“I have no wish remain. I saw this paradise.” What engineer Jerry Berman wrote about from famine-stricken Ukraine

“Do not believe in the paradise here and do not believe one word of the beautiful speeches you read in the papers I send you!My word of honour!…God! If I could tell you of the night scenes I saw… No one of you can visualize a huge potato-peel rubbish heap mixed with dirt, snow & sand outside a Russian Stolovaia [works canteen]. But, think and imagine four workmen on this bridge caught by me squatting down on this heap in darkness of night at 3.00 am and feeling about this heap for bits of potato peel to “feed” their wives and children!”

This is an excerpt from a letter from the South African engineer Jerry Berman, written in February 1933 from Stanytsia Luhanska to his relatives outside the USSR. Almost 90 years later, these letters will return to Ukraine again, but as exhibits and crucial evidence of the crime the Stalinist regime committed against Ukrainians in 1932-1933.

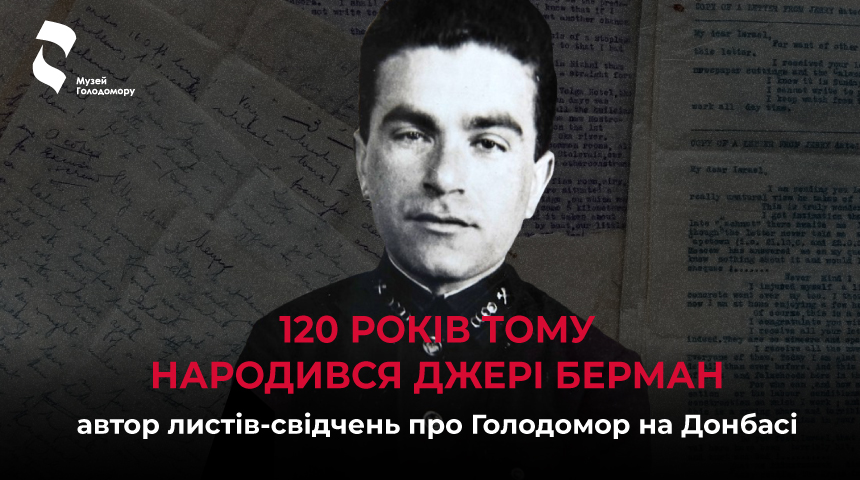

February 16 marks the 120th anniversary of Berman’s birthday. And therefore, there is a reason to remember him and his shocking observations, which he left us, writing ordinary letters to his relatives by the light of a dim candle.

Letters from the attic

2016, United Kingdom, Manchester. While cleaning the attic of her house, the Englishwoman Alison Marshall finds a stack of letters addressed to her grandfather Meyer Fortes. The woman is not aware of their historical value. After all, she knows nothing about the Holodomor in Ukraine and cannot find out which events are described on sheets of old paper.

“I showed the letters to different people, but no one could explain what they were about,” Ms Marshall says.

Someone else might not bother with some old epistles and throw them in the rubbish bin. But Alison Marshall, a scholar herself, was struck by the letters.

Not an easy search lasting several years began. Marshall read the letters and learned more and more about Jerry Berman.

“I found his son Peter, who helped establish some facts of his father’s biography, and also learned more about the historical period that Gerry described. I learned from the letters that he was born into a Jewish family in Lithuania, which was part of the Russian Empire at that time. Life was difficult, so the family had to emigrate to South Africa. Jerry was then 17 years old. While studying at the University of Cape Town, Jerry met my grandfather Meyer Foster, to whom he later wrote his letters.”

And then fate brought Alison to the artist and teacher at the University of Huddersfield Sara Nesteruk, who has Ukrainian roots. She helped Ms Marshall finally understand the historical value of the old letters and advised her to transfer them to Ukraine, to the Holodomor Museum. So Alison Marshall did that in the summer of 2021.

Fortunately for us, the letters were perfectly preserved. Most of them are typewritten. No, Jerry himself, while working in Soviet Ukraine, had neither a typewriter nor the opportunity to print his messages because he often could not even find the good paper (therefore, he sometimes replied on the back of the letters he received from relatives).

But Jerry had three brothers, a sister and a best friend. He could not write to all of them separately, so he asked his brother Israel, who lived in the city of Tzaneen (South Africa), to make copies of the letters and send them to others.

Thus, letters addressed to Israel flew to other cities and corners of the world: Esther and Aaron in Cape Town, Leivi in New York, and Meyer Fortes in London.

To a socialist paradise for work

How and why did Jerry Berman end up in the USSR? After graduating from the University of Cape Town, he became a bridge engineer. The work didn’t work out. First, searching for work he went to New York, where his brother Levi lived. In the USA, a great depression had already begun, and it was not possible to find a job there.

Meanwhile, rumours spread around the world about how rapidly the USSR was developing. The country, covered by forced industrialization, needed qualified personnel: engineers and specialists who could work on foreign equipment, which the government purchased in large quantities for Soviet factories.

Many, especially young people, admired the Soviet Union and romanticized everything that happened there. So 29-year-old Berman, having read in the newspapers that the USSR needed engineers, went there. And in 1932 he found himself in Donbas, on the construction of a bridge in Stanytsia Luhansk.

That bridge across the Siverskyi Donets, built by Berman in 1933, has not survived to this day, it was blown up by the Red Army during the retreat in 1942. Photo from the State Archives of Italy in Rome

But very soon, the romance disappeared under the influence of terrible realities. What Jerry saw in the UkrSSR horrified him. Terror, coercion, fear and slave labour supported the Soviet utopia.

“How can a foreman work and stroke two boilers working eight hours and getting for his labour 800 gr. black bread and money to buy in a filthy-stable-stable-like (worse than Native African Eating Rooms) Stolovaia a plate of cabbage soup – meatless – and two spoonfuls of “porridge”(?) “Kasha”!!!” – Jerry write to his brother Israel – What is the result?… People sleep while at work, people curse everyone! people grumble, shout and curse! Nerves are draw to a pitch of collapse!…”

Berman does not hide the fact that he got into a complete horror that defies common sense.

“6 horses died out of 17 due to rotten hay. Here at the moment the horse is more important than the man. People to keep themselves alive steal from their horses’ rations, especially mealies etc.”

In his letters, Jerry tells details that only a direct participant in the events can know.

Berman writes that being a foreigner has certain privileges, such as a lunch without a queue, which is more filling than others. So his situation is a little better.

“I get the the [privileged] dinner here, which only the workers of the Caissons under compressed air of 2-3 atmospheres get; I fail to see how they survive. Soup of sour cucumbers and nothing else. (All workers get the same) and then the second dish is mashed potato with a tiny bit of meat! This is the privileged part, for the other get no meat!.. This is as true as I am here! Say it and tell it to all your Communist friends and let anyone deny it! On such semi-alive men is being built successfully (?) the Five Years Plan!….”

Hungry people are not able to work well, states Jerry. And the Soviet leadership also demands to fine workers for allegedly poor work.

“How can they be fined?? What can be taken from them! Only their “chains” of slave labour!” – the foreigner is indignant.

As a foreman, he has to deal with organizational issues a lot.

“Here the work of the engineer is not to build as much as to feed, [clothe] and house the men —-. And so all these three things are pretty difficult to perform, my lot as “Prorab” [supervisor] is unenviable! “

Everything has to be obtained and “knocked out” of officials – from bread cards for workers to building materials.

“The work itself is very interesting as you yourself can gather, only under Russian conditions of bad supply, of materials and labour one often goes crazy in trying to make things fit! —“

“People are going crazy! Bread is everything, and there is not enough of it”

The engineer’s letters disprove the popular belief that only the village was starving. The fate of the workers was no better: real slave labour for a piece of black bread. An acute shortage of food, a humiliating card system, empty shops, high prices – these are the realities faced by an engineer in Ukraine.

