“Mother and grandmother died on the same day.” The story of Antonina Boravika from Latvia

This story is impressive already because of how it got to us. In 2010, Linda Austere, a resident of Latvia, heard the life story of her grandmother Antonina, who was born in the Vinnytsia region in Ukraine. Then, the young woman learned for the first time about the Holodomor of 1933-1932, about which she had known nothing before. Grandma’s story impressed Linda so much that she decided to record it on a dictaphone. Two years later, in 2012, Antonina Boravika passed away. But the audio recording remained, which became museum history ten years later.

Later, fate threw Linda Austere to Ukraine – the young woman worked here for some time. In Kyiv, she learned about the Holodomor Museum, visited it, and flipped through the National Book of Memory. But she never found neither mention of her grandmother’s family nor her native village of Dubrovyntsi. It disappeared from the map of Ukraine a long time ago and does not exist today.

When a full-scale war started, and Ukraine was the focus of the world’s attention, Linda Austere recalled a recording of her grandmother’s story. After all, the parallels between past and present events were obvious. The woman was sure that the testimony about the extermination of Ukrainians by hunger was crucial and should be in the museum. So in the autumn, Ms Linda wrote to us and then forwarded an audio recording of Grandma’s story. “My grandmother has passed away, her family was destroyed, of which there is no mention anywhere, not even the village in which she was born. But I am glad that there is a place where her story will be preserved,” Linda Austere emphasized during our correspondence.

“We ate the cat. I remember sucking on its ribs”

Well, let’s give the floor to Antonina Hnativna Boravika herself, born in 1925.

“I am from the village of Dubrovyntsi, Illinetsky district, Vinnytsia region. My maiden name is Honchar. There were four of us living: me, my mum Domtsia, my grandmother Mykhailyna, and my older brother Hrysha. I never saw or knew my father Hnat – he did not live with us… Maybe he left the family, or, maybe, he died – As a child, I was never told anything about that. My brother was older, but how many years he was older – I don’t remember.

My mother was very poor. We had a house. There was no barn, nothing, only a little house – a white one. There are such beautiful white houses in Ukraine… The little house had a large room and a stove. I remember how many icons my mother had. My grandmother, who lived across the hallway, had a kitchen and a small room with one window. There was a chest box and a table.

And we had everything: a bed, and a chest box, and a table, and a bench from wall to wall, and such shelves for storing dishes (mysnyk. – Author). We had everything we needed concerning furniture. The stove was good… They make good stoves there in Ukraine. Not like in Latvia, here they don’t know how to make that…

In 1933, there was a great hunger in Ukraine... Millions of people died. I was seven going on eight.

My mother and grandmother passed away on the same day. One morning, my mother woke me up and said: “Go get some milk – obrat” (obrat – skimmed milk. – Author.). I was crying, and I didn’t want to leave. It was April, the street was wet and muddy, the shoes were leaky, and mud was constantly getting into the holes. I was small but had to go a long way – the village was big. I said: “I will not go.” And mother: “If you don’t go, there will be no milk.” I was crying, but I took a half-litre bottle and left crying. Mother was still alive, lying on the stove.

One of Antonina’s last photos, her 86th birthday. 2011.

When I returned, I poured the milk into a small pot. I added more water and put it on the stove. And I didn’t know how to fire it up yet. I climbed up to my mother on the stove, and my mother was lying there on a pillow. The pillow was all wet, and the eyes were big, grey – looking up. I said: “Mum, mum, get up, you need to boil the milk.” And my mother didn’t answer anything… I climbed onto the stove – I pulled my mother’s leg, and her leg was heavy – it fell. I took my mother’s hand – her hand fell. Mum does not speak, in tears. She must have been crying when she was dying… And when I was leaving, she was talking to me!

I went to my grandmother in another room, saying: “Grandmother, my mother is not talking, but her eyes are open.” Grandma came, looked at Mum and said: “Domtsia died, Domtsia died…” And as she stood, she fell on the bed. She lay down for a while, went to her room, climbed on the stove, sat down, hugged her knees and died. And still, everything is in front of my eyes (crying).

And Hrysha, my brother, went and took a spade. That was in the spring, in April. He was digging in the ground in the garden, looking for frozen potatoes. Wherever he found potatoes, he pulled them out; they were frozen and soft but not rotten. We peeled them like this, put a little salt and straw, and fried the pancakes like this. They were delicious. He was digging the ground there, and I went outside shouting: “Hrysha, Hrysha, mother died.”

