Surviving in the “collective farm paradise”: voices of living Holodomor witnesses

Dmytro Vyniarskyi. Photo: Holodomor Museum

Dmytro Viniarsky was 9 when the communists staged the Holodomor, a genocidal famine though to have taken the lives of at least 4 million Ukrainians. In his story collected by Kyiv’s Holodomor Museum, he tells about how their family survived by cooking gophers, and how the Soviet activists managed to confiscate absolutely everything edible with sharpened metal sticks.

The Holodomor, an artificial famine staged by the communist totalitarian regime in 1932-1933, took the lives of millions of Ukrainians. We will probably never know the real number, as recording the real number of the deceased was prohibited. So was writing “hunger” as the reason for their death.

The Holodomor Museum, located in Kyiv, is conducting large-scale expeditions throughout Ukraine as part of the project “Holodomor: a mosaic of history. Unknown pages,” searching for Holodomor witnesses and still-unknown places of mass burial of the victims of this genocide.

Witnesses who were children at the time of the tragedy tell incredible stories about what they went through and how they managed to survive.

In our first article in the series of publications within the media partnership of the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide and Euromaidan Press, we tell the story of Dmytro Viniarsky, whose family barely survived the forced collectivization and Holodomor conducted by the Soviets in the 1930s.

Dmytro Vyniarskyi was born in Chumaky village, in Sicheslav region (currently Dnipropetrovsk Oblast), founded in the early 18th century on the territories of the Zaporozhzhian Host, the cossack state that challenged the authority of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The citizens of these lands, the descendants of Cossacks, were known for their love of freedom. We see it from the story of our hero as well. Even under the pressure of the communist totalitarian regime, he always aimed at staying a free person.

Dmytro’s Family: growing up in the years of the New Economic Policy (NEP)

When Dmytro was just a baby, his family moved to the neighboring village of Chervonyi Yar. When the USSR temporarily introduced market economy elements in 1922-30, the years of NEP (New Economic Policy), the Vyniarskyi family was given a little plot of land there, and they built a house.

His father Denys Vyniarskyi met marshal Georgiy Zhukov, who later became known for his ruthlessness during WWII, during his service in the army. Already back then, the savage temper of this future military leader started to show itself: “When somebody was even a little guilty of something, he punched, punched them in their face.”

Dmytro Vyniarskyi’s father recalled that Zhukov taught him that one must love freedom.

Dmytro Vynirskyi holds the portrait of his father, Denys Vyniarskyi, taken in time of his father’s service in the army. Photo: Holodomor museum

After the father’s demobilization, the family was given a little plot of land, and in few years, they could create a small household:

“People started to live well when they got rich in the NEP times. I say, my father had nothing. He was given a piece of land, two desiatynas for each family member, and people started to come into some money, they started to prosper and that’s why they were ‘dekurkulized’. The ones that had a big family, a good piece of land, and the harvest was quite good. I remember how my father bought a horse, the horse was of a Mongolian breed, a little one, we called it Chubka… Then, the second year, my father bought a troiak. The troiak is a plow with three plowshares.”

In the first years of keeping a household, Denys Vyniarskyi collaborated with his neighbors who also cultivated the land: “Father’s horse and neighbor’s horse were hitched together.”

This form of collaboration, when a field and equipment remained in private possession, was natural for the Ukrainian farms, in particular, in southern Ukraine, where it became popular. In contrast to kolkhozes , collective farms which were violently forced by the сommunist totalitarian regime, the Ukrainians took positively common cooperation or mutual help that allowed keeping a household more effectively.

However, the economic development of Ukraine, where the central role was given to the successful households, was not in the plan of the Soviet occupants. Already from the end of the 1920s, the liberalism of NEP was brought to an end. Here came the time of total control over all the sectors of life.

One of the most striking processes that led to the violent destruction of the traditional standards of life was forced collectivization, which was the first sign of future upheavals for millions of Ukrainian families.

Collectivization

These significant processes of the first part of the 20th century influenced the family of our hero as well. When the collectivization began, the father of the family refused to join the kolkhoz and give everything he earned away voluntarily. Dmytro Vyniarskyi says,

“My father didn’t want to leave his NEP… And then they started to drive people into kolkhoz. If you don’t want to go there, you will be sent away from Ukraine, that’s how they called it… they deported people to frighten them, to make them go to the kolkhoz… Everything, everything was taken away from us to the kolkhoz.”

