Every day two or three people starved to death in our village | Voices of Holodomor witnesses

Anna Slobodian, née Kashchak, was a four-year-old kid from a peasant family in 1932-1933, when her village was hit by the Holodomor, the genocidal famine of Ukrainians by the Soviet authorities, which killed millions. She recollects how the Communist authorities confiscated all food, how people starved to death in her village, and how her family survived on dried fruit, mushrooms, and food surrogates. Her husband lost three siblings to the famine. This story is one of many eyewitness accounts gathered in the expeditions of the Holodomor Museum.

Collectivization , dekulakization , the Holodomor of 1932–1933—all these Soviet anti-farmer terror policies hit hard Anna Slobodian and her family.

Anna Slobodian was born in the Kashchak family of ordinary farmers. She witnessed how her father, a successful farmer, turned into a rightless member of a kolkhoz, the Soviet “collective farm” with its members being de-facto serfs. This transformation occurred in the spring of 1932, not long before the Holodomor man-made deadly famine hit Anna’s village.

Soviet authorities classified Anna’s father as “kulak” — a wealthy farmer

The events Anna Slobodian tells about unfolded in her village of Yanchyntsi (now Ivankivtsi, Khmelnytskyi Rayon, Khmelnytskyi Oblast) located in the Ukrainian historic region of Podillia. Propaganda of the Communist party’s “new order” permeated all spheres of life in Soviet times. Anna Slobodian’s native village got the name of Radianske (the Ukrainian word for “Soviet”), which was typical at that time as the communist authorities were renaming many streets, villages, and cities so that they sounded in a more Soviet way.

The Kashchaks were individual farmers, like the majority of Ukrainian villagers in the 1920s.

“They had a field, had their own horses. They were considered individual farmers, somehow like this they were considered,” Anna Slobodias says about her parents.

There were wealthier farmers in the village, who had mechanized farm machinery, for example, sowing machines, winnowers, threshers. Poorer fellow villagers owned their land but didn’t have draught animals or tractors, which is why they had to seek employment and do some hired work for other farmers. In return, their employers could provide them with access to the horses or machinery they needed.

“There were many such people who had neither horses nor carts nor sleighs – nothing. Then they assisted wealthier ones during harvesting to reap, to load those sheaves, to transport, and to thresh them. And these wealthier called “kurkuli” (better known by their Russian designation as kulaki, – Ed) would give them a cart or horses. But people supported each other. Helped each other, there were various ones,” Ms. Slobodian recollects.

The Soviets divided the farmers into three categories – the poor, middle, and rich peasants. Through agitation and propaganda, in every possible way, they played off these made-up strata against one another, antagonizing them. Authorities categorized Anna’s father Pavlo Kashchak as a wealthy farmer, for this category communists used their political and ideological label of “kulak.”

It didn’t come as a surprise that the private farms were labeled as “kulaks’” not only for economic reasons. This list was expanded by all those who had refused to support collectivization and continued to run their family farms by themselves.

“My father was told that he was a kulak. How on earth was he? He had horses, a cart, and a sleigh. And three children. But he was called that,” says Anna Slobodian indignantly.

Peasants believed the collectivization wouldn’t last long

The farmers of Podillia were indifferent to the collectivization as far as it was voluntary. They were leery of joining the collective farms. A common sentiment among the population was that “the Soviets weren’t there to stay.”

The owners of prosperous and “middle” farms stayed away from kolkhozes for a very long time. However, at the end of the 1920s, the Soviet government introduced the policy of forced “all-over collectivization,” which in practice ended in the destruction of the established ways of life of Ukrainian villagers.

”Every farmer thought it wasn’t a big deal, didn’t give up, thought it would change, but it didn’t… They’d beat the man, take everything away…” Anna Slobodian commented on that sentiment.

Individual farmers became unnecessary for the communist regime, and it started taking various economical and physical measures against them.

Villagers hand over their agricultural equipment over to the Kolkhoz named after the 13th Anniversary of October. Krusheltsi village of Vinnytsia region, 1931. source: Pshenychnyi Central State Cinema, Photo and Audio Archives.

In 1932, the Soviet “reforms” of the Ukrainian countryside reached the Kashchak family. Anna Slobodian remembers in detail everything that happened to her relatives during the two most remarkable days. The life of the large family changed forever, making the pre-kolkhoz past only a memory.

