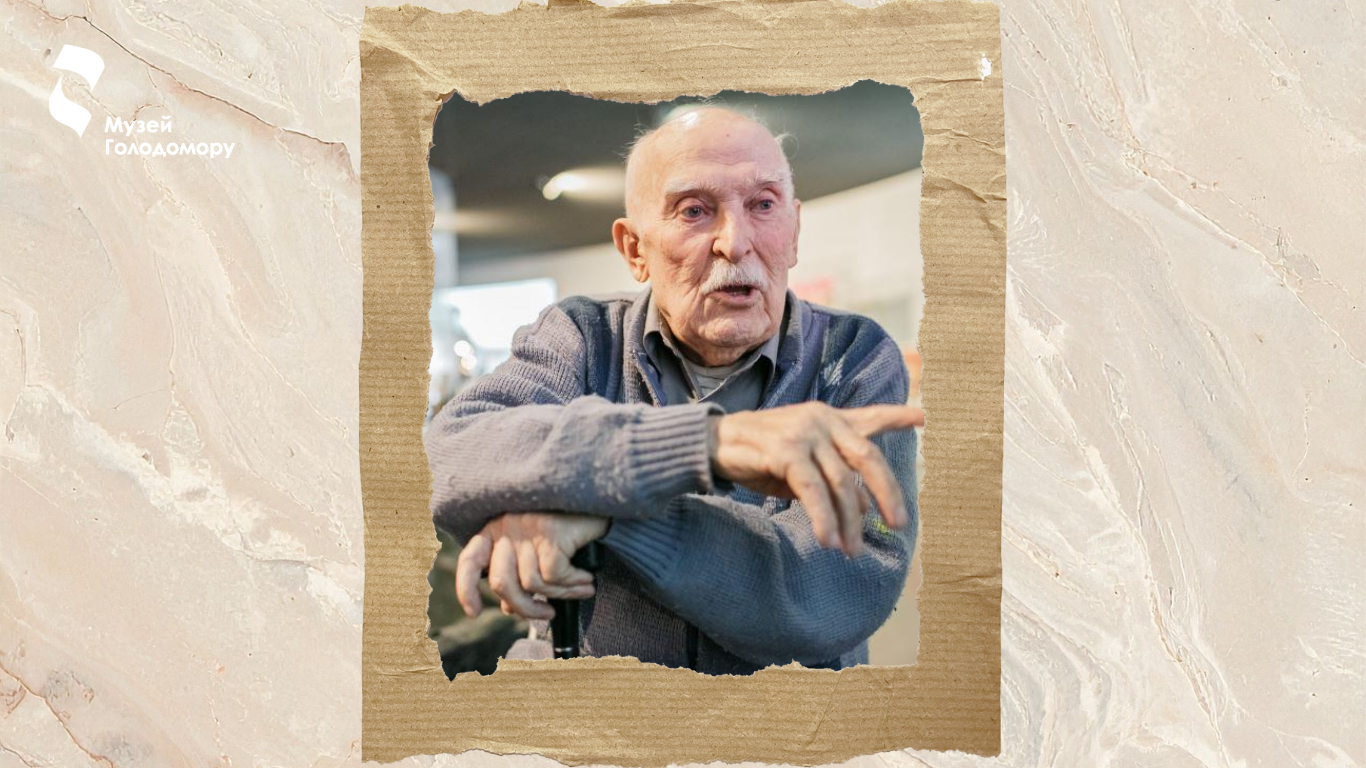

Centennial of the birth of Mykola Pavlovych Onyshchenko, witness to the Holodomor

16 December marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Mykola Pavlovych Onyshchenko, a Holodomor witness, member of the Supervisory Board of the International Charitable Foundation of the Holodomor Museum, and a close friend of our museum. “The Holodomor crippled our Ukrainian nation. The creation of the Holodomor Museum is the first step towards the restoration of the nation,” he emphasised. After all, the genocide by starvation became the point of no return that changed Ukrainians and Ukraine forever.

He was seven when the Holodomor began. His family lived in the small village of Roza in the Berdiansk region. His father worked as a stevedore at the port and received rations, which helped the family survive.

“I remember the village and our people before collectivisation. People were completely different. In our small village, there were three choirs, and they would sing in the evenings when the weather was warm. They would go to work singing. My mother used to sing all the time, no matter what she was doing. After the Holodomor, both people and Ukraine changed. They stopped singing. After the Holodomor, the village and the people were no longer the same.”

He called the period before collectivisation ‘the best years of his life.’ “The yard was full of all sorts of animals: turkeys, which I was afraid of, and geese, and chickens, and sheep, and a horse, you name it. There was a huge cherry orchard and grapevines. I clearly remember climbing into my grandfather’s attic as a child. In that attic, under the thatched roof, hams were hanging in a row, bowls filled with lard, sausages, bacon in boxes, and honey in bowls. It was a miracle. And my grandfather had it all. When collectivisation began, I saw an empty yard: no horses, no geese, no sheep, nothing. There weren’t even any cows. I remember my grandmother crying that our cow was dying in the collective farm. They tied her to a beam [because she could no longer stand]. Grandmother picked grass and went to feed her.

Those people, deprived of their land and livestock, became beggars. What does it mean to take away a peasant’s land? They left with nothing. And then they began to take away the bread from these ragged beggars. You cannot imagine the people of that time. And no film can show it. Where can you find such people: thin, scary, in rags. People’s clothes were so worn that it was impossible to tell what the original fabric had been. It was patch upon patch on shirts, trousers, and shoes. The entire village was full of beggars. Bread was taken from the hungry. Everyone was terrified.

I remember my mother running around with a basket containing about a bucket and a half of corn. There was a barrel of cucumbers standing by the stove. My mother brought the bucket. She poured the pickle juice out of the barrel. Then she poured out the cucumbers, stuffed the bag of corn into the barrel, put the cucumbers on top, covered them with slices of bread and stones, and then three inspectors appeared. The oldest one approached my mother and said, ‘Where is the grain?’ ‘We don’t have any grain.’ He said to the other two, ‘Go to the garden, to the attic, and look for it.’ They found nothing. Then he looked at the barrel: ‘Why are your cucumbers dry?’ He looked, and there was a sack between the cucumbers. He reached in, pulled out the sack, and the cucumbers and stones fell out. He threw the bag over his shoulder and left the house. My mother grabbed the bag and started screaming and wailing. We grabbed her skirt, and the man pulled us out into the yard. He let go of us. Two carts were standing there, and people were shouting. They drove away. Even the dogs hid. It was violence. Those who grew bread ended up without bread.

Hunger came to us, too, although we did not die of starvation. The people opposite us died of starvation. Those swollen, terrible beggars came, but there was nothing to give them. My mother told me not to leave the house because they would eat me. There were rumours that someone had already been caught and eaten somewhere. My father travelled from Berdiansk and was very afraid because people were being caught somewhere in the steppe. He was scared that they would catch him. We survived because my father worked.”

“We must remember the Holodomor, remember who is to blame for it, remember that all the misfortunes of Ukrainians came from the north, from the Russians,” Mykola Pavlovych emphasised. In 2014, the Russians brought trouble to Ukraine again: at the age of almost 90, Onyshchenko, who lived in Luhansk (before retiring, he was the chief engineer of Luhansk Locomotive Works and a lecturer at the Volodymyr Dahl East Ukrainian University), was forced to move to Kyiv with his wife and live out his days with friends. On 12 April 2021, he passed away at the age of 96. He was buried at Baikove Cemetery.

May you rest in peace, Mykola Pavlovych!