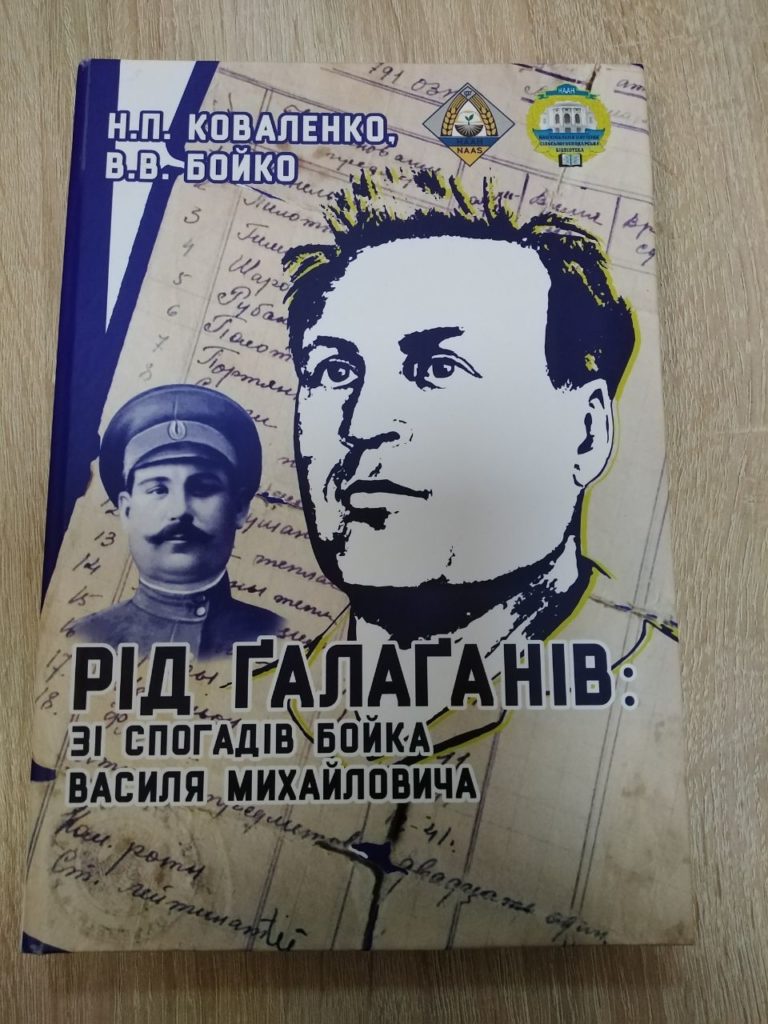

“The Galagan family: from Vasyl Mykhailovych Boyko’s memoirs”: a book of memories of the Holodomor presented to the museum

