“Everything was taken away by men in black leather jackets”: an impressive story from the envelope

“The famine for the poor never ended. There was a famine throughout the 1930s, before the war, and during the war from 1941 to 1945. In 1947, there was a terrible drought, followed by famine.”

These are lines from a letter sent to the Holodomor Museum from the Luhansk region. 92-year-old Lidia Antonivna Tykha wrote to us from the city of Severodonetsk. Dated back in 2020, she saw in Kraina magazine a call for all those who survived the Holodomor of 1932-1933 to share their memories.

Lidia Antonivna spent a long time thinking about writing about her suffering childhood. After writing them on paper, she addressed an envelope to “Kyiv, Holodomor Museum, Museum Managers” and sent a letter. However, it returned with the note “incorrect address.” But the author did not give up. “I even wanted to send a letter to the Kyiv City Hall – “and they will sort it out.” We don’t know who eventually helped the woman find the correct coordinates, but we have got a letter. And we are grateful to everyone involved who helped it get to the museum. And especially to the author Lidia Tykha, who wrote down her testimonies, which are so valuable for history, and shared them with us.

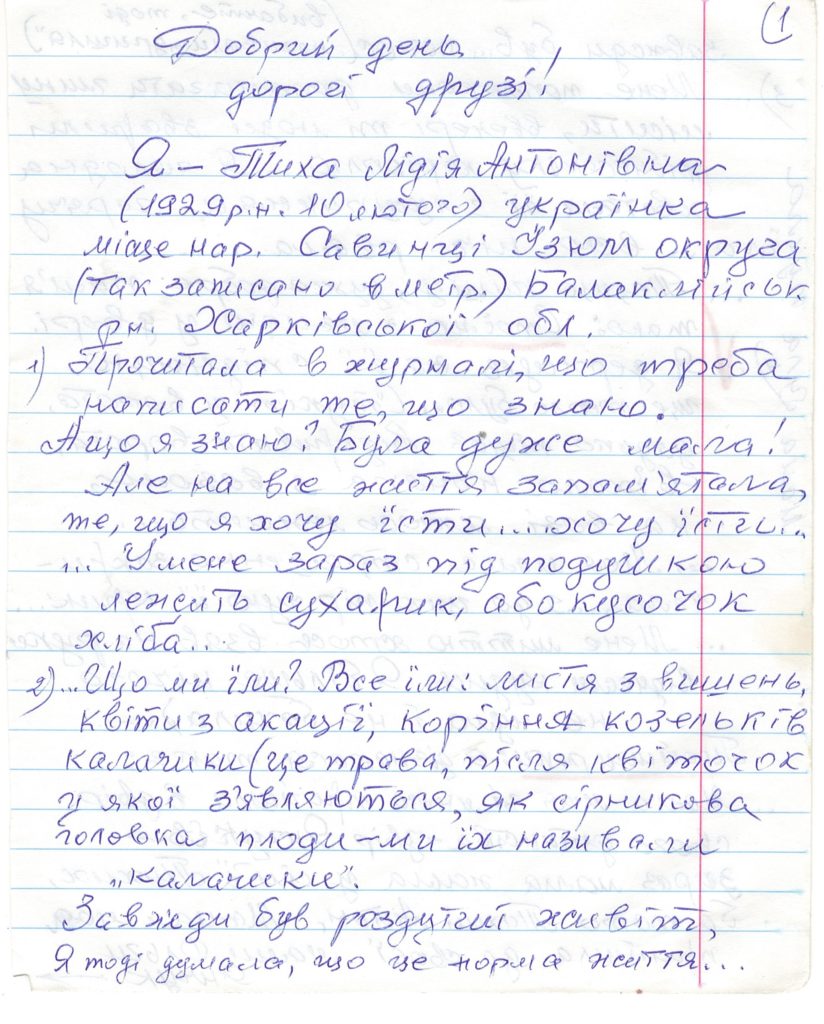

“I still have a cracker under my pillow”

Mrs. Lidia was born on February 10, 1929, in the village of Savyntsi, Izium District (as recorded in the metrics of the woman, now – Balaklia district in Kharkiv region).

