Kharkiv during the Holodomor-Genocide

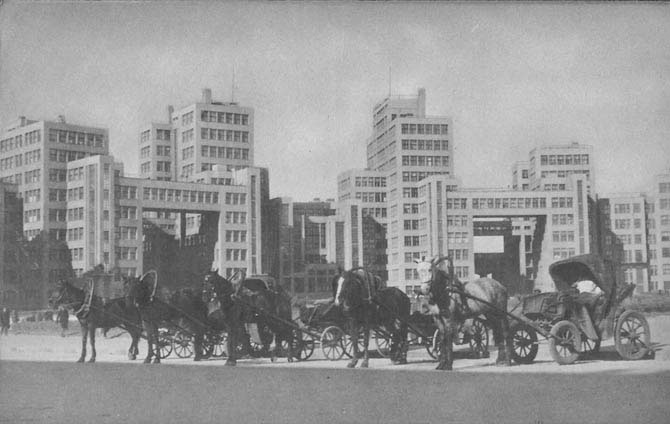

Kharkiv became the capital of the Ukrainian SSR in 1919. The Kharkiv oblast (covering the borders of modern-day Kharkiv, Sumy, and parts of Poltava and Chernihiv regions) was formed in February 1932. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Kharkiv was impressive for its large-scale development and certain grandeur.

However, the Holodomor changed the face of the city forever. The Welsh journalist Gareth Jones, who visited the USSR several times and was one of the first to reveal the truth about the Holodomor in Ukraine to the world community, wrote:

“In 1930, I saw Kharkiv, the capital of Ukraine, from the air, the masts of scaffolding towering in the city centre, where a row of skyscrapers was soon to rise… In 1931, I saw Kharkiv again. The new streets and houses struck me. The spirit of adventure reigned among the young workers… In 1933, I saw Kharkiv once again. It was no longer the city of 1930 when skyscrapers were perceived as symbols of a happy future. The spirit of adventurism of 1931 had disappeared… The buildings looked half-ruined as if no one cared about them. Many of the new buildings were empty… Village children sat on the stairs and shouted: “Uncle, give us a kopek (or bread)”. There were 4,000 to 7,000 people queuing for bread, waiting all night in the cold.

At the market, Gareth Jones saw ragged, starving and sick people wandering between the aisles. The journalist was struck by the extraordinary number of street children wandering the streets, who were being gathered by police and taken to the station. There, Jones saw what shocked him the most during this last trip: several hundred street children. One of them was lying on the floor, his face purple with fever and breathing heavily, while another boy was lying in rags on the ground, part of his body exposed, showing his withered body and thin arms.

When the famine started in Kharkiv, all corpses found on the streets required forensic examination. There were so many deceased that forensic experts had to work around the clock. After the examinations, the bodies were transported to the outskirts of the city, where they were buried in mass graves.

It should be noted that the examinations were carried out only in Kharkiv. They were not carried out in small towns and villages. Lev Kopelev, who worked in the editorial office of a Kharkiv newspaper in 1932-1933, recalled how every night trucks covered with tarpaulin collected corpses at railway stations, under bridges and in back alleys. They ran around the city during the hours when people did not leave their homes. Other similar vehicles collected homeless people. All hospitals in Kharkiv were overcrowded. The morgues were full too. All those who were stronger were taken out of town and left there. Mykola Chyrva, a witness to the events, recounted how he unloaded wagons with corpses in Kharkiv during the Holodomor. He recalled that the city authorities of Kharkiv, under the guise of the need to fight for the sanitary condition of the capital, forced homeless elderly people and children to be gathered and sent to the “depot”.

The freight cars, known as “calf cars,” were situated at the dead end of the station. People were herded into these cars, filling one carriage at a time, which were then locked from the outside. After four or five days, the carriage would be opened, and almost everyone inside would be dead. The bodies were subsequently thrown into the Saltivska chasm. Those who miraculously survived were transferred to another carriage, which was in the process of being filled. Mykola Chyrva, who recounted his experiences unloading these wagons, remarked, “It was fortunate that most of the inhabitants of the ‘depot’ were children. It made it easier to unload and load them.”

According to Holodomor witness Ivan Oransky, Kharkiv differed greatly in terms of who received food and who did not. Some people belonged to the party, employees and the like. There were many factories and industrial plants in Kharkiv, and the workers who did the hardest physical work received more food, while others had smaller rations. Ivan Oransky was a student and received 400 grams of bread a day. The same thesis was confirmed by Gareth Jones. He noticed that near the Kharkiv railway station square, where the caught starving street children were taken, a girl with a piece of cake in her hand, the daughter of a communist functionary, was standing by a carriage. Impressed Jones, wrote down: “In 1930, I noticed class inequality… In 1933, it is the most striking feature of the Soviet Union.”

Kharkiv, like any other large city in the Ukrainian SSR, was full of bread lines. The father of witness Anastasiia K. sometimes came from a starving village to the city to buy bread. Ms Anastasiia recalled how she was sometimes taken with him: “But when it was my turn to take bread, I was usually told that there was no bread left or that I was too young to buy bread. You can imagine how miserable I felt after standing in line for hours and coming back empty-handed.” The endless bread lines were confirmed by the Ambassador of the Kingdom of Italy to the USSR in his letter to the Royal Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Rome.

The Royal Consul of the Kingdom of Italy in Kharkiv, Sergio Gradenigo, in one of his reports paid special attention to the scale of crime: “It is now dangerous to walk in Kharkiv at night in districts far from the centre. It has become commonplace for people to be robbed of all their clothes. Even the old doctor of the German consulate, Dr Rose, had to walk naked. Most of the time, the bandits are not satisfied with stripping the victim of his or her clothes, but also kill them. In the morning, the naked corpses of people killed during the night are often found in the marketplace; the same bodies lie for days along the frozen bank of the Kharkiv River. These bandits treat children even more cruelly. More than 300 children have disappeared in Kharkiv over the past 6 weeks. This figure has been confirmed by numerous sources, and there is no doubt about its veracity.”

Thus, the Holodomor genocide changed the face of Kharkiv forever. It was no longer a city of dreams with skyscrapers, wide avenues, and comfortable urban space. During the Holodomor, Kharkiv became a city of contradictions: hungry, exhausted people, homeless and sick children, corpses of the dead on the streets – this was the horrific everyday life of Kharkiv. At the same time, a small handful of communist functionaries enjoyed privileges and access to all the benefits. They were the organisers and perpetrators of the Holodomor in the Ukrainian SSR, and their criminal orders starved millions of Ukrainians to death. However, they kept silent and denied the crime of genocide for decades.

Inna Shuhaliova,

Senior researcher at the Department of Holodomor Research

and Man-Made Mass Famines at the

National Museum of the Holodomor Genocide

The photo shows the Derprom building in Kharkiv in the early 1930s.

Photo by James Abbe.

Source: AbbeArchive.

Published in the newspaper ‘Ridnyi Krai’, 18 March 2025.