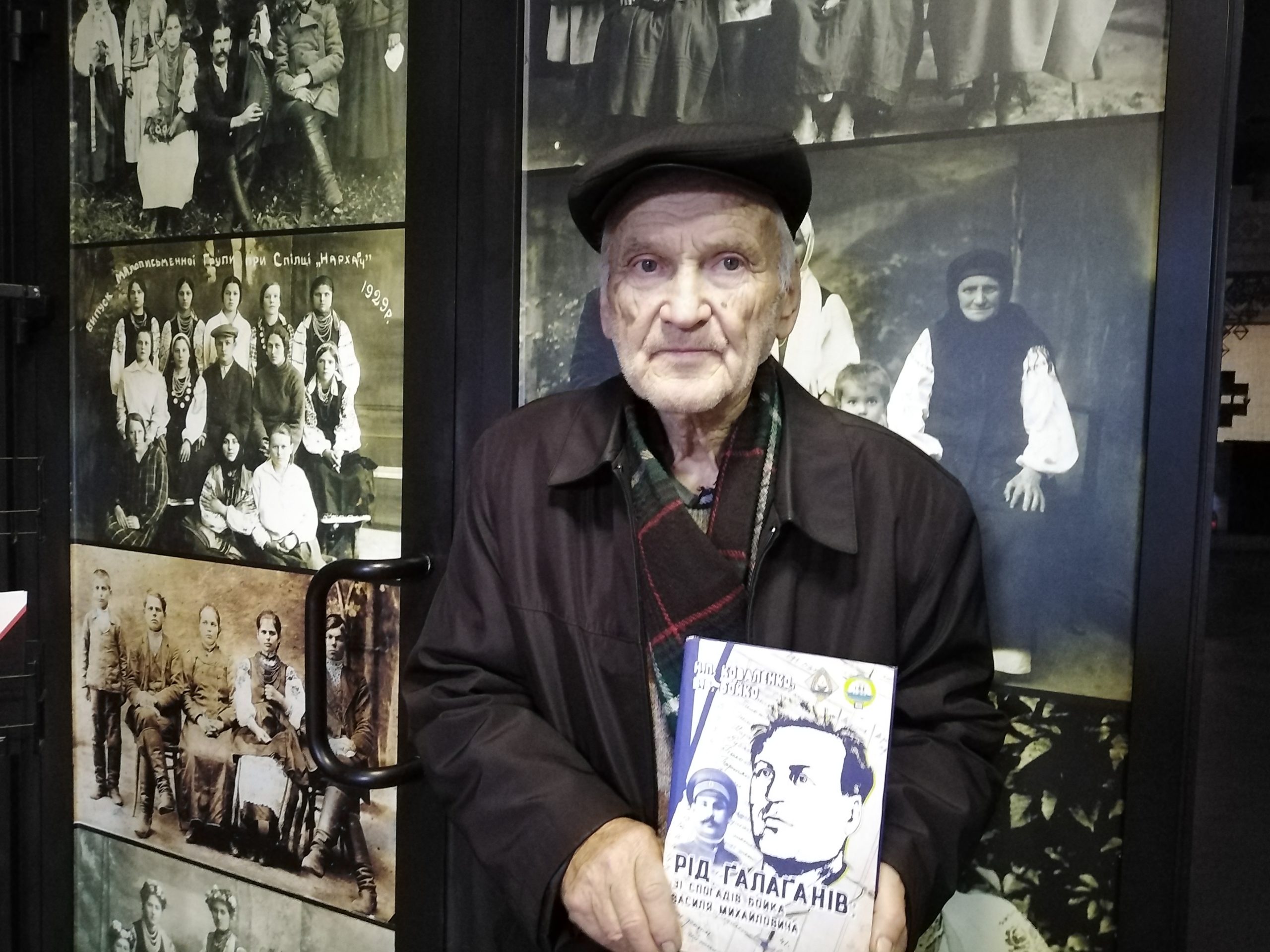

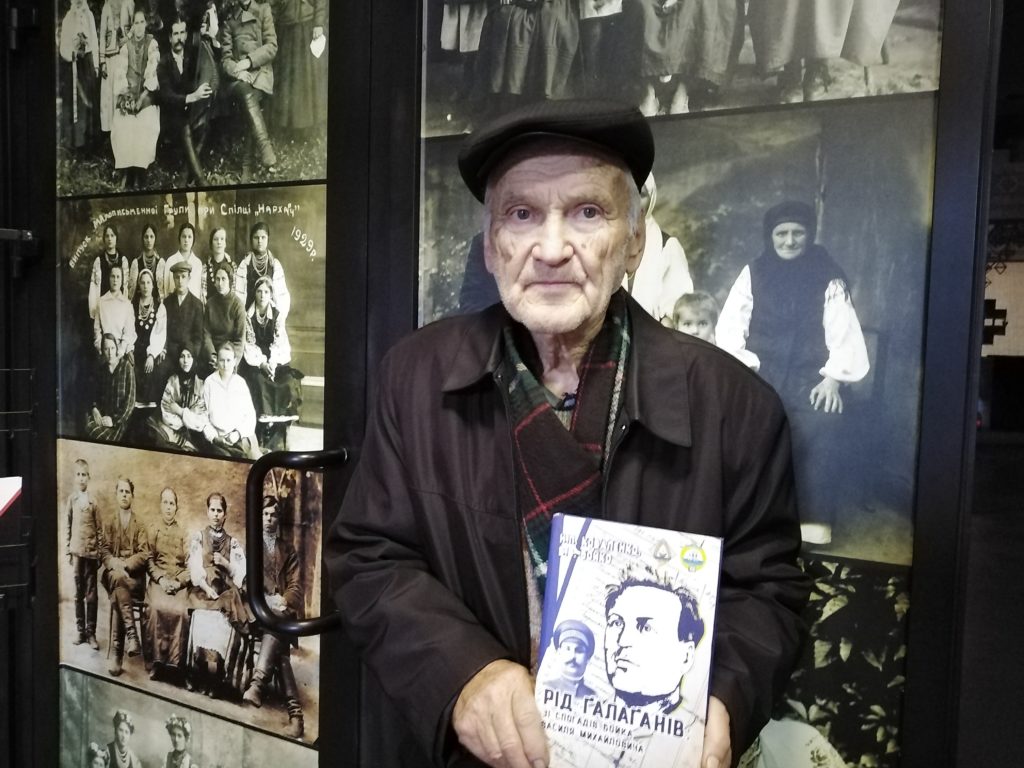

Petro Ivanovich Boyko visited our museum yesterday. The man came to present the book of his uncle’s memoirs to the museum, “The Galagan Family: From Vasyl Mykhailovych Boyko’s memoirs.”

