The memories of the Holodomor, recorded by the witness Kateryna Zavrotska in the early 1990s, were handed over to the museum

Maksym Bazhal from Kyiv handed over the memories of his aunt Kateryna Havrylivna Zavrotskaya (née Bazhal), 1919-1995, to the Holodomor Museum. As a 13-year-old girl, she survived the Holodomor in the Romny district of the Sumy region. Before that, the family of her father Havryl Bazhal, in which four children grew up, was disbanded, and the head of the family was arrested and thrown into prison. They all survived thanks to good people who shared the last even in that difficult time. Kateryna Havrylivna graduated from the Dnipropetrovsk Medical Institute and worked as a gynaecological surgeon in a hospital in Lysychansk all her life, where she was known and respected by everyone. After all, she saved many lives of pregnant women with pathologies.

In 1949, she married Józef Zawrocki, two daughters were born in the family – Tetiana and Victoria. But family happiness was short-lived. In 1963, Józef died from a head injury he received in the winter when he was on call to sick children (he was a paediatrician). Kateryna Havrylivna raised her daughters alone and worked hard. In the last years of her life, she began to record her memories, which she finished on March 3, 1992. These records, made in an ordinary thick notebook, are kept by Tatyana’s daughter in Kharkiv. She kindly gave it to her cousin Maksym Bazhal for temporary use, and he digitised these memories and shared them with us. We sincerely thank you because every such testimony is crucial, especially from people we will never be able to ask again.

Kateryna Zavrotska’s memoirs are also valuable in that she described in detail the life of the family and village community before collectivization and dekulakization, when life was prosperous and happy, filled with hard peasant work though. But among that work, there was a place for rest, study, self-activity, and even theatre!

However, all this was destroyed in the early 1930s, and then finally buried by the Holodomor.

So, the word belongs to the author of the memoirs, Kateryna Zavrotskyi (translated from Russian to Ukrainian).