Everyone who didn’t want to accept the conditions of the communist totalitarian regime were called kurkuls, aka “curmudgeon.” This definition had a political, not economic meaning. Many “kurkuls” were deported to the distant regions of the USSR, in particular to Siberia and the Far East where they lived in the status of special settlers in the correctional labor camps:

“They deported, they expelled people to Siberia… to the Far East, Siberia… They deported people to frighten them.”

Moreover, Ukrainians in Ukrainian villages were imposed with the high quotas of bread they needed to give as independent farmers. This way, all the stocks of food were gradually pumped out:

“If you didn’t give the necessary amount of bread, you were imposed with a higher quota, and more, until you had nothing. That’s how the famine came…”

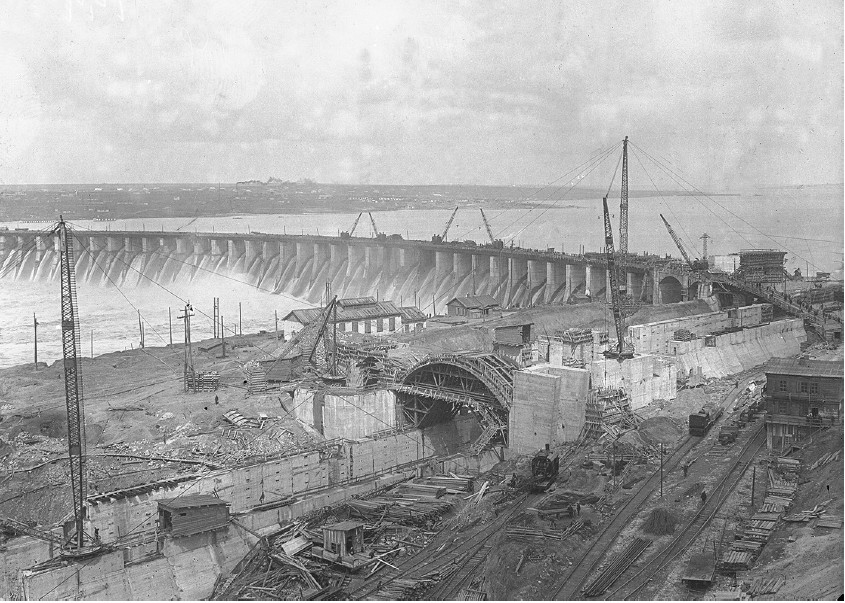

The great hydroelectric construction

Unwilling to end up in the slavery of the kolkhoz, the father went to work on Dniprobud, one of the largest Soviet industrial projects — constructing a cascade of hydroelectric stations on Ukraine’s largest river, the Dnipro.

“My mother was in the kolkhoz, but father didn’t want to, so he went to earn money to the Dniprobud.”

The labor was harder than slavery, but it was still difficult to get a job in the enterprise. Despite everything, it was one of the chances to receive a minimal food ration that was giving a possibility to survive 1932 and 1933, the most terrible years for all Ukrainians.

At the end of the 1920s and especially at the beginning of the 1930s, there was a massive exodus of population from the village to the industrial sites where one could receive at least some material security. Until the end of the 1930s, around 40-50 million villagers ran away from collectivization. Half of them were from Ukraine and the North Caucasus.

These huge numbers are a testimony of the chaos and insecurity that reigned in the “Soviet paradise.” Millions of people were forced to leave their homes. Some were marked as “kurkuls” and deported to far Siberia, some, saving themselves from hungry death, were forced to leave their family in hope of survival.

To restrain this process, in December 1933, a special regulation implemented passportization. Since then, one could not get a job in the city or even visit urban areas without an internal passport or residence permit. However, it were cities and industrial sites that provided asylum for village runaways. This happened to our hero’s father. At Dniprobud, he was given bread and a small food ration.

A general view of the DniproHES dam. The source: GS Pshenychnyi State Film and Photo Archive of Ukraine. The conservation unit №2–14185.

The construction of the industrial giant, the DniproHES (the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station), which started in 1927, became an extensive propaganda campaign that was to demonstrate the greatness and the possibilities of the socialist country USSR to the world. However, there were numerous issues behind the façade of successful industrialization, from the lack of construction material to the difficulties in supplying food and accommodation to the workers.