These records were made in the 1990s at the request of his son Vitaly, a history teacher and local historian Vasyl Mykhailovych Boyko (born in 1916) from the village of Harkushyntsi, near Myrhorod, Poltava Oblast. As Vitaly Vasyliovych notes in the preface, at some point, he wanted to learn about his family’s past and asked his father to write down everything he remembered. Vasyl Boyko willingly set to work and worked on the manuscript for five years. Shortly after the thick notebook with 322 pages of handwritten text appeared, Vasyl Mykhailovych fell seriously ill and passed away… But his confession remained, covering a much longer period than the 82 years the author lived.

In his story, he did not miss the most tragic events in the life of his family and the whole of Ukraine – collectivization, dekulakization, and the Holodomor. The author describes in detail how they were forcibly driven to a collective farm, how confiscation commissions walked through the yards, which the farmers called grain extortionists, how they imposed unbearable taxes on individual farms, how the law on five ears of grain was in effect, how “they built socialism with obscenities and revolvers, not knowing pity for the old ones, not to the little ones.”

“Neither “black boards”, nor “blacklists”, nor sticks passed by our family… Just think, there were five mouths in our family, and the next day they would have nothing to throw in them. And no one in Kyiv or Moscow was bothered by this, Vasyl Boyko writes. – We were deprived of any salvation, like sheep in the slaughterhouse, peacefully awaiting their end. The house was somehow empty and sad. The “wise leader” left us one option – to wait for starvation. The sun was warming. Time to enjoy the spring. But there was no time for that. I was wandering around as much as I could, bringing young reeds from the floodplains of the Khorola River, and sorrel from the meadows. I plucked dandelions, acacia flowers, quinoa. I emptied the birds’ nests. Hunger, like a plague, exterminated fellow villagers. In the village, almost every day someone was taken to the cemetery, wrapped in linen. No one wept for the dead. Hunger erased everything human from the souls.”

“The culmination of the Holodomor was the spring of 1933. At that time, the policy of hateful forcible collectivization was intertwined with the policy of extermination of the kulak and the “expulsion” of farmers from the village was announced. My fellow villagers called this cruel policy “dery-bery”(means “take away-take”). In the spring, it was frightening to look at needy people. I remember Aunt Varka from the Kuzmenka village visiting us at that time. Her appearance resembled a martyr who appeared as if she came from hell. I remembered her thin, straw-like legs, which in some places were swollen from hunger, and her stomach as if filled with liquid…”

“Despite everything, the mass collectivization of peasant farms continued with the simultaneous grain procurement. For this, more than ten authorized officers were sent to our village, they had nagans with them… If grain was found in the yard, it was taken to the granary. All livestock were strictly registered. The owner had no right to slaughter it in order to save his children and themselves from starvation. If the owner slaughtered their own livestock, they were taken to court, the meat was confiscated and the family starved to death.”

“Horses were placed in adapted stables, but the newly appointed leaders did not take care of hay for them, grain fodder was not prepared at all. There was little of straw and chaff. That is why already in January-April 1933, horses began to neigh from hunger and die. They were often hung with ropes to the beams so that they wouldn’t fall down… Every boy ran there to look at the horses, help them, bring a handful of hay, straw, chaff, somehow support, have compassion on, perhaps, their former favorite…”

“Soon, Aliosha collected some stuff, took them to Kharkiv, and exchanged them for a bunch of rye, and on his way back home, the depeushniks (GPU officers) took that bunch at the border with Russia. So he returned home with nothing. The Bolshevik government dealt another blow to our middle-class family.”

The notebook with these impressive memories somehow ended up in St. Petersburg, in the possession of the author’s eldest daughter. For a long time, Vitaliy Boyko had sought to return the records to his home. And in 2018, he managed to get a photocopy of the notebook. With the family’s efforts, with the assistance of the National Scientific Agricultural Library of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and the National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine, these memoirs were prepared for printing and published in 2021.

“This book should be in every Ukrainian library,” Petro Boyko, chief researcher of the Institute of Agriculture of the National Academy of Sciences, Doctor of Agricultural Sciences, who became the scientific editor of the publication, says. – So that all would read and know what our long-suffering people went through. But the most unfortunate thing is that no one was ever punished for everything they had done.”

Petro Ivanovych Boyko at the Holodomor Museum.

We are extremely grateful to Petro Ivanovych for the gift and to the entire Boyko-Galagan family for preserving the family’s memory.

At the same time, we appeal to everyone who cares: If you have a Holodomor witness in your family, or there are such people among your neighbours or acquaintances, please record their memories (preferably on video or audio) or let us know. Today, it is crucial to have time to record these testimonies of the last eyewitnesses as evidence of the genocide of the Ukrainian nation.