Iroida Vynnytska: One of our priorities was studying the history of the Holodomor in Canadian schools

Iroida Vynnytska is a researcher of the oral history of the Holodomor of Ukrainians in Canada, a member of the Ukrainian-Canadian Research and Documentation Center, and an active member of the Ukrainian diaspora. Having met the famous Holodomor researcher James Mace, she actively joined the work of the US Congressional Commission headed by him for the study of the Great Famine in Ukraine.

As part of the cooperation with the Mace Commission and the general work of preserving the memory of the Holodomor, Ms Iroida recorded dozens of hours of audio testimonies with people who survived the Stalinist genocide. The specific value of these records is that they were collected in time from people who were adults or teenagers at the time of the Holodomor and remembered the tragedy well in detail.

But even living far from the USSR, witnesses were still afraid to share their experiences openly, or they talked anonymously. After all, they were worried that their revelations could harm their relatives who remained in the “prison of nations”. We contacted Ms Iroida via video to learn more about her biography and work on collecting and preserving eyewitness accounts.

Iroida Vynnytska

Iroida Vynnytska (maiden name – Lebid) was born on February 17, 1933 in Matiiv village (current name – Lukiv) in Volyn. The future researcher spent her childhood in Vorokhta village in the Carpathians, where the family had its own boarding house, at the expense of which the family lived. However, the carefree childhood was interrupted by the Second World War. The family returned to Volyn. The Soviet and German occupation became a real test for Iroida and her parents.

“I only remember when I was a child that my mother did not let me go to school on some days, I did not understand the reason. Well, but then I found out. In the middle of the city there was a gallows where they executed insurgents, members of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, because at that time it was a very insurgent army in Volyn developed and insurgents ruled almost everywhere in the villages, so the Germans caught people and hung them on the gallows. And so those insurgents hung in the middle of the city for several days. Of course, my mother did not want to let me go to school, because to get to school I would have to cross that square,” Ms Iroida recalls the times of the Nazi occupation.

On January 15, 1944, the family moved to the Czech Republic and later to Germany in order not to fall into the hands of the Red Army. As Ms Iroida recalls, there was no feeling that they were going abroad forever – they thought it was temporary. Fortunately, the family managed to find themselves in the American occupation zone. Then there were camps for temporarily displaced persons (DP), where Ukrainian life was seething.

Ms Iroida fondly remembers studying at the Ukrainian gymnasium in Modržany near Prague (February-June 1944) and staying in the DP camps, which gave her new friends and knowledge. In particular, Natalia Polonska-Vasylenko was a history teacher at this school. PLAST was also active in the camps. However, for adults, life there was not so carefree: they did not understand how their future would turn out and were afraid of possible repatriation to the USSR.

On January 23, 1949, the Lebid family moved to Montreal, Canada. This marked a new stage of life for Iroida, who began studying at a Canadian school.

Later, Iroida Lebid entered the university, where after the first semester, she received a scholarship for free education: in all subjects, except for English, she had excellent grades. It was the difficulties with English that led to the fact that instead of the dream profession of a teacher, the girl chose a natural science speciality – bacteriology, on the advice of her teacher.

Even now, Ms Iroida bitterly remembers the words of the school principal, who convinced Iroida that she would never be able to learn English to the level that she would be able to work as a teacher. Thus, with her imprudent word, the teacher postponed Iroida’s dream of teaching for several years.

Later, Ms Iroida was still able to engage in teaching activities – she taught in public schools: Lively, Toronto and Kitchener (1956–1958 and 1964–1972), taught Ukrainian at the University of Waterloo (1971–1978), and in 1976 received a master’s degree Slavic Studies A significant conclusion for Ms Iroida was the importance of learning Ukrainian in childhood. Many adults who grew up in Ukrainian families in Canada regretted that parents did not consider it necessary to teach their children the Ukrainian language.

Iroida Vynnytska conducts a tour of the exhibition at the The Ukrainian Canadian Research & Documentation Centre. March 5, 1992. Source: UCRDC archive

Iroida Vynnytska remembers the words of her students: “Why didn’t mum and dad teach me Ukrainian when I was a child? And now it’s hard for me, I have many other subjects, but I want to know that language.”

The topic of the Holodomor was familiar to Iroida Vynnytska since childhood, as it circulated in the circles of the Ukrainian emigration, where these terrible events were constantly mentioned, and the memory of the innocent killed was honoured. Alfter moving to Toronto, Ms Iroida participated in rallies and other events of the Ukrainian diaspora dedicated to the Holodomor every year.

Ms Iroida’s work at the Multicultural History Society of Ontario inspired her to create an archive of the oral history of Holodomor witnesses. This direction was directly related to the activities of this organization, which studied the culture of various ethnic groups living in Canada.

Work in this institution gave impetus to Ms Iroida’s organization of the Archive of the Committee for the Study of Famine in Ukraine. In addition, she directly began recording new interviews with Canadian Ukrainians, primarily with those who survived the Holodomor.

Ms Iroida mentions attempts to obstruct the work of the Committee by the USSR Embassy in Canada:

“We have a document that came to us from the USSR embassy in Ottawa, as if we invented the Holodomor, that the committee was comprised of Nazis themselves… We laughed a lot because there were 7 people in the committee, three of whom came to Canada as minor boys, yes, that it was difficult for them to be Nazis, and others were born in Canada and fought in the Canadian Armed Forces against the Nazis. So we laughed at that letter from the embassy.”