And although I was very young, “I remembered for the rest of my life that I wanted to eat – I want to eat.” “I still have a cracker or a piece of bread under my pillow,” the eyewitness wrote. “What did we eat?” Everyone ate: cherry leaves, acacia flowers, goat roots, flowers. My stomach was always bloated; I thought it was the norm then. I always had diarrhea…

They once asked me to help knead the clay, and those people cooked small potatoes in the evening. Being hungry, I grabbed it hot and ate it. Then I was vomiting all night. “

A young child’s memory recalls: “We were standing with my mother in the yard. I was holding on to her skirt. It was still warm. Knock on the gate. A man went to open the gate. A horse with the carriage came, and someone was lying in the carriage… My mother screamed terribly, and I can still hear her screaming. I was immediately picked up by someone and taken away. I heard and saw nothing more. Years passed. I found out the following: my mother came to the yard of her childhood – the yard of the Yanchuks, to the mother of Olga Yanchuk. Grandmother went to gather ears of grain in the field where grain had already been harvested. She collected a whole sleeve of ears of grain. She was caught by a whip driver and taken to the tyrlo – the name of the place where the big scales were. There was a big weight. They hit my grandmother in the chest with that weight, so she fell and turned blue. While they got the carriage, while they brought her, she turned black. “ Thus, a handful of spikelets in an already threshed field cost the life of Lida’s grandmother, Olia…

My father’s family was dekulakized. Lidia Antonivna writes that grandfather Fedot (father’s father) was in captivity in Germany – “he had been a slave for ten years.” When he returned, the farm fell into disrepair. He raised it with his hard work. Then his son Anton married, and the family had two children, Ivan and Lida.

” We lived in my grandfather’s house. Then we were all kicked out, and everything was taken away. We were staying at other people’s fences, being hungry and cold,” the woman writes. – “My mother managed to take away her property – she took the pillows to strangers in the barn. And then she rushed in, and those people ripped open the pillows and stole the feathers from the pillows. Towels were stolen, my mother had a beautiful dowry. My mother was a hard worker, so she knew how to do everything: sew, embroider, weed the garden, and milk the cow… Everything was taken away by men in black leather jackets.”

“The Church did not want to obey the Basurmans”

In the center of Savynets stood, as the author writes, “a beautiful church.” “How beautiful it was! Icons… My grandmother Oleksandra Dmytrivna, Anton’s father’s mother, took me to church several times,” Ms. Lidia recalls. For the rest of her life, she remembered how the temple was broken into: “Many cars came, I, as a child, did not know what they called. I only knew the word “tractor.”And these tractors from acceleration in walls hit, hit, and so many times. And the wide walls, painted blue, did not obey the Basurmans. Such a “miracle,” the woman recalls, lasted a week, and then the church fell under the onslaught of atheists. “We, the children, collected the ornaments that were thrown from the walls – bay leaves, painted in gold. I brought them to my grandmother. She was sitting, spinning on the press. Tears rolled down her cheeks. She, an old illiterate woman, just said, “Damn raklo.” May the earth be soft as swan’s-down for her…” (“Raklo” is a Ukrainian vulgar word borrowed from German, common in Kharkiv and Poltava regions, which means: swindler, bastard, thief, “petty criminal from the village”).