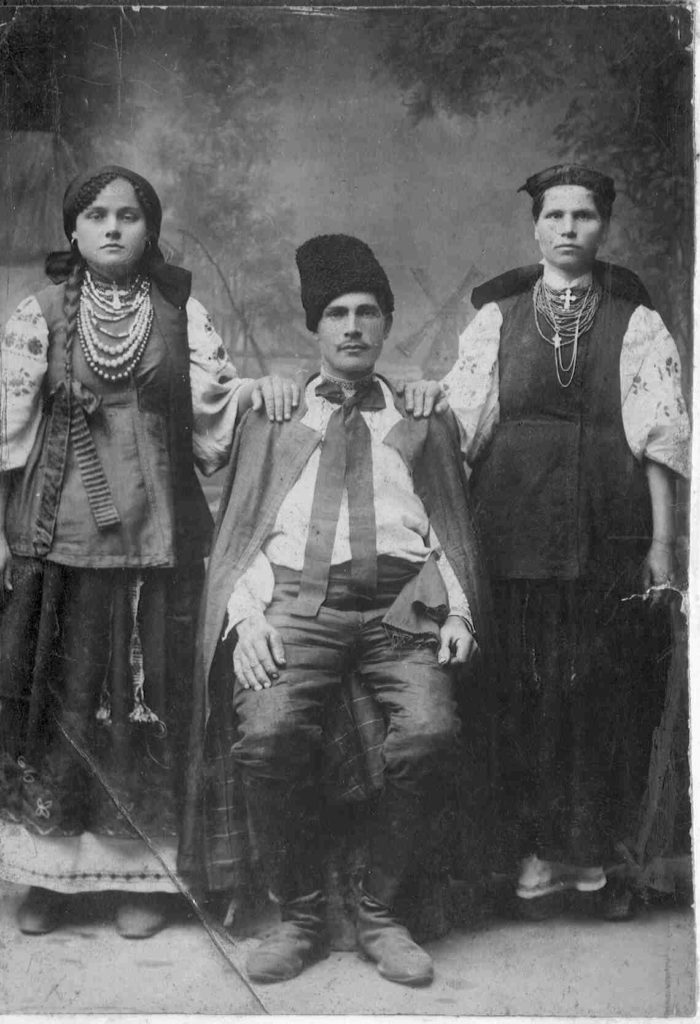

Kateryna Havrylivna Zavrotska (Bazhal), 1919—1995, with her husband. She was born in Levondivka, Romnt district, Sumy region. The eldest daughter in the family, after finishing school in Romny, entered the Dnipropetrovsk Medical Institute. In 1949, she married an ethnic Pole, Józef Zawrocki (1914-1963), and they had two daughters, Tetiana (1950) and Victoria (1955). (Here and further notes under the photo – M. Bazhal).

CHILDHOOD

The period of my life up to the age of thirteen can be called the happiest, happiest childhood. It coincided with the development of the country’s NEP, that is, the New Economic Policy, which was characterised by a flourishing economy and life when private ownership of land and the means of production was allowed. All people during this period lived in prosperity because they worked for themselves, on their land with full dedication. People in our village loved the land. Perhaps, like everywhere in any village. I recently watched a documentary about Amosov, where he said that private property is an inseparable organic part of the human personality. There is no better way to say it, it really is so.

It was necessary to see with what love people cultivated their land: they got up early and went to bed late; each tried to make their harvest better and bigger than the other’s so that their livestock and yard looked better than their neighbour’s. This was a competition, but only free, without force, without instruction; it came out by itself, it happened naturally, and in this way, the competition was carried out. I remember each owner fattening his stallion during the winter, and in the spring it was being taken out to the pasture for running. All the people came out to see it, it was a unique sight! The horses were, as it were, better than each other – the washed, cleaned skin on them played with all the colours of the rainbow, and the owners, looking at them, were happy and proud of their treasure.

But it cannot be said that these people were locked in private property interests, they were also characterised by collectivism, public opinion, and public interests, they lived together in joy and trouble, helped each other, and performed laborious work together, in a group.

So, in the summer, when the harvest began, people gathered as the whole village and threshed grain for each owner, in turn, carried the threshing machine from yard to yard and threshed it all together. Women prepared dinner for all. Everyone worked and ate together, with drinks, of course, and songs. They ended the working day cheerfully, and in the morning they went to the next owner. In the spring, when the grass bloomed in the meadows and the flowers bloomed, every Sunday all the people, old and young, gathered in the meadow, had a party, sang, played, danced, collected flowers, and had a good time. In winter, women gathered in one house, spun yarn, sang songs, talked about this, about that, and shared the news. During autumn, women would come together to help each other cut cabbage and have conversations. This normal human interaction left me with pleasant memories and had a positive impact on me. It helped to shape a healthy moral foundation within me. I’m not sure if Mykola and Maria remembered this time, but for me, it was a piece of a happy and carefree childhood. (Mykola and Maria are Kateryna’s younger brother and sister, as noted by Maksym Bazhal. – Ed.).

I remember very well the village where we lived. Obviously, these were still Stolypin farms (such farms appeared as a result of the Stolypin reform, aimed at increasing the efficiency of agriculture. The main idea of the reform was the transition to farming. – note by M. Bazhal).

It was a small village with about 100 yards. It was called Levondivka – named after Mr. Levandovskyi. It was beautiful, everything was drowning in gardens. At the end of the village, there was a pond, and beyond that, a meadow with haystacks. All the yards were enclosed by fences, forming an oval shape. In the centre of the village, there was a lovely brick building – our four-year school, surrounded by pyramidal poplars and acacia bushes trimmed to the level of the fence. Flowerbeds adorned the schoolyard, and the schoolchildren themselves planted and tended to these beds, with each class having its own designated area.

Havrylo Svyrydovych Bazhal (born approximately 1891-1895, died approximately 1968-1970) was originally from the village of Levondivka, Romny district. His father was a wealthy farmer, he owned land. After the death of his father, Havrylo inherited part of the land and became, according to the ideas of the Soviet authorities, a “kulak”. During forced collectivization, his property was taken away, and he was arrested.