In 1988, the Committee was renamed the Ukrainian-Canadian Research and Documentation Center. The institution activity expanded as the number of the Holodomor witnesses in the diaspora became fewer and fewer. Subsequently, the project “Children of Holodomor Witnesses” was launched. These interviews focused on knowledge about the Holodomor. It was important to understand how much this topic was mentioned or taboo in families.

James Mace’s speech at the “Holodomor in Ukraine 1932-1933. New Research Findings” conference at the University of Toronto. Toronto. September 30, 1990.

Source: UCRDC archive

While working at the Documentation Centre, Ms Iroida collaborated with prominent Holodomor researcher James Mace, who she met personally at the University of Toronto in 1990 at a Holodomor conference:

“He [James Mace — ed.] was one of the speakers, he spoke about his work in the Congressional Commission. Then I met him personally. But even before that, he had been collecting witness statements in America and wanted to spread [this activity — ed.] to Canada, so he approached the Documentation Centre and sent a staff member to record several interviews in Canada. Then he agreed that I would arrange for the recording of such interviews. And we, so to speak, collaborated with his project. We recorded 27 interviews that were included in his publication, the third volume about the Holodomor”.

Oral History Conference. In the first row, the second from the right is James Mace, the third from the right is Nataliya Dziubenko-Mace, and the fourth from the right is Iroida Vynnytska. Lviv. September 5–7, 1994. Source: archive of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences.

Thus, Ms Iroida directly joined the work of the US Congressional-Presidential Commission on the Study of the Great Famine in Ukraine in 1932-1933.

Also, at the conference in Toronto, Ms Iroida met Volodymyr Maniak, co-author of the memorial book “33rd: Famine”. Later, in September 1990, they had another meeting already in Kyiv. Then Iroida Vynnytska copied over a hundred letters that Holodomor witnesses sent to Volodymyr Maniak. These copies were added to the funds of the Documentation Centre.

Another important direction of Iroida Vinnytska’s work was introducing Holodomor history into the Canadian school curriculum. The well-known Ukrainian historian Orest Subtelny also joined this. Douglas Tottle, under whose name the book “Fraud, hunger and fascism: the myth of genocide in Ukraine from Hitler to Harvard” was published, actively opposed such an initiative.

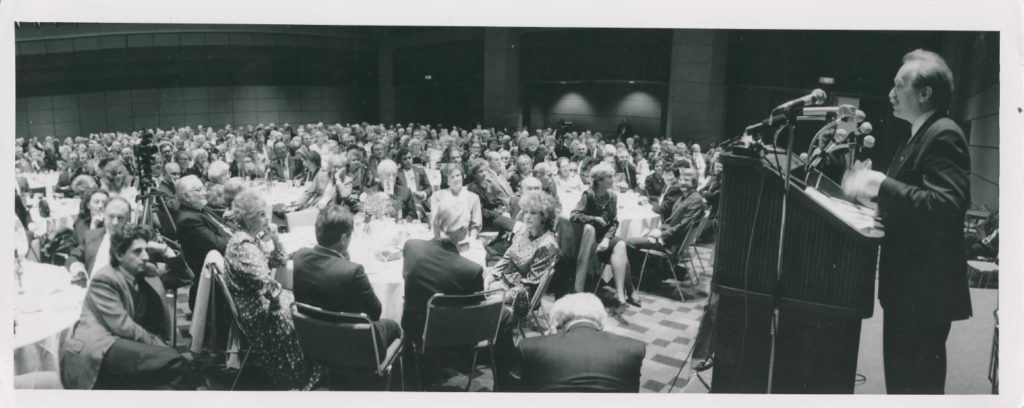

Vyacheslav Chornovil’s speech at the banquet on the occasion of the end of the scientific conference “Holodomor in Ukraine 1932-1933. New Research Findings” (“The Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine. New research findings) at the University of Toronto. Toronto. September 30, 1990. Source: UCRDC archive.

As soon as Ukraine gained independence in 1991, it was possible to add the history of the Holodomor to the Canadian high school curriculum: “It was one of our most crucial priorities that students study the Holodomor in high school…we were able to introduce the Holodomor into the school system,” Ms Iroida emphasizes.

After Ukraine gained independence, Iroida Vynnytska managed to share her own experience of oral history research with students-historians and folklorists who studied at Ivan Franko Lviv State University named. She also edited the unique collections “Unusual Destinies of Ordinary Women: Oral History of the 20th Century” in Ukrainian (2013) and English (2022). Currently, the woman lives in Toronto and continues to take an active part in the life of the Ukrainian diaspora and the Documentation Centre.

Iroida Vynnytska giving a lecture about the Holodomor to the students of the school named after Tsiopa Paliiv. November 17, 2007

Iroida Vynnytska calls her research “live history”. In the whirlpool of turbulent events, when the unique human experience is often lost against the background of geopolitics — life in the conditions of different political systems, wars and genocides — recording the behaviour patterns of a specific person at a specific moment makes history much closer and clearer.

Mykhailo KOSTIV,

Head of Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Research Department

of the National Museum of the Holodomor-genocide, candidate of historical sciences

Source- Istorychna Pravda