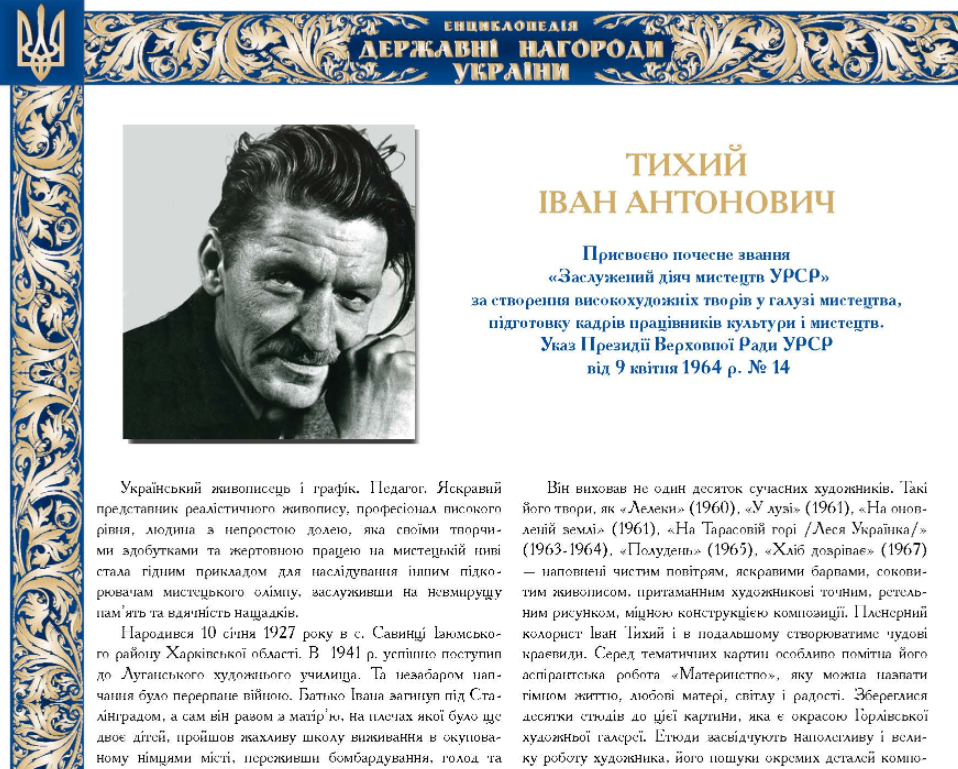

In the photo: Ivan Tykhy. Church in Sedniv. 1974

Instead of the destroyed church in Savyntsi, wooden tables and long benches were set up. Collective farmers, who worked in the fields from morning till night, used to eat there. “My brother and I went to look for our mother, she had already been driven to the field (so everyone said ” drove,” did not walk, did not go, but drove because people did not want to go to work on the kolkhoz,” -emphasizes Lidia Antonivna.”We went to the field with my brother – the fields had already been harvested. We dug the ground with sticks, looking for either potatoes or onions. I found the onion, chewed it, and it burned my cheeks. Brother Vania says: “Pat your cheeks with your palms – there will be a breeze, and they won’t burn like that! .. I see and hear all this as if it were yesterday.”

“On one foot – a boot with a tied sole, on the other – a felt boot with patches”

“After the dekulakization, “social winds” threw us to Donbas, to Sentianivka. My grandmother, my father’s mother, cried for the land in Savintsy until her death (in 1960).”

In 1940, another sister was born in the family-Musia (Tykha Maria Antonovna). She didn’t have a luck to know her father, to have at least some memories of him. After all, she was very young when he was sent to war in 1941. He never returned home. “My father Tykhyi Anton Fedotovich, born in 1904, faithful to the military oath in battle, came to Stalingrad, died there, and was buried there. He was recorded in the book “Memory,” Volume 15, Luhansk region, p. 418 .»

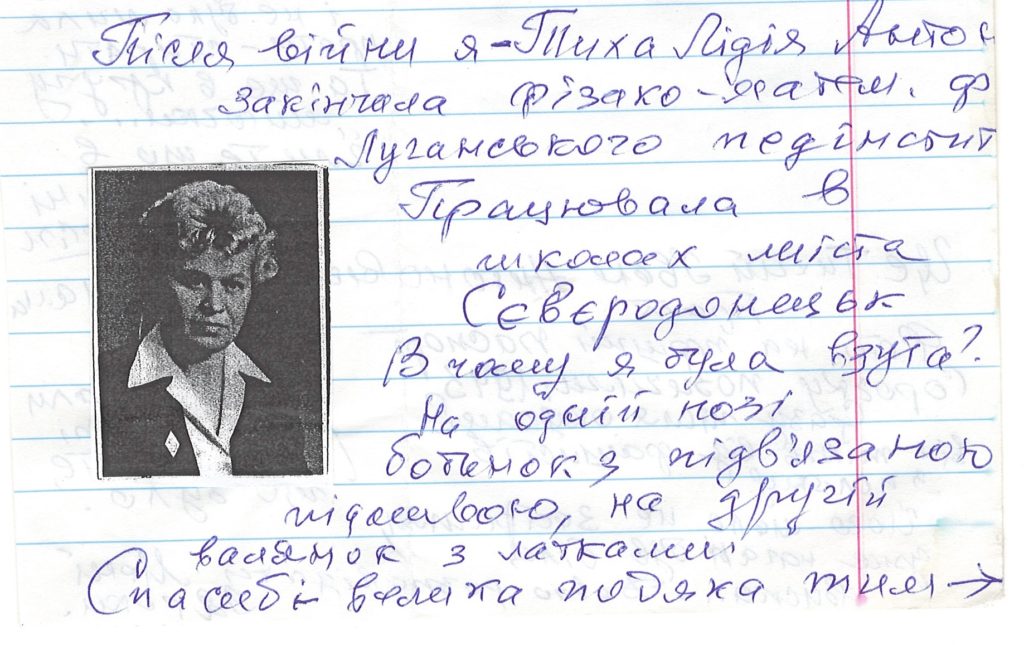

In the postwar years, the mother herself had to bring up three children. However, all grew up worthy people and received an education. “After the war, I graduated from the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Luhansk Pedagogical Institute,” the woman wrote. – What was I wearing? On one foot – a boot with a tied sole, on the other – a felt boot with patches. Many thanks to those people, who surrounded me, because no one mocked, no one laughed. At the institute, being poorly dressed, I got instructions to fill in diplomas. I had good handwriting, and no one in the group knew Ukrainian fluently. “

After graduating from the institute, Lidia Tykha worked in schools in Severodonetsk. “I used to work for 38 years, honestly teaching mathematics and physics since 1951. I’m not ashamed to walk down the street and meet students now. “