People planned the yards in a way so that the house overlooked a pasture, and the vegetable garden and garden extended deep into the yard. Everyone’s yards were well-kept, swept, cleaned, surrounded by fences, paths sprinkled with sand. Each owner tried to make his yard no worse than his neighbour’s, that is, they competed.

I’ve already mentioned that at the end of the village, there was a pond with reeds. The pond was inhabited by crucians and carps. I All the people used to fish – some with a fishing net, some with a bucket. We also used to go fishing and swim in this pond in the summer. And in winter, we used to go ice skating and sledging. We made saucer sledges from straw and horse manure. We formed a basin shape and poured water into it every day, which froze and created an icy bottom. Then we would sit in the sledge, and it would speed down the mountain, making a whistling sound as the wind rushed past our ears. It was incredibly thrilling!

The centre of culture in this farmstead was the school, or rather the teacher who worked there – Anton Danylovych Kaliuzhnyi. A descendant of White Guard officers, he was an extremely well-educated and cultured person and a true Teacher in the full sense of the word. He sowed the eternal, good, and just. His wife – a true aristocrat – helped him in everything. They lived near the school. Apparently, fate accidentally drove them into such wilderness (such people then saved themselves as best they could). I studied for four years, that is, I graduated from elementary school with this teacher and took the first steps in education. This training left me with the most pleasant memories for the rest of my life. Only now do I understand what the first teacher is and how important he is in the life of every person!

It was the same Sukhomlynskyi. Anton Danylovych laid the foundations of my future life in me; he became a guiding light for me. Wherever I later studied, I always excelled, and it seems to me that it is only thanks to him that he laid the groundwork in science. When I became an adult and had my own children, I personally chose their first teacher, being mindful of all kinds of truths and crooks.

There were few students in our first school in Levondivka. Therefore, the teacher could devote a lot of time to everyone, and he worked with everyone individually, diligently, with absolute dedication, and gave everyone a part of his soul and heart. At the same time, he was strict and demanding: if someone did not complete their homework, he sent them home. But there were few of such because it was simply shameful to come to him with unlearned lessons. Kaliuzhnyi knew how to conduct classes interestingly, and during the break, he organised interesting games with us. We were under his supervision all the time, and he did not let us out of his sight. During the summer holidays, he organised hikes and took us on excursions to the city, landowners’ estates, forests…

Anton Danylovych chose the most beautiful corners of nature and involved us in it, explaining how each insect, bush, and grass grows and develops. In the forest, we cooked porridge, or rather cooked. We collected firewood and ate together by the fire. The teacher told us interesting stories and fairy tales. Then, we collected flowers and plants for the herbarium and played different games under his guidance. At school, Kaliuzhnyi organised a lively corner: there was a squirrel, a hamster, and a hedgehog. We fed them and brought food from home. Why do I dwell on this in such detail? Because I remembered it for the rest of my life.

I remember that the school had a huge hall, and at the end of it – a huge stage with a curtain and scenery, which, by the way, Anton Danylovych painted himself. On this stage, we often performed in front of our fellow villagers as artists: we sang, danced, recited, acted out small plays, staged fairy tales… So, for example, in the fairy tale “Little Red Riding Hood” I was a granddaughter, and in “Grandfather and Turnip” – a mouse. This is how other children participated in various roles, and Anton Danylovych himself and his wife were engaged in this: she sewed costumes for us, took part in rehearsals, and made her adjustments.

Such people brought culture to the masses and engaged in the real education of the growing generation – not in words but in deeds. This teacher probably instilled in me a love of science since childhood. True, I probably had a desire to study from birth, because at the age of six, I really wanted to study at school and I asked my grandmother to enroll me in school. She took me to the teacher for this purpose, and he said: “Let her run a little more!” I immediately answered: “You wait here, and I will run a little and come to you now!”. He laughed, of course, but allowed me to attend school as a free listener. I went to school with great pleasure with my cousin Hrysha, who studied very poorly. He was often punished by the teacher, and embarrassed in front of all the students. And I was ashamed of him and sorry for him, that’s why I cried.

