Zaporizhzhia during the Holodomor-Genocide

Until recently, there had been a stereotype among part of Ukrainian society that the industrial centres of Soviet Ukraine were in a relatively good food situation during the first five-year plans: allegedly, workers and employees involved in the construction of the “giants of industrialisation” had a proper food supply and were less likely to suffer from hunger. However, this is only a stereotype. Eyewitness accounts prove that residents of all cities of the Ukrainian SSR, without exception, suffered from hunger and malnutrition.

In the early 1930s, Zaporizhzhia was part of the Dnipropetrovsk region. The inclusion of this region in Stalin’s “super-industrialisation” plan served its industrial character. The announcement of the industrialisation policy led to the massive arrival of people from all over the USSR to work in construction. Civil registry records indicate that the new buildings were crowded with workers relocated from other regions. We analysed birth registries, which required the length of time the parents had lived in the area. The new buildings were mainly occupied by newcomers. Many peasants also arrived in Zaporizhzhia in search of work. However, the labour exchange did not register them due to their lack of documentation. As a result, numerous fake certificates emerged, allowing not only peasants but also thieves and the homeless to be hired for labour crews. According to the memoirs of Ivan Vasylenko, a member of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine, his fellow villagers from the Poltava region tried to reach Zaporizhzhia for a job in construction. However, almost all of them died at the Shliuzova station in Zaporizhzhia (now the Covered Market is located there).

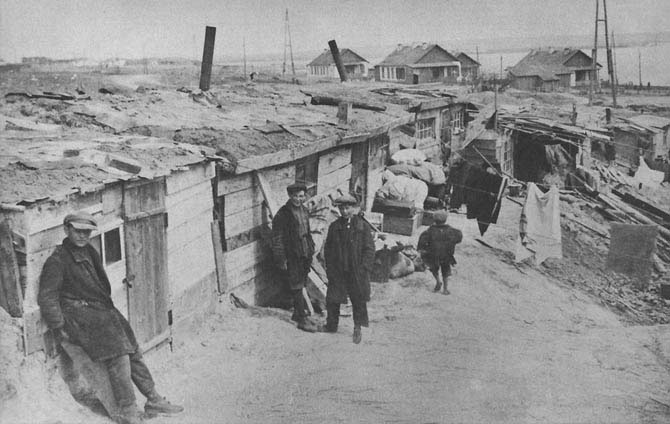

Overall, between 1927 and 1932, Zaporizhzhia was divided into two parts: the old city districts with developed infrastructure and the so-called New Zaporizhzhia, where DniproBud and factories were being built, and evictions for proletarians were only planned, so workers lived in barracks around the new buildings in inhumane conditions. They lived in dugouts and semi-dugouts located near the construction sites.

DniproHES workers’ dwellings, 1930s. Photo by James Abbe.

Meanwhile, foreign engineers were accommodated on the right bank in comfortable stone and brick cottages. They were isolated from ordinary workers. The latter were not even allowed to communicate with foreigners.

At the factories, workers received meagre food rations or insignificant wages that could not feed their families. It was typical of industrial centres during the time. According to foreign engineer Jerry Berman, who worked in eastern Ukraine in Luhansk and supervised the construction of the bridge, the level of wages for workers involved in the construction of strategic facilities was very low.

Liudmyla Yehorchenko, a witness to the events whose parents worked at DniproBud in 1932, recalled that funeral processions often took place on their street in 1932, which she watched from the window of her parents’ apartment on the third floor. As a seven-year-old girl, the grey and yellow faces of the dead and the miserable funeral processions are forever etched in her memory.

In the autumn of 1932, the chairman of the All-Union Central Executive Committee Mykola Kalinin, People’s Commissar of Industry Serhii Ordzhonikidze, the first secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine Stanislav Kosior, the French writer Henri Barbusse, the American engineer Hugh Cooper, along with well-known party and trade union officials arrived in Zaporizhzhia to attend the celebrations on the occasion of the launch of DniproHES. At the meeting, all the speakers made pompous speeches, but none of them mentioned the human cost of this ‘construction of the century’. The newspapers, reporting on the words of these speakers, praised the party apparatus for its ‘high achievements’ and did not mention the real state of affairs on the construction site and near it.