“They arrive, come — some four people, such strong, tall, handsome… and go directly to our barn. They took out the horses, tied them up and harnessed them to the cart. And then they started carrying the sacks. Because the man [father, – Author] distributed everything in the spring — something for sowing, something to feed his family until the next crops. The sacks with that grain still remained. And they started loading up these sacks,” Anna Slobodian tells how a so-called “towing brigade” came to her family and house.

Anna with her elder brother didn’t have an idea what was happening. Usually, when their father was harnessing the horses, they knew that they were about to go to their field with him. As they always did, they sprang up to sit on their cart, yet soon realized that the communist activists were cruel not only to adults,

“…but they grabbed us by the spine and flung us off that cart, these strangers. We struggle to get up, and they loaded the rest of the grain and flogged me and my brother with a whip,” Anna says.

In this situation, the father couldn’t protect his children, nor his farm. The family was left without a cow — the communists ignored even the fact that Sofiia Kashchak, Anna’s mother, was feeding her newborn son when they were driving the farm animals away.

On the next day, the brigade came back to finish their job. They took away all the farming tools — a plow and harrow — and brought them away to the kolkhoz. Then they started searching the house. In the oven, they found a bucket of wheat which the family prepared for baking bread. To the last grain, they poured it into their bag. They took away even the small bag of green peas, which the children picked on the previous day.

Anna was only four back then, but she realized that the “activists” were taking away the last food her family had.

“I grabbed that little bag, I wanted to take it back. He pulled and hit me, and the other man was gathering everything that was left on the stove, as another bucket was there. They smashed our millstones and went away. And that’s it, they had never come to us again,” Ms. Slobodian says.

Using their grain procurement plan, the communist totalitarian regime was conducting the genocide of Ukrainians. The “towing brigade” included communists, village activists, kolhoz members, and sometimes, they even engaged city students in this kind of work. They confiscated food, searching throughout the farm – in the house, in the garden, stable, cowshed, etc. Ukrainians knew that everything was to be taken away and their families would have nothing to eat. That’s why they tried to hide something. According to Anna Slobodian, the “towing brigade” usually managed to find the stash sites,

“Even when someone happened to bury a sack or something, they fetched such an iron thing and “beaked” everything with it, finding and taking all away.”

The authorities “pumped out” grain not only from wealthy farmers but even from those Ukrainians who were among the first to join the kolkhozes.

“No matter kulaks or not, they snatched everything anyway. They took away whatever people had. And the cooked dishes… And may you live on. We had to survive these two years, how to survive?” Ms. Slobodian says.

The regime strived to destroy Ukrainians as a distinctive nation as those resisted the Moscow policies openly opposing the Soviets and seeking to reinstate a country of their own.

Grain procurement Komsomol brigade from Obukhiv. Reproduction from the album “From the history of Komsomol in Obukhiv.” Obukhiv village of Kyiv okrug. 1930. Photo: Pshenychnyi Central State Cinema, Photo and Audio Archives.

Dried fruit helped Anna’s family survive the winter

After the confiscations of their foodstuffs, the Kashchaks left only with four sheaves of wheat, hid by Anna’s father in the yard under the hay they had stored for cattle. However, the wheat didn’t last long, and the family soon started eating surrogate food. The parents were sending their children to gather various plants, such as nettles, orach, and horse sorrel.

When the wheat began to ripen, children frequented the field to pluck ripe enough grains one by one and bring them home to the adults. Under Soviet laws of the time, it was a criminal act.

“So then my brother and I went there to do stealing. As we go there, we have knives and cut those ears of grain, cut them, he puts them to his bag, I to mine,” Anna Slobodian recalls.

The communist activists destroyed the family’s millstones during the searches, leaving the Kashchaks without their tools for grinding grain and food surrogates. Milling grain secretly was a punishable crime under the “Five Ears of Grain Law” of 7 August 1932.

To grind the grain without their millstones, Anna’s father first crushed the wheat with a wooden pestle to have it later added to some orach or nettle pottage. Later he also made a wooden mortar.

“Whoever had something used what they had — found a piece of iron, then used it for crushing, it was faster. And my father had some wood, he used some wooden scoop. If the grain was dry, some whole grains would still remain after the crushing… we would gather some grass. And they would pour there that broth with the chopped grass and that was it,” Anna says.

This is the way the Kashchaks family struggled to make ends meet.

Millstones

The collective farm’s fields were guarded. The crops of potatoes and beetroots remained unharvested that year.

“They kept watch of the field, driving people off by shooting above their heads. And didn’t allow to… And this is how that harvest rotted,” Anna recalls.