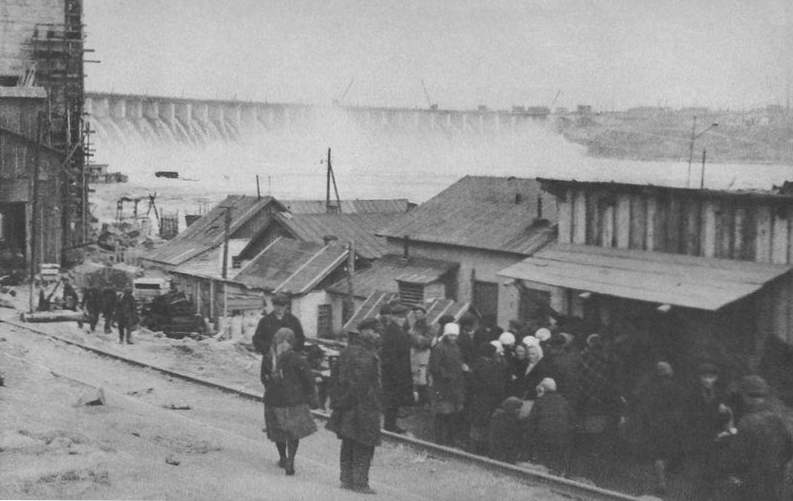

Photo from the book: Abbe James. I Photograph Russia. New York, 1934.

For example, this photograph, made in 1932 by the American photographer James Abbe, depicts workers waiting in a bread line. The unfinished DniproHES dam is in the background. Although taking pictures of any queues in the USSR was prohibited, Abbe managed to capture the real state of things. He became one of those foreigners who managed to see the real truth and to tell it to the world despite all the efforts of the USSR propaganda machine to conceal the actual situation.

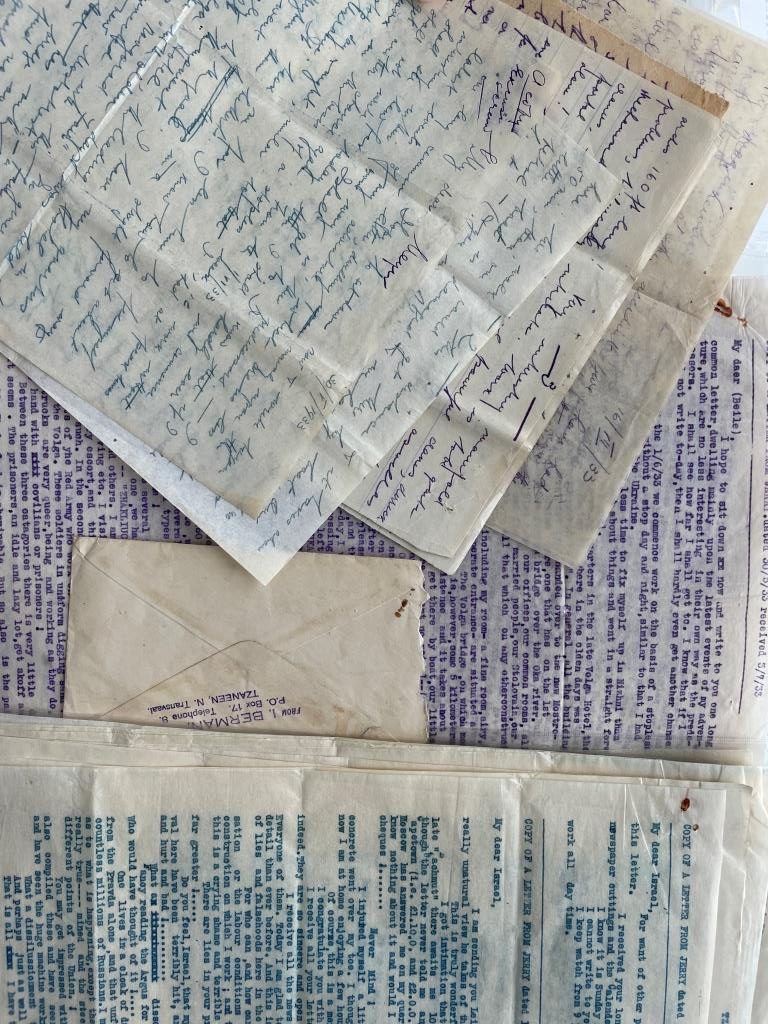

Other unique documents of the time also become a testimony of the catastrophic situation of the industry, e.g., the letters of the engineer from South Africa, Jerry Berman, who stayed in the USSR as an invited foreign specialist at the construction of the bridges.