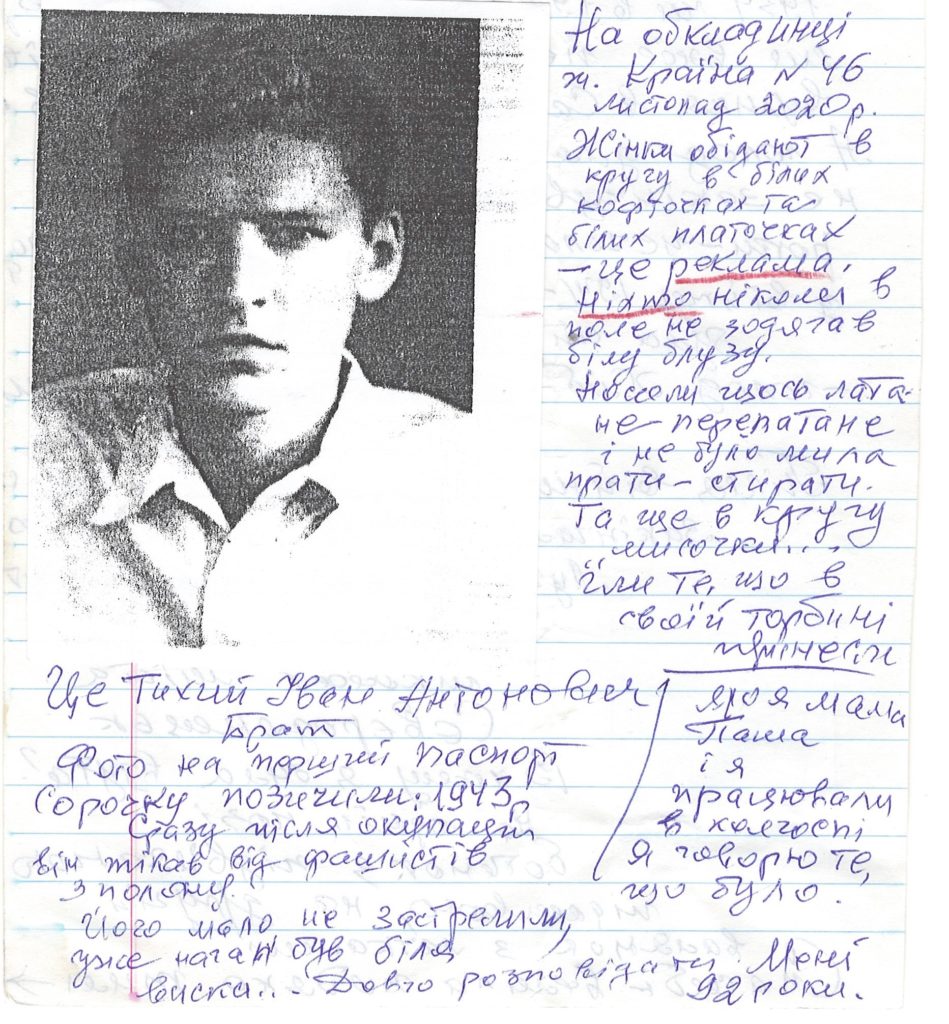

“My brother Ivan Antonovych Tykhyi (1927-1982, a painter, Honored Artist, Associate Professor of Painting at the Art Institute of Kyiv (now the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture). He is recorded in the encyclopedic dictionary “Artists of Ukraine” (also a record of the artist is in Wikipedia. – M.). My brother did not receive the title People’s Artist of Ukraine because he was in the occupied territories. Although the Higher Attestation Commission made such a proposal, appreciating his work, “said Ms. Lidia. According to her, in the museum of the city of Balakleia, employees collect materials about their compatriot Ivan Antonovych Tykhyi.

Lidia Antonivna also put photocopies of her and her brother’s photos in adulthood in the envelope. “There were no photos of those years, neither dad, nor mother, nor us, children,” she wrote. It was not up to the photos because “there was nothing to buy a wick in the lamp.” And her brother had to borrow a shirt to be photographed on his first passport.

Ms. Lidia writes that being a bit older, she tried to find out more about the Holodomor. ” My father Anton did not allow my mother to say anything so as not to go to Siberia for chattering. And as an adult, I tried to ask my mother everything, but she only shed bitter tears “…

Deprived of property, land, bread, and ultimately dignity, the witnesses of the experience today speak for themselves and for those ones who in 1932-1933 deprived of the most valuable thing – life. Every memory is significant. Write to us if you are a witness to the Holodomor. Write to us if your relative is an eyewitness to those events.

Let’s create the Holodomor Museum together!

Our address:

National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, st. Lavrska, 3, Kyiv, 01015

E-mail address: