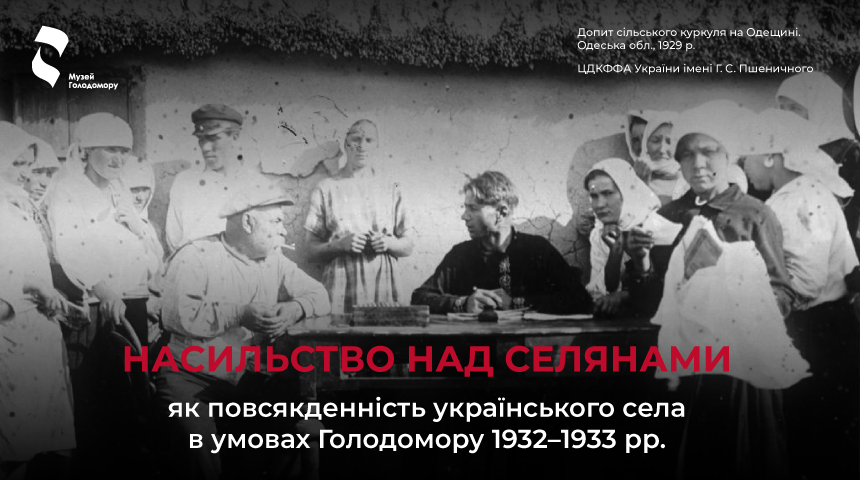

Violence against farmers was everyday life in the Ukrainian village during the Holodomor of 1932–1933.

The term “violation of revolutionary legality” used to spread in official documents of the party and Soviet institutions, bodies of justice and the DPU since the application of emergency measures during the grain procurement campaign of 1927/28. How illegal fines, searches, property expropriations, arrests, and the use of physical violence by government officials against farmers were classified as “criminal violations of revolutionary legality.”

The “violation of the revolutionary law” reached its peak during the grain procurements of 1932/33, when numerous harvesters literally raked out bread from a starving Ukrainian village. For example, in the village Lozovatka of the Kryvyi Rih district, authorized by the city party committee, Pushkariov and Kotov locked the peasant woman Hayska in a cellar for failure to fulfil the grain procurement, keeping her until evening, and then they beat her. And before she was released, she had been strictly warned not to tell anyone about it. According to incomplete data of the DPU of the Ukrainian SSR, from December 1932 to January 1933, such facts were recorded in 183 villages of 92 districts of Ukraine, and most of all in the Vinnytsia region – in 50 villages of 25 districts.

In the spring and summer of 1933, exhausted from hunger, half-dead Ukrainian collective farm workers began to be brought to work and were punished with beatings for absenteeism and non-fulfilment of work days. In this way, collective farm heads and foremen tried to overcome the “labour nihilism” of collective farm workers, who did not want to work for the state for nothing. For instance, a member of the village council of Forest Farms of the Nosiv District of the Chernihiv Region, Doroshenko, severely beat the collective farm worker Maslak for refusing to go to the field for ploughing.”

In total, during the harvesting and grain procurement campaigns of 1933, “violations of revolutionary legality” took place in 64 villages of 39 districts of the republic. Among the violators were 10 secretaries of labour centres, 15 heads of village councils and their deputies, 28 heads of collective farms, 7 foremen, 6 accountants of collective farms, 23 village activists, 4 district workers who were accused of illegal arrests, fines, beatings, abuse of farmers, and lynchings. The Central Committee of the CP(b)U emphasized that “beatings and abuses often took on an exceptionally brutal character”, as a result of which 24 people died from beatings out of 93 victims.

An idea of the scale of “violations of revolutionary legality” is also given by the materials of the investigation of the commission of the Central Committee of the CP(b)U, which during September 17–27, 1933, conducted surveys in 20 of the 36 districts of the Chernihiv region, studying the farmers’ complaints, the DPU’s information reports, judicial investigations cases, local authorities’ decisions. As a result, facts of “frank administrative arbitrariness bordering on political banditry” (beating and bullying of farmers, distortion of tax and penalty policies, mass appropriation and theft of illegally confiscated property) were recorded in 12 out of 20 districts of the region.

It should be noted that cases involving the use of physical methods of “education” of collective farm workers gained special publicity only in those cases when the victim of violence was a member of the Komsomol, a party, an activist, or udarnik (also known in English as a shock worker or strike worker who was a highly productive worker in the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, and other communist countries. The term derived from the expression “udarny trud” for “superproductive, enthusiastic labour”). At that time, the DPU bodies and the prosecutor’s office considered them “terrorist acts committed by a class enemy for the purpose of class revenge.” That is how they qualified for the beating by Lemish, the head of the collective farm named after Stalin of the Voroshilov village council of the Oleksandriysky district, a collective farm worker, M. Kovalenko, who died from her injuries.

The informational reports of the DPU bodies, the prosecutor’s office, and district party committees about “violations of revolutionary legality” prove that many local officials considered assault to be an integral element of any economic and political campaign. It explains some district and village leaders’ negative reaction to the directive instruction of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Ukraine (b) and the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated May 8, 1933, which declared the end of mass punitive actions against the peasantry. These leaders claimed that without the use of extraordinary methods of influence on the farmers, they would not be able to ensure the implementation of state sowing, harvesting, and procurement plans. Thus, Yareshko, the head of the Slobidska village council of the Putyvl district of the Chernihiv region, directly stated: “Now we cannot carry out campaigns, let those who signed this resolution carry them out.”

Thus, we can conclude that daily physical, economic, and psychological violence became a daily occurrence in the life of the Ukrainian village during the Holodomor of 1932–1933.

Natalia ROMANETS,

doctor of historical sciences,

leading researcher

Holodomor Research Institute

The National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide