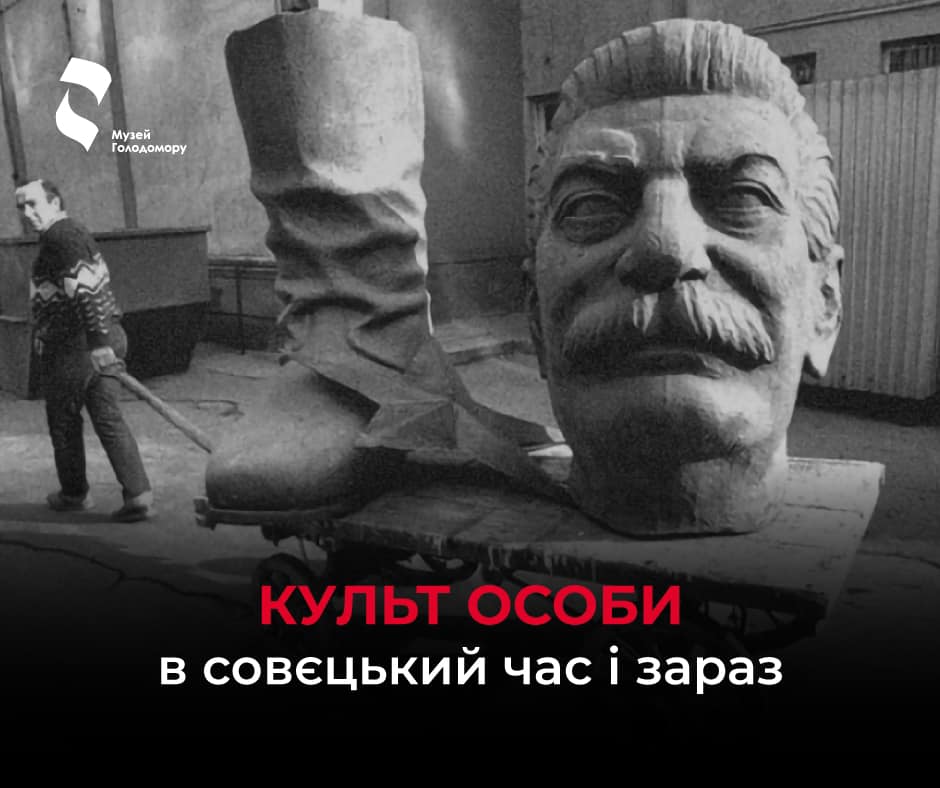

The cult of personality in Soviet times and now

Idealized and heroic images of political leaders are an essential feature of authoritarian and totalitarian states. The formation of the cult of the leader personality in such countries takes place as a practical embodiment of the idea that the leader is something more than a simple guide. He personifies the nation, statehood, revolution, and progress. Accordingly, the legitimization of the power of such a leader is not due to the efficiency and success of his rule but due to the fact that his very figure is declared a sacred value. Canonized stories about the extraordinary qualities of a single leader, ritual quotations from his works, and his standardized visual image, become the symbolic links that testify to the right delegated to the ruler by the people to rule at his discretion, without looking back at any laws.

During the 20th century, cults of the personality of political leaders existed in many countries: Albania (Enver Hoxha), Argentina (Juana and Evita Peron), Equatorial Guinea (Francisco Macias Nguema), Zaire (Mobutu Sese Seko), Iraq (Saddam Hussein), Spain (Francisco Franco), Italy (Benito Mussolini), China (Mao Zedong), Germany (Adolf Hitler), Romania (Nicolae Ceausescu), Yugoslavia (Josip Broz Tito), etc. Nowadays, the cults of the personalities of the rulers of the past continue to be preserved in Turkey (Mustafa Kemal) and Turkmenistan (Saparmurat Niyazov); in North Korea, both the former leaders Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il and the current leader of this country – Kim Jong Un – are worshipped.

