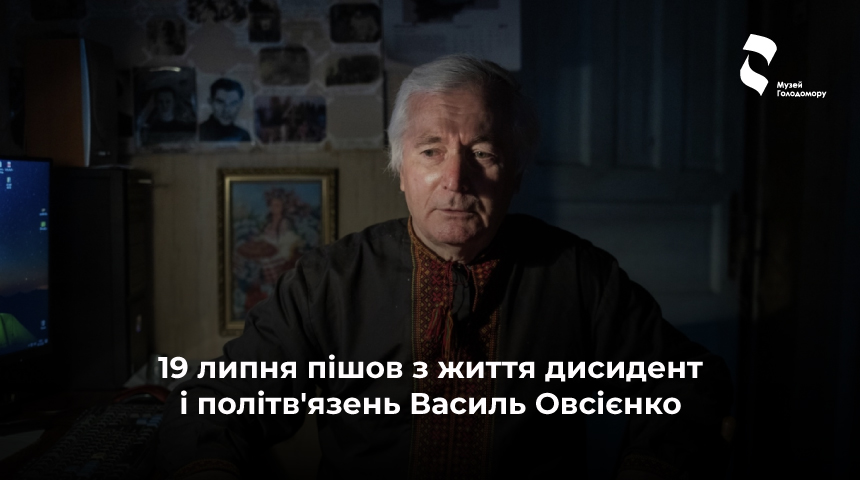

Dissident and Soviet political prisoner Vasyl Ovsienko passed away

Vasyl Ovsienko, a well-known public figure, dissident, political prisoner of Soviet camps, chronicler of the resistance movement, Ukrainian philologist and journalist, passed away on July 19 at the age of 75.

He was born on April 8, 1949, in the village of Stavky, Radomyshl district in Zhytomyr Oblast.

“Our family was big. Our parents had ten children. I was the ninth, the youngest, because my sister was stillborn after me, – Vasyl Ovsienko recalled . – Father, as they say, from the “farmers”, had two grades of education. Although the mother was illiterate, their family was distinguished in the village by a kind of innate intelligence. My parents got married in 1930 and enrolled in a collective farm. They lived with my father’s parents for a year, so they bought an old hut in Khomivka, and after a few years they built their own. For that time, it was big. No wonder the Germans occupied it during the war, and the family huddled in a dugout for some time.

…In the new year of 1944 (the Germans even put up a Christmas tree in our house), the Reds struck and finally occupied our region. I don’t say liberated because collective farm serfdom returned and again the famine of 1946-1947. At least there was no famine under the Germans.

And before that, the famine of 1933 claimed 346 lives in Stavky (a third of the village). Vasyl Stepanovych Batsuk, known as Halivei (he probably meant Galileo because he was a very wise and cunning man, Heaven bless him), said this figure to me in 1977. Some now doubt this figure. Of course: they didn’t keep records of those who died of starvation, but they trampled the cemetery like barbarians, paved the road along it, pilfered crosses for firewood, pilfered tombstones … In a word, they fell into barbarism.

Mother told me how, during collectivization, 50 families were taken out of the village. Not all of them were “kulaks”. A paper came: send 50 families. Whom? The village authorities determined: this one spat in my borscht, that one – ploughed the land limit, and this one is not needed in the village. In 1937, 19 people were arrested in one night – an accountant, an agronomist, and more and more literate people. Even as a child, I sometimes secretly listened to how the elders talked about collectivization, how “kulaks” were evicted from the village, about the famine of 1933, and the war. Shells of river molluscs were lying under the huts: it was them that people saved themselves from hunger with. They also taught us that it is possible to eat quinoa, sorrel, buttercup, jersey cow mushrooms, hare sorrel and hare garlic, acacia…

The church in Stavky was famous throughout the district. In 1935, it was dismantled, and the tree was cut down (on some collective farm buildings and houses, I remember, for a long time, the faces of saints were visible from under the whitewash). And from the rest of the wood, they built a club.

We didn’t talk about politics in the house, but someone taught me to reply the question: “Who is your father?” climbing onto the bench and pointing to the portrait of Stalin. It was on the green cardboard of the wall calendar. I did not feel ideological differences with myself when I sat on the mud and sang: “The hammer and sickle – death and hunger.” Then my mother beat my lips. My mother did it with a towel, so it didn’t hurt much.

And my father sometimes got drunk and brutally beat my older brothers. And sometimes my mother. I still can’t understand and forget those terrible pictures… Maybe it was out of desperation: my father was a very hard-working man. If not for “real socialism”, then he would have been a strong master.

During the day, my father worked as a groom on a collective farm, at night, he grazed the horses and never got enough sleep. He was covered with boils from a cold. He was attacked by a wolf in a meadow. When the brothers grew up, he sent them at night, while he travelled somewhere, and traded something (this was called the terrible word “speculation”). He brought something from the field in a bag or bundle but never sent us to steal from the collective farm.

They told how the father saved the family in 1946-1947. He resold some things, bought and slaughtered calves and took them to Kyiv, went to Halychyna to earn money.

We did not dare to say a bad word to someone or take someone else’s; we did not wander in other people’s gardens. We had several apple trees for which tax in kind was extorted. I still remember how a strange man, who was called the terrible word “finagent” (with a stress on the “a”), walking around the garden with my father, counting the trees and currant bushes. He looked into the barn to see if there was no more than one cow and one pig. It was obvious that the father, who was so strict with us, was afraid of this “finagent”, and that fear was transmitted to us. Power was not talked about in the house, but the fear of it was always there. The authorities were strange and hostile: “they” and “we”.

As soon as the iron shackles of Stalinism fell, my father planted a garden in the first year (1954) and started beekeeping. My father’s cousins sent them from Synelnykovo via mail – it was a great miracle for the whole village: bees were sent by mail! And my father also planted currants, cherries, garden strawberries.”

“When I was tried for the last time in 1981 in Zhytomyr, it was also recorded in the verdict that I spread slanderous fictions that there was some kind of famine in Ukraine. My mother was sitting in the hall, she certainly knew what it was, and there was also Demchenko, a teacher from my village, who claimed that nothing like that had happened. I did not argue with him, because then it was a completely useless matter. Even Judge Biletsky was uncomfortable listening to this, so in order for me to be a slanderer, he recorded that I told someone about the famine in 1938, not in 1933, and that then “the entire Ukrainian people died.” But not all, but only a third. Because then how would I appear?”

Then Vasily Ovseenko was sentenced to 10 years in camps of especially strict regime and 5 years of exile. Seven years later, in 1988, without a petition, he was pardoned by a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. In total, he served his sentence three times and spent 14 years in prison.

“He was a great and very modest person, an ascetic, whose units millions,” journalist and editor Vakhtang Kipiani wrote about Vasyl Ovsienko.

The bright memory of the deceased!