The harvested wheat was taken to the nearby town of Derazhnia, where they stored it in sacks for a long time. According to the witness, the grain got rotten because it remained outdoors open to elements in winter. Meanwhile, starving Ukrainian farmers died every day in Yanchyntsi and other villages.

There was a forest near Yanchyntsi, so the Kashchak family as all other fellow villagers of theirs took advantage of the opportunity to pick mushrooms there in the fall. Amid the mass starvation, they gathered and consumed everything they could find, and the cases of food poisoning became frequent.

“We would go, pick and clean them, and my mother would rinse them, wash them… She’d put them in a pot, set it to the embers to boil them. If there is some flour to add, it would be like grout, because it was rough, if none, we would eat it as is,” recalls Anna Slobodian.

They used to go into the woods as long as they had enough strength, and when the people’s legs got swollen, it was no longer possible for them to pick mushrooms.

Anna’s father Pavlo Kashchak had a Jewish friend in the city, who was in trade. He helped to get food in 1932–1933. The Kashchaks had a big orchard with apple, pear, and plum trees. This man used to visit them on his cart to pick up fruit for sale in the city. In return, he brought them some groats, flour, and sugar. The family dried the fruit that remained and then cooked them in the winter when they could no longer gather herbs or get anything else edible. It was their garden that saved the family, says Anna Slobodian,

“And my father would dry the fruit up to cook it in a pot in winter. What could you get in the winter? There was neither orach nor nettle. Then they cook that oxalis, pears, plums, everything. If only they had something to add, it would be like a grout. There was nothing. We eat it as it is.”

The villagers didn’t even have salt left to season the so-called balanda or other surrogate stew. One day a rumor spread in the village that there was some accident in Derazhnia in which salt was spilled in the street. Some villagers rushed to the city, hoping to get at least a handful of salt. But instead, those salt-seekers were detained and locked out in a barn.

Dry apples

“They remained in custody for three days. No water, no food. They were released, beaten, and they came home crying. And that like that, this is we used to live in those two years,” Anna Slobodian retells a story that she had hers from her parents.

Everyone in the village was starving, that’s why it was not always possible to get even surrogates.

“If you go out late, you won’t pick up that nettle or dock or orach, you won’t get it, because everyone rushed there.”

The communist totalitarian regime used its most brutal weapon against Ukrainians, the man-made famine. After their long-lasting starvation, people quit caring for their spiritual, political, and cultural needs. They fully focused on the most basic need, food.

“We cried every day because we wanted to eat, we didn’t think of anything else. But as soon as the apples appear, we’d be like heroes. We already had such big bellies, our heads became a little bigger,” Anna Slobodian recalls.

Every day saw deaths of starvation among villagers

Every single day two or three people died in the village of Yanchyntsi in the worst days of the Holodomor. The neighboring Pasternak family had only two children left alive out of seven as five others died of starvation. Other neighbors lost six children. The Holodomor did not pass without losses for the Kashchak family as well—Anna’s grandfather Viktor died, her father’s sisters Nastia and Palazhka swelled from starvation, but somehow survived.

People buried their fellow villagers in large mass graves without any coffins and funeral rites.

“If a child died, they carried it out, and sometimes a person would carry two bodies wrapped in some cloth to the pit. And it was how they were burying those people. Well, many died,” she says.

Mass graves of the Holodomor victims were almost in every village, near cities, near railway stations. However, the Soviet authorities denied and falsified any data on the genocide. The Holodomor graves were often razed to the ground, built over, or simply just left without any signs of graves.

In 1934, starving Ukrainians who had survived were forced to work in collective farms.

“They started hounding those who remained – they had taken away their horses, their cattle. But who was to take care of the cattle? It is, as they say, alive. So some did this work,” Anna Slobodian recalls.

Only two of five children in the family of Anna Slobodian’s husband survived the Holodomor