“People work here for bread only, the 800 gr. – 600 – 400 grms of bread daily, for no other food is obtainable from the stores. – There are none. Can a human being be it Russian (At that time, Ukraine and the entire USSR were identified with Russia. – Auth.) or anyone else feed himself and his family on 800 grammes of black bread and nothing else!…”

“It is inadvisable to carry with one more than one day’s bread ration. A whole loaf of bread that you may get perhaps for several days would cause such an event, that all passersby would stop and look at you. That is black bread. I can safely say that my life would be in great danger if I were to be seen in possession of merely one slice of white bread. Such a thing has not been seen here since 1928. Here on a wheat growing area!—”

But in collective farms, as Berman recalls, there is not even bread:

“Every kolkhoz is starving, it does not have a single piece of bread!… The workers of the kolkhoz do not receive bread”

“I feel like packing & going away. Bread I have not received for 3 days. Yesterday I was away in “Stanitza” & before yesterday there was a shortage. There is a terror of a cry. Men go crazy! Understand. Bread – that is all – & that is missing. Black, sour, badly baked. In 1932 we get nothing on our “Kartochki”

One day, Berman finds himself on a business trip in Kharkiv. He shares what he saw in a letter to his relatives:

“I saw a sight that only Beile has seen before… It was a bread line at Store No 48 on Engels street!I have seen many lines here, but this one never before. It was one deep, guarded by Militia men along its entire length of some four street blocks! Why?. – here you are.The province of Kharkov has just (very late!!) carried out its bread tax and is allowed to trade in bread. Here you are! You have bread on commercial prices, 15 times that of standard state prices, but 7 times cheaper than the forbidden trade with bread on the market! People took their places at midnight yesterday and herring like stood patiently all morning today. Interesting faces, these women with infants, strained faces these are. Very interesting! I stayed there a good half of hour! The militia men endeavouring to maintain order, hit those that try to get in without the line! On the whole you have about 30 militiamen doing no useful work, let alone those in the queue! A very low productivity of labour, this is!—Of those in the queue, one half or more are from the villages, where bread shortage is worse than in the towns!”

Several times in his letters, he mentions the city, which is on everyone’s lips today:

“I just received news from “Artomvsk” i.e. late “Bachmut” that 10. Dollars await me there in the Torgsin Store. Apparently from Leivi, although he never wrote about it.But to get to “Bachmut” and back, I need with the present state of Railway services 3 days and this I cannot get at the moment. We are too busy. Shall get it later on, perhaps.”

“It cost in human victims and money twice and more that it would have in America on similar jobs.”

Jerry realizes that he has found himself at the epicentre of a terrible economic experiment arranged by Stalin. Soviet construction is a show, a beautiful picture for Western countries, behind the scenes of which ugly realities remain. Human lives in this pursuit are expendable and nothing more. But the worst thing is that there is often no economic expediency in such forcing of events.

“Russia has made these five last years colossal blunders, blunders that are responsible for the semi-starvation that exists. Russia has gone in for a huge construction plan. Here was a political point, viz. to “show” what Socialism can do!!…..Take as an example. In five years they build on the Dnieper a Dam and a huge 1500 meter bridge near “Ekaterinaslav”. They built these in good record time. There is no doubt it! But what of the means!… It cost in human victims and money twice and more that it would have in America on similar jobs.”

The engineer adds that “the plants completed a year ago have not yet produced anything,” and the equipment purchased for Ukrainian bread and coal has not produced anything because it has not been put into operation. The colossal sacrifices with which the construction is carried out are in vain. And this is very depressing for Jerry.

“Russia built and built and got nothing for its building. It built and sank millions of resources into factories for steel and iron. Sank machines for which it sent out its bread and coal and oil and all the time these factories did nothing. How can you carry on? Imagine you sink money into your farm and sink and sink and sink and sink…”

“There are lies in your press, many lies, but these here are far greater!….Do you feel, Israel, that my political ideals before my arrival here have been terribly hit, and I feel terribly disappointed and hurt and bad!……….What a disillusionment, Eh!!!……”

“I cannot see people starving,” he admits in one of his letters. Therefore, he constantly tries to move from Ukraine to Russia, where, according to rumours, the security is much better.\

In May 1933, Berman finally succeeded, ending up in Nizhny Novgorod. There, according to Jerry’s observations, the food situation was much better. As a foreigner, he generally found himself in a privileged position.