We had some relatives there, I don’t know from my mother’s side or my father’s, but close ones. My brother called them. They came, washed them, dressed them, and put them to bed. Mum – on the bed and grandmother – on the bench – a long one. And now I have this in front of my eyes…

They went to the collective farm, made two coffins and put both on one cart – mother and grandmother. They took them to the cemetery. There were five or six relatives. While they were going to the cemetery, they sat me on the coffin. Because how was I supposed to go? All around there was a swamp and dirt, my feet were cold and my feet were bare… And I was crying like a child crying. I remember my brother following the cart and saying: “Grandma, what will I do without you?” And crying… (sobbing).

At the cemetery I remember one old man telling me: “One grave, but two coffins.” When the hole was dug, a place was dug under the side for another coffin. And that old man said: “Daughter, look: mother will lie there, where by the side has been dug, and grandmother will lie straight”…

They buried my mother and came home. My brother was sent to the collective farm to get him something to eat. They gave some oats. We steamed some oats in a large cauldron and cooked it in the oven. Then we ate – it was very tasty, because there was hunger.

Do you know what we ate when there was hunger? We ate rats, and men dug up ferrets… My mother, I recall, took a cat somewhere, slaughtered it, and we ate it. The meat was delicious. I remember sucking the cat’s ribs.

So my brother and I stayed together. And my mother and grandmother died… Let my grandma, but my mother was very young…

We got up in the morning, but we had nothing to eat. I found some seeds from flowers. I remember they were called “chernushka”, so we boiled water to drink tea. The brother went to the garden to dig the ground again. Maybe, he would find some potatoes. And I found beetroot seeds and ate them. My stomach was swollen, and it hurt, and I was screaming. I went into the yard, rolling on the grass, shouting: “Mum, mum!!!”. The neighbour came: “What’s wrong with you?” I said: “my stomach hurts…” “What did you eat?” “Seeds…” She went home, brought me a spoonful of oil and gave me to drink. Then I threw up, and everything went out. I didn’t eat any more seeds…

I don’t know how many days passed… The small leaves started to appear on the cherries. I climbed a tree… A neighbour’s tree. There was a big house, and he (the owner. – Author) was sent to Siberia, so it was empty. But it was a lovely, good house. And there was a garden nearby, and many cherries trees were growing. I climbed on this cherry tree, took a little salt in my pocket, and picked some leaves; they were so sticky when I ate them, so I added a little salt… I heard Hrysha: “Tonia, Tonia!…” My name is Antosia, in Ukrainian. My name is such that you can call me in different ways. “Antosia, Antosia, where are you?” He must have already dug up these frozen potatoes… I said: “And I’m on the cherry tree, gathering leaves”…

We had a lot of acacia growing there. There were no leaves on the acacia yet, and last year’s seeds were falling. And so there were many, many of them. I sat under a tree, collecting them, opening and eating the little seeds. I ate, ate, and then I vomited, I threw up, and I ate again. Because I was hungry, I wanted to eat…

“Do you know what kind of soup? There was only water and a bit of grain of pearl barley”

So the days passed like that. And suddenly they opened a nursery in this empty neighbour’s house. They took me there. Some children who had parents came there in the morning. The orphans like me, and there were many of those whose parents had died, spent the night there.

There was a big room, and they gave us soup. Do you know what kind of soup? As in the proverb: “groats chase groats – the devil cannot catch up with groats”(it’s a Ukrainian proverb that means very little food, which is hard to find in the bowl.) There was only water and a bit of grain of pearl barley. At least it was something hot. And so they gave such a piece of bread. Tiny one. But at least something. I ate it once, and the second time I put it in a dress with a pocket and brought it to my brother. He was older, and he did not go to the nursery. I don’t know how he survived, but he survived.

As soon as they served dinner, I ate it, and after, I took it and ran away – I ran to sleep at home, which was nearby, to my brother’s. The headmistress came and, knocking on the window, said: “Antosia, Antosia, go to sleep in the nursery.” “My little brother is afraid to sleep alone.” “The head of the collective farm will shout, go,” she scared me because she was responsible for the children. I cried, leaving my brother and going, and my brother was afraid to sleep alone. Neighbours’ children were walking in the evening when it was dark and purposely scratched the window. Being scared, we climbed on the stove, and a small light bulb lit where there was a wick and a little kerosene, and it was burning. A fly flew over somewhere, and it was scary, and someone also scratched the window. And why were we scared?