The Soviet Union and Russia are textbook examples of societies that clearly gravitated towards the formation of a personality cult. Many researchers believe that the USSR was a modified form of existence of the Russian Empire, and Russians have a historical tendency to idolize their rulers. The most vivid example of such a social practice was the personality cult of Joseph Stalin, which existed in the USSR during 1929–1956. A less known fact is that other creators of the Bolshevik regime, in particular, Volodymyr Lenin and Lev Trotsky, were also surrounded by a cult of unrestrained praise and exaltation during their lifetime. Similarly, during the 1920s, cults of other communist leaders of a smaller calibre were formed, each of which was entrusted with a certain sphere of activity, as a kind of area of their dominance. In this way, Klim Voroshilov was called the “workers’ leader of the Red Army”, Hryhory Zinoviev – the “leader of the Comintern”, Serhiy Kirov – the “leader of the Leningrad Bolsheviks”.Monuments were erected to the leaders during their lifetime, and their images were reproduced in hundreds of thousands of copies on badges, tokens, post stamps, postcards, covers of school notebooks, caskets, handkerchiefs, campaign porcelain, art panels, etc. Only in the 1930s, with the establishment of the one-man cult of the personality of Stalin, the word “leader” in the Bolshevik idiom was finally established in the singular.

The personality cult of Stalin lasted until February 25, 1956, when on the closing day of the 20th Congress of the CPSU, the then leader of the USSR, Nikita Khrushchev, delivered a speech “On the personality cult and its consequences.” Debunking the cult of Stalin, M. Khrushchev immediately established the framework for permitted criticism of the dead tyrant without mentioning anything about the Holodomor of 1932–1933, mass repressions against Poles in the late 1930s, and many other crimes of the Stalinist regime. Contrary to the truth, M. Khrushchev assured that the cult of personality did not correspond to the “Leninist principles of collective leadership.” The Resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU dated June 30, 1956, “On Overcoming the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” contained very cautious assessments of the figure of J. Stalin, at the same time denying any attempts “to find the sources of this cult in the very nature of the Soviet social order.”

The cult of the personality of J. Stalin suffered another blow during the “perestroika” of the late 1980s and early 1990s. It would seem that the exposure of numerous crimes of the Stalinist regime finally turned this page of Russian history. However, after Vladimir Putin came to power in Russia in the first decade of the 21st century, the images of J. Stalin again began to appear in Russian public space, and more and more people in the Russian Federation went to rallies and demonstrations with his portraits. According to a survey conducted in March 2019, the role of Stalin in the history of their country was positively assessed by 70% of Russians, and only 19% of those surveyed negatively. Almost half (46%) of Russians noted that the crimes committed by J. Stalin were justified by “great goals and results.”

The cult of Stalin not only turned out to be significantly more viable than the communist regime of the USSR, but it also continues to develop in modern Russia, taking on such bizarre forms that Bolshevik propagandists would not even dream of. For example, since 2006, there have been periodic proposals in Russia to canonize Stalin, officially including him among the saints of the Russian Orthodox Church. Russian icon painters created several icons depicting J. Stalin.

Simultaneously with the revival of the cult of Stalin’s personality, the formation of the cult of Putin took place in modern Russia. Thanks to the Russian government’s control over television, this new cult was built with lightning speed. Pop artists sang songs about the Russian president, portraits of Putin appeared on T-shirts and other advertising products, and a sect was even founded that called itself the Church of Putin’s Witnesses. In a broad sense, the members of the pro-Kremlin youth organizations “Nashi”, “Iduschie vmeste”, “Molodaya gvardiya”, “Set'”, as well as the pensioners’ organization “Putin’s Squads” recognize themselves as “Putin’s witnesses”.

The modern cult of Putin, compared to the Soviet cult of Stalin, is much more flexible and technological. The main social function performed by the unbridled mythologizing and glorification of Putin’s figure is to impose certain standards of behaviour and social practices on society. The stories about Putin’s incredible “exceptional modesty”, “domestic unpretentiousness”, “incredible capacity for work” and “unbreakable will” justify the claims that the Russian government has the moral right to demand self-denial and patience from the people because through the figure of its “ideal ruler ” seems to demonstrate the best examples of asceticism and voluntary self-restraint.

In addition, Russian propaganda turned the attitude towards Putin into a “criterion” of patriotism. The essence of this false logic was expressed by Vyacheslav Volodin, an employee of the administration of the Russian president, with the words: “There is Putin – there is Russia, there is no Putin – there is no Russia.” The propagandists of the Stalin era did not allow themselves such a thing. However, there is not the slightest doubt that in the future Russians will have to learn to live without Putin and the traditional adoration of a one-man ruler in their history.

Andriy Kozytskyi,

candidate of historical sciences,

Senior Research Fellow

Holodomor Research Institute