“Every month gets worse & worse, so that month I get cards on 4 workmen, i. e., one card to be divided between 4 workmen & their families. i.e. each one gets “nothing”!! Here we all work for bread only. We get nothing else, except a few roubles. Hence a man, his wife and four children, if the first two work get 800 plus 600 gr. i.e. 1 ½ klg. Bread for six. Remember there is nothing else,” the engineer wrote to his friend in Great Britain on December 6, 1933.

The letters of Jerry Berman in the collection of the Holodomor Museum

Shortly after, the situation deteriorated:

“The scenes at the Stolovaia; of workmen, digging potatoes peel in rubbish heaps! Workmen of the bridge! How can one fine them??. What can you take away from them! Only their ‘chains’ of slave like labour!… /…/ How can a foreman work and stroke two boilers working eight hours and getting for his labour 800 gr. black bread and money to buy in a filthy-stable-stable-like (worse than Native African Eating Rooms) Stolovaia a plate of cabbage soup-meatless – and two sponfulls of ‘porridge’ (?) ‘Kasha’!!!”

These and other letters are stored in the funds of the Holodomor Museum, and they can be viewed in the Museum’s Hall of Memory.

The Holodomor: food confiscations

And yet, the situation in the kolkhozes was even worse. In particular, the mother of our hero, Maria Vyniarska, worked in the kolkhoz and earned a mere 400g of bread for one workday, trudoden. In autumn 1932, the woman brought a few buckets of grain home. It was her payment for the whole year which she should use to feed her big family (Dmytro also had a sister and three young brothers; the youngest one, Ivan, was only two years old during the Holodomor).

During the Holodomor, Dmytro Vyniarskyi was 9 years old, so he remembers all the terrors of that time.

A trudoden (a “working day”) is a form of accounting of work and payment of a kolkhoz worker, implemented in 1930. The trudoden in the kolkhoz could be completed only by a physically fit person. Giving out grain for trudodens was prohibited until the kolkhoz could meet the norm of the grain procurement plan. In spring 1933, 48% of kolkhozes in the USSR did not supply the workers with bread for trudodens.

Dmytro Vyniarskyi. Photo: Holodomor Museum

The activists, which were coming to confiscate the food, did not hesitate to take away the last crumb. They used special dipsticks called shchups which helped them to find hidden products. As the witness of the genocide recalls, the communists didn’t starve in the village, since they robbed the food and other things during the raids.

“Shchups,” sharpened metal sticks, were inherent attributes for the patrol brigades that seized the grain in 1932 and 1933. In particular, shchups were used to search for the food buried in the ground, hidden in the heaps of straw, at the attics/lofts of houses and other places.

To save at least a bit of food, Dmytro’s mother hid a little sack of millet on the stove and put her kids there hoping that they would not be touched.

“And we, like those little chickens, sat there, gathered in the corner on that little sack, and that little sack was dragged out, noticed, and taken away. There was some flour in a tub, it was also taken away… they scraped that flour…,” the man recalls.

They also took away a little stock of peas and beans. No more food was left for the family. It is evident that the crumbs of flour and millet could not influence the accomplishment of the so-called grain procurement plan. The real goal of the сommunist totalitarian regime was the extermination of Ukrainians.

Survival

The family was saved from starvation thanks to their cow. She was giving a little milk since the cows were bound to plow and harrow in the kolkhoz due to the lack of horses. As a result, the exhausted animals milked worse. Moreover, almost all the milk was taken away, and workers were given back nutrient-deprived leftovers, after the milk was processed in the separator.

To survive, people ate food surrogates. Ukrainians hunted small animals, especially gophers. These animals were caught by filling their burrows with water:

“We survived. Father and mother were swollen from starvation, swollen, and we, thank God, survived, but were not swollen. What we ate was orach, motherwort… The spring came, we started watering out gophers, brewing orach… Now the gophers are exterminated, there are no gophers, but back then there were a lot of gophers. I was just a kid, I was taking a bucket and watering them out of the holes. I would skin them, and my mother would cook a broth, and we would drink it.”