Remembering this teacher now and analysing it, as an adult, I think that he was probably a gifted person by nature, he played the violin well, knew how to pick voices with the help of a tuning fork, organised a singing group and a drama group of adults in our farmstead. They staged such plays from Ukrainian classics as “Natalka Poltavka”, “Beztalanna”, “Stolen Happiness” and others. My parents played the main roles in these plays. My mother played Natalka, she had a pleasant voice, and my father played Mr Voznyi. It must be said that my father was an advanced and cultured person in our village, gravitated to culture, to knowledge of the world. He maintained friendly relations with this teacher, helped him in all these activities, helped to make a scene at school, and went to the city for costumes (they were rented from the theatre); so they acted like real artists. Anton Danylovych was their director and producer.

On the left – Marfa Kostiantynivna Bazhal (Khilko), 1899—1971. She was born on a farm near Levondivka. Her parents cut a clearing right in the forest, built a house and settled down to live there, they ran a subsistence economy. They were poor, but they had enough for life. Photo of the pre-revolutionary period.

Both father and mother were literate people for that time, they received a four-grade church-parish education, and the mother even had a certificate of commendation. We even had our small library: Tolstoi, Hohol, and Chekhov were there. My father loved Ostap Vyshnia very much, he used to tell his humorous stories by heart. There was also “Robinson Crusoe”, I read it in early childhood.

One day I overheard a teacher persuading my father to continue my education because he thought I had what it took. Father promised it was not difficult for him because we were financially secure. As I have already written, my father had 7 hectares of land, which brought a suitable profit. In addition, he was engaged in small trade – it was his hobby, he loved and knew how to trade. So, in the village, my father bought live pigs from people, butchered them, processed the carcasses and took them to the city to sell, and we ate fresh meat every day. Grandma cooked very tasty sausages; she stuffed intestines with flour, potatoes, and porridge. We ate well and dressed well.

COLLECTIVIZATION AND HOLODOMOR

This period of our life began in 1931, or maybe even earlier, when collectivization began in the countryside. It all started with the fact that representatives from the city came to the village, gathered people to the school for a meeting and vigorously campaigned to join the collective farm. But no one voluntarily agreed. It lasted for about a year. Then, the same representatives from the city began to arrive in whole brigades on trucks, went to every yard, and looked for grain, flour, and food. They did not stop by anything: they took everything they found, put it on pallets and brought it to the city. I remember them using metal ramrods to pierce the piles of straw, the dirt floor and just the ground in the yard – they felt where everyone had something hidden and took it away by force, despite the cries of children and mothers. No regret, no compassion for either children or the elderly! It was a terrible sight. It was a real robbery! And so it went on for about a year.

Finally, 1933 came – a real general hunger strike. All stocks, who had even something left, were eaten. People began to eat grass and tree leaves, and they began to get sick and die of hunger. Those who could still move went in different directions.

Even before the hunger strike, people in our village were divided into three classes: kulaks, middle peasants, and poor people. Kulaks and poor people were few and far between. The rest are middle peasants. Uncle Hrytsko and I got into kulaks because we each had 7 hectares of land, and the rest – 5-6 hectares or less. Also, two Radchenko brothers were included in the kulaks because they had a threshing machine, which they used to thresh people’s grain. And so we, the four owners, began to be evicted. The Radchenkos, both brothers, immediately went to the city, leaving everything behind, and we stayed and waited for the abuse that would be done to us. At first, they came and arrested the father for nothing and put him in prison. We were left alone with our mother and four children. The youngest was Vania, he was four years old, and he had tuberculosis of the knee joint. Grandma was taken by her youngest daughter, Iryna.