“I get my food supplies at the Foreign Store “Insnab”. I am getting there more than one can use. I get everything that they have. Bread and sausages, sugar, nuts, cigarettes, raisins, biscuits, milk, butter etc. etc. It is simply unbelievable in Russia.This places me in a special category of human beings. I am the envy of all Russians, the envy of all.”

“I am well provided for but only me.” he writes in the letter. “My immediate superior – the “prorab” gets 425 roubles a month. I get as you know 400 roubles. He has a wife and two children, one of whom is an infant 14 month old. His monthly deductions are 80 roubles (income tax, loan subscription, culture deductions etc). That leaves 345 roubles. He buys daily one litre of milk for his child, that 2p50 or 3 руб i.e 80 roubles a month. That leaves 265. The Stolovia wherein he alone gets one daily meal of two courses (soup + kasha) charges 1p50 – 2p50 a day. That leaves 200 roubles a month. His “паек” that he gets in a centralized way is merely 800 gr bread for self + 1 klg for his family. The rest, as all here, must be bought at the market at market prices. Can you imagine how four people live?? – And that is a man of high position and responsibilities, who get a good specialist`s wage. And what of the workman who gets not 425, but only 130-180 roubles a month in all? [Or] the clerk, that gets 175-250 roubles and the inspector with his 220-260 a month?

I am the happiest of workers here for to me all this “beautiful” description does not apply. I am drawing, true, only 400 roubles a month, but I draw my foodstaffs from the foreigners` store. Milk there is 1 rouble a litre; butter 7 roubles a litre and not 50 as on the market; sugar 2 roubles a klg and not 70 roubles etc etc etc. My 400 roubles plus the store equals 4000 roubles without the store.”

Berman’s letters have a specific value in these everyday details. After all, official documents do not give a complete picture of the level of wages and prices at that time. And Jerry’s descriptions make it possible to understand the real state of affairs. He mentions that a cleaner’s salary is 50 rubles a month, and a chicken at the bazaar costs 60 rubles. That is, the monthly salary is not enough even for one chicken!

“Slowly, but we are building on starving workmen. On the blood and sweat of starving men. On labour “free”, “convict”, compulsory and military. No, my, Russian life you will never understand. A paradox too great.”

“I am feeling fully disappointed with everything here, with the Social order, with the people, their manners, and their relations to one another, etc. I feel disgusted.”

“I have no wish remain. I saw this paradise.”

Instead of an epilogue

After all, “having built socialism”, in 1935 Jerry Berman returned to South Africa.

In the 1940s, he got married. In 1947, his son Peter was born.

At home, the former worker from Stanytsia Luhanska managed to make a successful career: he headed the construction department in one of the ministries, managing the construction of bridges and roads until his retirement in the late 1960s.

Berman died in 1979 in Cape Town without ever learning what valuable evidence he had left about the Holodomor in Donbas.

Subsequently, the history of industrialization was rewritten, and the role of foreign specialists such as Jerry Berman was completely “forgotten”, assigning all the laurels of the “genius builder” to the Soviet dictator Stalin.

Russia today continues to return Soviet myths and whitewash Joseph Stalin, who was only effective at one thing – the extermination of millions of people.

So Berman’s letters are an important contribution to spreading knowledge and truth about the Holodomor and the real cost of Stalinist industrialization.

Today, Stalin’s case is successfully continued by Putin. That became possible because the crimes of the communist regime were not condemned, in particular. After all, Russia itself did not want to look at them with the eyes of truth.

Recently, all of Jerry Berman’s letters (almost 70 of them) have been digitized and published on the website of the Holodomor Museum. Anyone interested in the past of Ukraine and the Holodomor, in particular, can learn about them. By clicking on any of them, you will open a scanned copy, as well as receive its transcription in English and a translation in Ukrainian.

You can find the correspondence on the museum’s website in the Holodomor/Archive/Jerry Berman’s letters section.

Lina TESLENKO

Source – Novynarnia