Orach, a plant that was often used as a surrogate of food during the Holodomor-genocide.

The most impressive in these words is a will for life that manifested itself right from childhood, and, unfortunately, was a common phenomenon in 1932-1933. Children are a category of the Holodomor victims that suffered the most. We can confidently say that the result of the genocide is the loss of a whole generation of boys and girls that could have become medical professionals, teachers, scientists, engineers…

The citizens of Chervonyi Yar also went stealthily to the kolkhoz’s field for spikelets left after the harvest. This was prohibited under the fear of criminal punishment:

“The punishment for stealing spikelets was severe. It could go to waste, but don’t touch it,” Dmyto Vyniarskyi says.

The document that implemented the criminal liability for collecting the ears of grain after the harvest is the resolution “On Safekeeping Property of State Enterprises, Collective Farms and Cooperatives and Strengthening Public (Socialist) Property” enacted on 7 September 1932. Among the people, it was called ‘the Five Ears of Grain Law’. A secret instruction for the application of this resolution dated 13 September 1932, provided for execution by shooting, or, “under extenuating circumstances, the punishment was at least 10 years of imprisonment with the confiscation of the property for a few grains collected at the kolkhoz field. A few fellow villagers of Dmytro Vyniarskyi fell within the scope of this instruction.

In 1932-1933, the neighbors of the Vyniarskyis were dying in whole families. After the Holodomor, the Chervonyi Yar village lost about a quarter of its population. There was no one to bury people who died from hunger. No one kept the traditional funerary customs.

“The neighbor buried the dead, there were no funerals, nothing. The neighbors buried the dead.”

Hungry death became a routine for adults and children, which undoubtedly influenced those who survived. Unfortunately, the continuous psychological effects of the Holodomor still have a negative impact on the development of our country.

During the Holodomor, there were many cases of prosecution for attempts to save other people from starvation. Our hero recalled one of these family stories. The uncle of Dmytro Vyniarskyi, Oleksandr, was the head of the kolkhoz in the neighboring village of Chumaky. To help starving fellow villagers, he supplied them with bread advances from the first harvest. However, the regime did not excuse him for these expressions of humanity. For his “samovolka,” he was imprisoned for three years.

After he returned from jail, he worked as an ordinary kolkhoz worker. These punishments for humanity during inhuman times were typical for the 1930s. Despite the prison sentences that these people received from the regime, a kind memory about the saviors still lives here and there in the Ukrainian cities and villages.

A food supply for trudodens in the ‘Vostok’ artile in Shevchenkove village, Petropavlivsk district, Dnipropetrovsk region.

A propaganda photograph. 1933. The source: National Book of Memory of Victims of the Holodomor 1932-1933 In Ukraine.

Dnipropetrovsk region. Dnipropetrovsk, ART-PRESS, 2008, p. 1236.

A common propaganda trope of Holodomor deniers is that the famine was caused by a bad harvest. Dmytro Vyniarskyi objects to this thesis:

“Everything was exported, everything went abroad. One cannot say it was a bad harvest, the yield was lower, but they were stealing, stealing, stealing everything. And people stayed with nothing… There was already no grain, everything was pumped out, taken away,” the witness of the Holodomor recalls.

Famine in 1946-1947

During the massive artificial famine of 1946-1947, Dmytro Vyniarskyi lived in Kantserivka village of Zaporizhzhia Oblast, where he still lives now. That famine was not as terrible as the one in 1932-1933. However, exhausted people were still taken to jail for collecting grain left in the fields:

“At that time, it was a little bit easier… There was still a cow, and we were secretly collecting the grain. Of course, we did it secretly, so no one could see it because you could be prosecuted. A neighbor, a fellow neighbor, also spent three years in prison for collecting ears of grain.”

The man still keeps at home the millstones that he used to grind the grain in 1946-1947 with. They were bought by his father, Denys Vyniarskyi.

Dmytro Vyniarskyi with his wife

The family of Denys Vyniarskyi survived the Holodomor, as well as the mass artificial famine in 1946-1947, without losses. However, millions of Ukrainians became victims of genocide and other Stalin’s crimes. The communist totalitarian regime neglected basic human rights, including the right to life, dignity, freedom of opinion, etc. The task of the current generation is to save the memory about these crimes to avoid their repetition in the future.