Although people did not want to go to the collective farm, they started to build it anyway. For this, all the land was taken away; even the one under the gardens and estate. They took the barn, threshing floor, barn, horse, cow and poultry. All that was left was a big lame mare, on which my mother rode to visit relatives and earned food for us because we were left without means of subsistence. In our only house, a public hairdresser was arranged. Men came there to get haircuts and shaves. They were smoking, spitting and talking, and we were sitting on the stove and had to listen to all that, waiting for our mother to bring us something to eat. Then, she stopped getting it because the people did not have anything either – everyone was starving and survived as best they could. Many died, some went to Donbas and escaped from hunger there. We continued to sit and starve and began to eat tree bark and frozen potatoes.

I remembered the episode of us getting those potatoes. Not far from our village, there was a state farm where mismanagement prevailed, like everywhere in state farms. And there, the potatoes lay frozen in piles. Of course, it was thrown into the garbage, and people rushed for it and began to collect it for food. Mykola and I also ran there to collect potatoes, but it wasn’t there! A stout man began to hit our hands, not to let us take some potatoes. We were crying and screaming, and another man defended us and asked, “Why are you hitting children?” The man responded, “Don’t you see whose children they are? These are Havrylo’s children!” So, according to his mindset, it seemed that if we were Havrylo’s, we had no right to eat even frozen potatoes! This experience planted anger, hatred, and resentment in the children’s hearts for their entire lives.

So we continued our poor existence somehow. And in the early spring of 1933, when grass and leaves appeared in the trees, we began to eat them. People who went to the collective farm were given some sort of soup. But we didn’t have even that because, as kulaks, we weren’t accepted into the collective farm. It is unknown what would have happened to us if our father had not escaped from prison and taken us to the city.

Here, it is necessary to describe how exactly he took us away. I have already said that we lived on a stove, and then, from there, they kicked us out, too. Like, we interfered with the work of the hairdresser! A neighbour sheltered us. Apparently, she was a kind woman. Her name was Palazhechka. She hid and kept us in secret so that no one would know. During the day, she hid us under the table – and covered us with a long tablecloth. At night, we slept in a regular way. This kind woman fed us as much as she could, shared the last, and she also had four children of our age! And so, I remember my father coming at night (he was searching for us with difficulty) and saying: “Get together, let’s go to the city!”. We had nothing to collect. The neighbour fed us, and we left like that. We were walking quietly, sneaking under the fences, like some kind of criminals so that no one would see us and stop us. We left unnoticed. It was the spring of 1933. The night was dark and cold. It was raining, and the road was washed away. We could barely get our feet out of the mud, and we were wearing torn boots. Our feet were soaked, our clothes were wet, and we were freezing, but we kept walking and walking. Father and mother took turns carrying Vania in their arms (and it was a distance of about 15 km!).

Ivan Havrylovych Bazhal (1929-1982), Maksym Bazhal’s father, at the age of 9. “Swollen from hunger during the Holodomor. He slipped on the wet floor while sister Katia was washing it and he broke his right leg at the knee.

His body was weakened, and his knee was rotting for six months. The hospital in the city of Romny was overcrowded, and they did not admit Vania. Kateryna’s school teacher knew about the difficult situation in the family, so he took the sick Ivan, brought him to the hospital and left him in the reception department. They had to keep the child with them. There were many such children then. It was not just a hospital, but a boarding house where children were fed and treated and educated. There were various clubs where children mastered the basics of various professions: musicians, artists, locksmiths, carpenters, etc. My father’s knee healed, but his leg did not bend for the rest of his life. He stayed in the boarding house for four years! There, he learned to play all stringed instruments – mandolin, guitar, balalaika. Later, it fed him at school (they travelled with school amateur concerts) and at the institute (he led the orchestra of folk instruments). He graduated from the Kyiv Technological Institute of the Food Industry and became a sugar engineer, doctor of technical sciences, professor, and head. Department of sugar and sugary substances at the Institute of Colloidal Chemistry of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine”.