I had to go to school in the autumn. They gave me a notebook, an ABC book, and a pencil and sent me to school. I had to walk far, and I was barefoot. My legs were dirty because I both ran and slept the same way; nobody washed them. And the dress was dirty because no one could wash it for me.

I stopped at the big gate of the school, and I was standing. The teacher came; his last name was Litkovsky, I remembered. Later the Germans shot him because he was a party member. This teacher did not have one leg, and he moved with crutches. “Did you come to school?” – he asked. He took me to the class, and there were other children. And you know, they were in shoes, and I was a poor girl, barefoot, my feet were cold… It was already autumn… But not a big deal… I remember writing sticks in my notebook, zeros…

Later, this nursery was turned into an orphanage. And I lived in that orphanage. And the cook was there; she made food for us: porridge, soup, potatoes, a piece of bread, and tea. They already fed us better than when I was in the first grade.

My brother did not go to school. I didn’t come to him then because I lived in an orphanage. I once met him on the street. He was walking, poor thing, and his pants were torn, the hole was so big, and his leg was tied with a rag. I said: “What did you do?” “I stepped on a nail and it hurts. I bandaged it.” I said: “Where are you going?” He must have gone to our parents’ house. He told me where, but I forgot and left.

For some time, the brother probably used to live alone. He dismantled our house and fired up the stove because there was nothing else to fire it. Then, perhaps, our relatives took him in. Because there was no house left. I don’t know what happened to it. I didn’t ask anyone about it. And when I went to Ukraine, I wasn’t interested. But I went to my garden and looked: the garden was clean. Our relative took it, as a relative’s garden was near ours, so he got the whole piece.

I had blue plums there. I remember we went to Ukraine twice already. In one place, there was a plum tree growing, it was small, but the plums were so big and red – and it still grew there. No one destroyed it.

And so the houses stood. The Kuchkovsky lived there – Leonid, Benedy, another Kuchkovsky, and others. The last time I went there with Raya (daughter. – Author), there were no houses left there. None! The elderly died, the young left and the houses were dismantled – there was a clear field. I was surprised when I went to my garden. But the land was ploughed, cleaned, people cultivated…

And the last time I saw my brother was when he was going to the army. Then Hrysha got into the Finnish war, where he died. I heard people talking that a notification had arrived that Hryhorii Honchar had been killed. That was already in 1939.

…I was already in the second grade, I was walking from the room to the corridor, and a woman entered. And the cook said to me: “Antosia, this woman has come to take you as her daughter.” She was my mother’s friend. Maria and her husband, Yakym Tkach, were childless and adopted me as their daughter. I felt good with them. I lived there from 1936 to 1939…”

“My grandmother’s holy desire was to return to Ukraine”

And here, Antonina Boravika’s impressive story ends. We managed to establish some details of her later life during correspondence with her granddaughter Linda Austere.