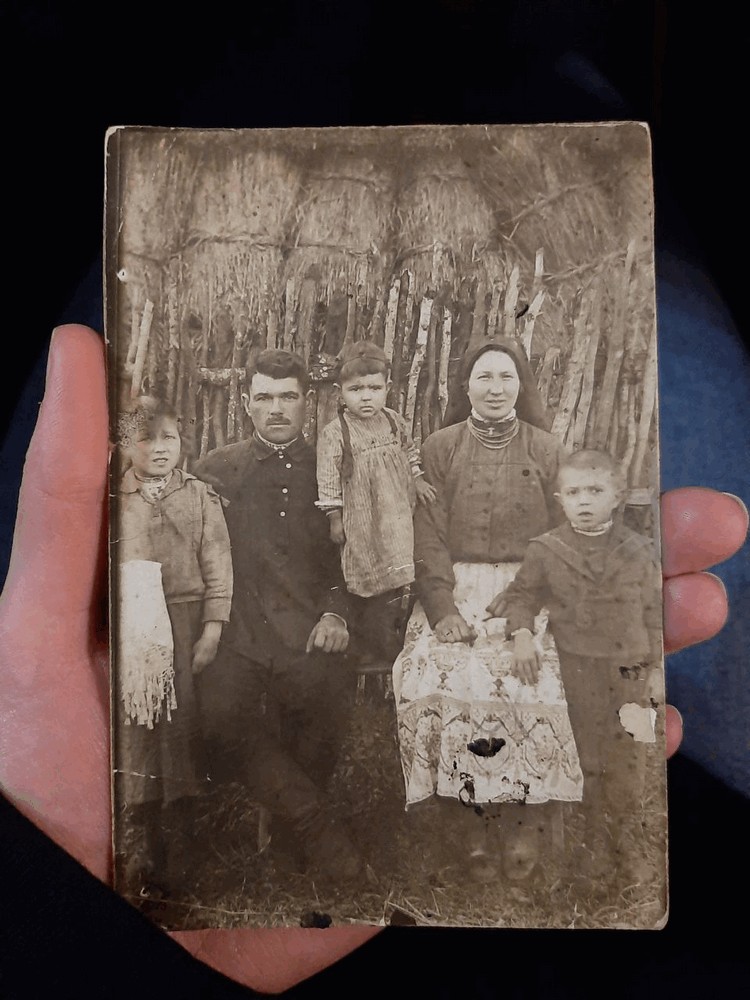

Ivan Slobodian, Anna’s husband, also witnessed the genocide of the Ukrainian nation. As a child, he lived in the neighboring village of Ziankivtsi. His father Roman Slobodian and mother Feodosiia had five children, but not all of them survived the Holodomor. Three of his children — Vasyl, Serhii, and Antonina — died of starvation. A photograph of 1932 showing his family posing in front of the harvested wheat is kept in the Slobodian family archive.

The Slobodian family photo of 1932 showing the parents with three of their five children(left to right): Mariia, father Roman, Antonina, mother Feodosiia, and Ivan.

1946-1947 famine diet: “doughnuts” from frozen potatoes

Those who survived the Holodomor and World War II hoped for a better life, but the mass artificial famine of 1946–1947 awaited them in the early post-war years.

“I went for rotten potatoes in the spring, which remained outdoors in the fall and froze. I’d go and pick them up, I’d collect them and then peel a bucket of them… I used to go to distant fields, I was there in Yablunytsia. And there were kahats … So I went there… for those rotten potatoes because we already had eaten up all potatoes from our fields,” Anna Slobodian tells her survival story of the 1947 spring.

Out of the frost-damaged potatoes, people were baking dry “biscuits,” which saved them during the famine. Anna Slobodian recalled how she was cooking this dish,

“And it would freeze, freeze during the winter. And it is so whitish, just like nothing but starch. And I remove the peels… put it in the bowl, salted it with a little bit of salt. And you don’t need to add any butter, it doesn’t stick as if it was greased. And such ‘doughnuts’ were good, they were very good.”

Ukrainians who survived the Holodomor and saw their loved ones dying of starvation have been deeply traumatized emotionally and mentally for many years. Anna Slobodian describes her emotional condition in the following years,

“I arrived here in 1950 and still couldn’t eat my full.”

Throughout the Soviet era, Ukrainians couldn’t tell freely about the Holodomor and share their trauma experiences.

“There were such famines. Such famines… God, when I recall them, I don’t know what is happening to me, but I get up trembling. But how did we survive? How did we survive having nothing to eat? You see, God gave us it all, or what? I don’t know,” 93-year-old Anna Slobodian ponders.

Interviewing Anna Slobodian, the Holodomor survivor and witness.

Only after Ukraine regained its independence in 1991, the crimes of the communist totalitarian regime came under the limelight of public discussions. Ukrainians continue to disseminate the truth about the Holodomor to this day.

Anna Slobodian’s story was recorded in an expedition to the village of Ziankivtsi as part of the project “Holodomor: Mosaics of History. Unknown Pages,” supported by the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation.