932, the so-called “law on five ears of grain” was passed, which forbade farmers to gather ears of gran for themselves on collective farm fields — such actions were considered theft. The fields were guarded by patrolmen, who did not allow the farmers to “steal state property”. They made sure that hungry people did not cut the ears in the fields and did not pick them up after the harvest. The guards beat the children with a whip, Marfa recalls. Those who were lucky enough to gather a few ears of grain, boiled them or ground them into flour.

Photo: Museum employee Yuliia Kotsur together with Marfa Kovalenko look through the family archive of Kovalenko family. By Valentyn Kuzan.

With the beginning of collectivization, the millstones were confiscated and destroyed. In Konstantynivka, only a blacksmith had them, but not everyone was allowed to use them, because he was afraid that someone would report to the village council and the millstone would be confiscated:

“Only he was grinding for those on the board. Not everyone could grind: his relatives, acquaintances, friends. It turned out later.”

In September 1933, Marfa went to first grade with older children. The school was located right behind the house, in the former priest’s house. The class was large, more than thirty children. Then children of different ages, from seven to ten years old, went to the first grade. At school, children were not given food. Older brother Fedir assisted the family. He studied in Romny at the College of Agricultural Mechanization, where students were provided with food:

“My brother studied in Romny during the famine in 1933, and he would bring such a piece of bread to his mother on Saturday. And once I was the first to take it and ate it, and he cried: “I was bringing it for mom!”. Then the mother shared it between herself and us, and gave most of it to us.”

People often helped each other during the famine. Marfa remembers how she and her friend Sonia drove a cow from the pasture to aunt Anna from their village every day, and she gave the girls a mug of milk:

— I was not swallen. The girl and I drank two mugs, whatever they were, well, there were 300 or 200 grams of milk.

Sonia’s older brothers, Ivan and Borys, did not survive the famine. They were buried in an old cellar. Later, their grandmother died:

“The boys died, so their father took [the bodies] to the cellar, which was already destroyed. Somehow he covered them with gound. My grandfather and there another grandfather dug a hole to the depth of the knee near the cellar where the children were buried. And then the graves was built there.”

“Unnecessary things” of silver

During the 1918 revolution, Count Khvoshchynsky’s family left their family estate. Fleeing the Bolshevik government, they took with them everything they could. And what they could not, they distributed among the people who worked for them. This is how Marfa’s grandfather Yakym Kovalenko got a part of a silver set and utensils:

“The complete sets remained with tem, and where there was one spoon, or two forks, or something for children, the grandfather brought this. She said, “Take it, this is a gift for your boy.”

These things survived and saved Marfa’s family from death during the Holodomor.

“Our family was saved a lot during the famine due to what that lady gave us — ‘unnecessary things’ of silver. Two or three spoons; I still have a teaspoon, already broken, stainless steel knives with a silver block, a fork, and a dish for herring.”

Photo: Marfa Kovalenko holds the teaspoon from the landowners’ set, which was not exchanged for food during the Holodomor. By Valentyn Kuzan.

Items made of precious metals during the Holodomor could be exchanged in the torsin shops. In order not to die of starvation, people took all valuables, silver and gold, and exchanged them for food by low prices. However, sometimes this could save lives:

“In Romny, there was such shop, so called Torgsin. My grandfather took either a spoon or a fork, and went there. He brought a handfull or something, and already there the mother has made some kind of suop. We survived, no one in our family died.”

Marfa Kovalenko donated to the funds of our museum the dishes from this set which were not exchanged in the Torgsin for food — a silver spoon and a plate for herring.

Photo: Plate for herring Marfa Kovalenko donated to our museum. By Valentyn Kuzan.

Count Khvoshchynsky’s estate, farm buildings, and a tractor were transferred to the commune, which later united with the local collective farm. Soviet authorities also destrpyed the church of the community, turning it into a granary, where Marfa Kovalenko herself worked during World War II. This church was restored in 2007-2009 and is now one of the most famous architectural monuments in the region.

During the Holodomor in Kostiantyniv, according to Marfa, most residents survived due to the mutual assistance. The farmers did not lose their humanity and shared the latter with others even when they themselves had nothing to eat.