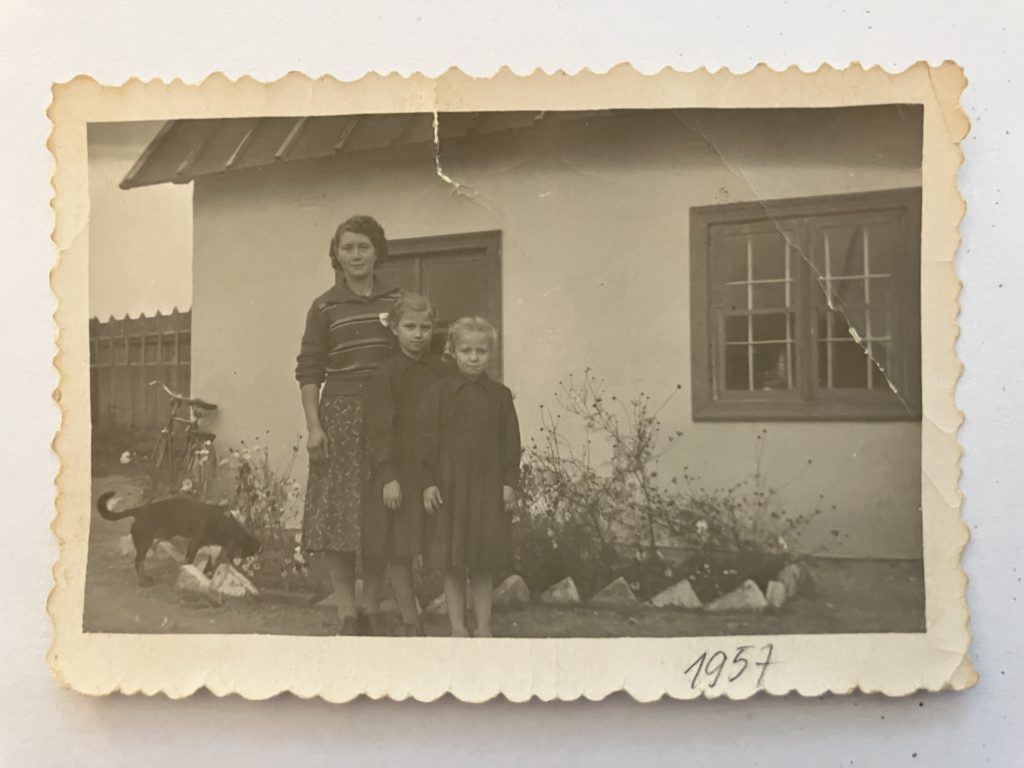

Antonina Boravika with her daughters Raisa (left) and Natalia (right), 1957

Together with Antonina, the Tkach family left for Russia, where they were promised land. But the family did not take root in Russia. They returned but did not have their own home, so they lived with relatives. As Linda Austere says, in 1939, her grandmother Antonina was sent (not forcibly, but rather to solve a desperate situation) to Germany to work. There is no way to clarify whether there is some mistake with the date. Antonina Boravika herself recalls that she lived with the Tkach family until 1939. And to get a job in Germany, as she told her granddaughter, she was allegedly even added to her age – made older. Linda adds that in the 90s, the grandmother was recognized as an ostarbeiter and received benefits from the German government.

Antonina got into a good family that lived on the border with Poland. When the front began to approach, her owners decided to leave. They invited Antonina to go with them. But she denied it because she dreamed of returning to Ukraine.

While there in Germany, she met a Russian soldier, “my grandfather”, as Linda writes, got married and went with him to Pskov. The young family did not stay long in the city, where post-war devastation reigned. Antonina and her husband found out that there was a job in Latvia and went there. That’s how fate threw the Ukrainian Antonina to Latvia, where she lived her whole life.

She never returned to Ukraine, but all the time, she continued to keep in touch with her adoptive parents – the Tkach family – until their death. Mrs Linda recalls that her grandmother showed her their photos in the family album…

Antonina’s first marriage did not last long. Then there was another marriage, but it was also unsuccessful. Ms Linda says she did not know either of her grandmother’s two husbands.

All her life, Antonina Boravika worked unskilled jobs: at a bread factory and as a nurse in a hospital. She received only primary education – only three grades. Since the Tkach family moved to Russia, Antonina could not attend school there because she did not know the Russian language. And then there was Germany. So she never studied and did not get a profession.

Antonina Boravika raised two daughters – Raisa and Natalia, both born in Latvia, and they gave her three grandchildren – Aigars, Gints and Linda.

From her grandmother’s stories, the granddaughter knows that she last visited her homeland in Vinnytsia in the second half of the 80s of the last century. Her village did not exist at that time.

“My grandmother’s holy desire was to return to Ukraine. She spoke Latvian perfectly, but she refused to assimilate. “I am Ukrainian, and I will never be Latvian like all of you,” she said. I am happy that she will finally return to Ukraine – with her memories,” Linda Austere wrote to us.

Turning this last page of her complicated and dramatic story, I think that if it had not been for the Soviet regime, Antonina Boravika would have had a happy childhood. And she would also have had her mother, grandmother and brother, and she would have known exactly what happened to her father. And in general, she would have lived a completely different life, and she would have had a Motherland. If only…

P.S. If you have relatives or know people who are the Holodomor eyewitnesses and can tell about them, please write down their testimony and hand it over to the Holodomor Museum. Or kindly let us know at [email protected].

Source: Texty.org.ua.