On the occasion of public holidays and significant events, party officials organised lavish banquets. The launch celebration of DniproBud in October 1932 was impressive, coinciding with the onset of mass starvation deaths in the countryside. According to the memoirs of B. Weide (who worked in the personnel department at DniproBud): “…banquets lasted for two days in restaurants on the right and left banks. There was a large selection of dishes on the tables, as well as wine from Massandra’s cellars. … In the offices of the departments, there were tables with vodka, meat, and bread. Anyone could drink and eat as much as they wanted!” The invited officials were accommodated in hotels located on the left bank (the so-called old part) of Zaporizhzhia. There were three comfortable establishments for short-term accommodation of ‘workers’: “Intourist, the Zaporizhzhia Communal Hotel and the House of Collectivists.

From November 1932, the death toll from starvation in the Zaporizhzhia region became massive. Parents, primarily from the village areas, often brought their children to the city and left them in crowded places: at railway stations, markets, in the entrances of houses or at the doorsteps of nurseries and infant homes with the sole purpose of saving them from starvation. There are many testimonies to this in all the regions affected by the famine.

According to Ivan Vasylenko’s recollections, women were increasingly talking about the need to take their children to an orphanage: “The word “shelter” encouraged every mother. And some women did not know where their children were, in which “shelter”, or whether they themselves were alive, but they sighed with relief, hoping that their children were alive.” One of these “shelters” was located in the so-called “old part” of Zaporizhzhia. It was the central part of the city (then – Stalinskyi district).

According to Ivan Vasylenko’s recollections, women were increasingly talking about the need to take their children to an orphanage: “The word “shelter” encouraged every mother. And some women did not know where their children were, in which “shelter”, or whether they themselves were alive, but they sighed with relief, hoping that their children were alive.” One of these “shelters” was located in the so-called “old part” of Zaporizhzhia. It was the central part of the city (then – Stalinskyi district). The Intourist Hotel, a grocery store, and the City Food Store were located in the same quarter. Officials also lived nearby in comfortable houses. If we take into account family members, the total number of people in the city was tens of thousands. This was the wealthiest and best provided with food and basic necessities part of Zaporizhzhia’s population. It was in this place, in the centre of the welfare of the city’s Bolshevik leadership, that a real conveyor belt of child death was operating. In a year and a half, from May 1932 to November 1933, approximately 800 children aged 1 week to 7 years died within the walls of this orphanage (we wrote about the history of this notorious institution in our previous research).

Employees of the government agencies located around the baby’s home could not help but know about the mass deaths of children. However, local party functionaries, receiving food rations for their support, were unwilling to acknowledge the child pestilence. Similar situations of increasing infant mortality rates were observed throughout Ukraine.

In 1932-1933, Zaporizhzhia, like other cities of the Ukrainian SSR, was gripped by famine, bread queues, and was filled with vagrants and homeless people. Liudmyla Yehorchenko recalled that peasants who came to Zaporizhzhia in search of work or food often hid from the police in the basement of their houses and those of their neighbours’ ones.

In 1932-1933, the whole of Ukraine was in a state of famine. First of all, villages, cities, towns, and the capital. The Holodomor did not spare any settlement: there were numerous victims everywhere. Witness to the Holodomor of 1932-1933.

No less crucial today is the memorialisation of those who died during the tragedy of 1932-1933. In Zaporizhzhia, even the installation of a memorial plaque on the facade of the former infant’s home faced numerous obstacles for a long time. The first facts about children’s deaths became public in 1993. In 2013, a research study established that the number of victims in this orphanage was 788. The initiative community of Zaporizhzhia proposed to install a memorial sign on this building, but until the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, the city authorities had not granted permission. It was not a question of money: caring people raised the necessary resources, and the authorities only needed to give a permit. However, the pro-communist bureaucratic machine delayed this step for years. Nevertheless, human memory managed to overcome this obstacle as well. In the autumn of 2014, following the Revolution of Dignity, a memorial plaque was unveiled on the facade of building number 7 on Oleksandrivska Street (formerly known as 7 Rosa Luxemburg Street) to commemorate the children who lost their lives during the Holodomor of 1932-1933.

In November 2020, just before the anniversary of the Holodomor of 1932-1933, the plaque was vandalised and later restored. It is unclear if a detailed investigation was conducted or if the perpetrators were identified.

Inna Shuhaliova,

Senior researcher at the Department of Holodomor Research

and Man-Made Mass Famines at the

National Museum of the Holodomor Genocide

Source: Newspaper ‘Ridnyi Krai’.