With difficulty, we reached the city and settled in the basement of a small house where my father’s acquaintance, a Jew, lived. Apparently, he was also a good person. Our father made a preliminary agreement with him when he escaped from prison. This Jew also had four children of our age: Ziama, Chaim, Liza and Borys. Soon, we became friends with them and shared our sorrows because they were also poor. Together with them, we collected potato skins from the garbage and simply fried them on the fire. So we ate the same thing.

In the city at that time, as well as in the village, there was a terrible famine and typhus raged. Everyone, except me, fell ill with typhus and was sent to the hospital. It saved us from starvation at first. So, we lived in this basement room, which consisted of one small room. There was one bed where we, the children, slept on it, lying across, and the father and mother – on some platforms. And so, we lived in a basement in the city without means of subsistence, without money, without an apartment, without a residence permit, without the right to exist and to live in general.

It is noteworthy that bread was sold in shops in Kharkiv, although there were colossal queues behind it. And in Romny there was no bread at all. People died on the move, lying dead on the streets, and in devastated houses, they did not have time to remove the corpses during the night. And there was no one to take them out because the people were weakened, they could barely walk, I saw them – both alive and dead. God forbid I will never see such a thing again, it is a terrible sight. Already at the medical institute, I learned that there are two stages of starvation disease: dry and swollen. And indeed, I saw those people. Some were swollen, with cracked skin, from which water flowed, and next to it – a light skeleton covered with skin. But everyone’s eyes were the same: dry, with a terrible look. And there were many such people, they were lying on the hill that descended from the bazaar to the suburbs where we lived. Better not to mention!

There were even rumours that in one house next to ours lived people who caught small children, cut them up made jellied meat out of them, and then sold it in the bazaar. People knew about it, but they bought it and ate it.

I missed another moment: once my father sent me to a distant village and made me a nanny (to nurse a small child in the family), although I was still a child myself. But he thought that in this way he would save me from starvation. He told me that if I drank one glass of milk a day, I would stay alive. So, I measured how many spoons could fit in a glass and counted the spoons when I ate from a common bowl. I must say that my hosts’ milk was worth its weight in gold. They were also starving, eating weeds and tree leaves. The leaves were dried and ground, the weed was boiled, and matorzhanyky were baked from this mixture. We ate them and drank milk. I couldn’t last long on such food and ran away from there. I walked 50 km alone.

Since 1934, starvation subsided, and bread appeared. First, it was on ration cards and then on free sale. So, life gradually started to improve, and starvation no longer threatened us. Even our youngest sister, Vira, was born.

Bazhal’s brothers and sisters with their mother Marfa at Ivan’s wedding. From left to right: Kateryna Havrylivna, Mykola Havrylovych, Marfa Kostiantynivna, Maria Havrylivna, Ivan Havrylovych Bazhal, Halyna Petrivna (my mother), Petro Porfyrovych and Kateryna Illivna Voronezhsky (grandparents on my mother’s side). Missing from the photo is Vira Gavrylivna Bazhal, 1934—1941?, the youngest daughter in the family. She disappeared in 1941 after being evacuated with the orphanage. She was never found, although her brother Ivan Havrylovych submitted requests to the Inyurkollegiya of the USSR every few years throughout his life.

Mykola Havrylovych Bazhal, 1921-1984, was a veteran of the Second World War, captain, commander of an artillery battery, and participant in the Battle of Kursk, awarded with many orders and medals, including the Order of the Combat Red Banner. In the autumn of 1944, near Lake Balaton in Hungary, he received a third (severe) wound, due to which he lost his right arm. After the war, he graduated from the Odesa Institute of National Economy, worked there, became a professor of economics, headed the banking department, and was vice-rector.

Maria Havrylivna Topliashvili (Bazhal), 1924—2013. She came to Germany as an ostarbeiter. In 1945, she met Symon Topliashvili there, who became her husband. She lived in Tbilisi for many years and worked as a seamstress.