A forgotten tragedy. One hundred years since the mass famine in the Crimea in 1921–1923

On 18 December, a public dialogue, “Mass famine in the Crimea in 1921-1923 and the Crimean Tatar people,” was held with the participation of Andrii Ivanets, a leading researcher of the museum. Based on the conversation, the article by journalist Mykola Semena was published on the Krym.Realii resource.

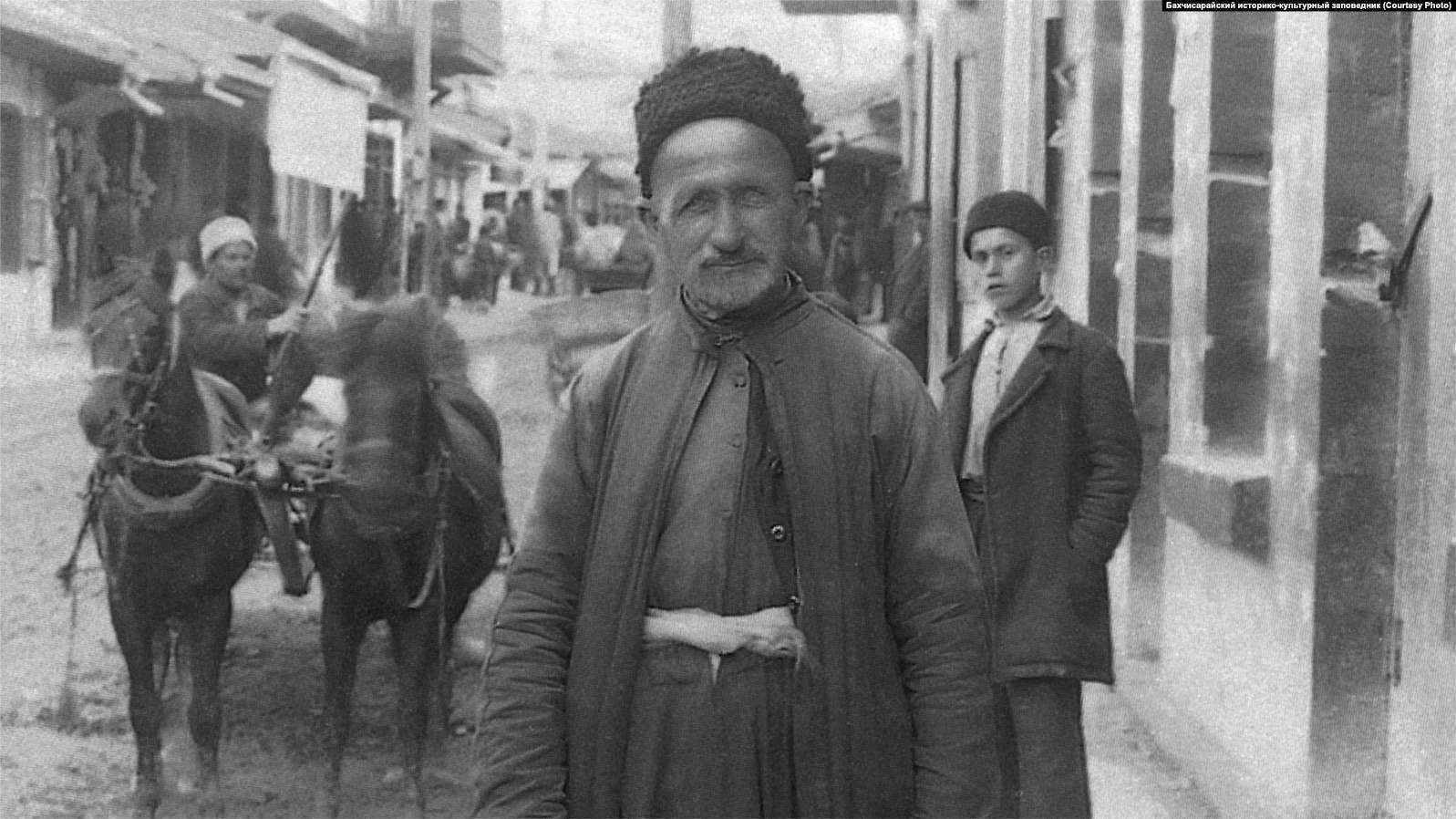

The famine of 1921-1923 was a severe blow to the Crimean population. Terrible demographic losses, due to which one in seven Crimeans died, were caused by the policy of the Russian Bolsheviks in Crimea, implemented against the background of natural disasters and devastation after several years of wars and revolutions.

Unfortunately, today, the mass famine of 1921-1923 has been almost forgotten, and there is still no monument in Crimea to the hundred thousand Crimeans who became victims of this catastrophe. Ukrainian historians still pay less attention to this historical fact than it should be. Even some Western scholars, if they mention the famine in the Crimea of 1921–23, consider it an insignificant event. Let alone the fact that Russian historians generally tried to hide this catastrophe from future generations. Meanwhile, the real death rate from famine in Crimea is impressive in its scale. Especially among the Crimean Tatars, it is disproportionately high compared to the rest of the population of the peninsula. The fact is, in part, that this tragedy was “overshadowed” by an even greater catastrophe – the genocide of the Crimean Tatar people in the middle of the 20th century, and therefore, no attention is focused on it. However, the famine in the Crimea in 1921–23 was part of the programmatic Russian policy in relation to the surrounding areas and non-Russian peoples, and this already makes us remember and talk about it.

On 18 December 2023, on the hundredth anniversary of the tragedy of the famine in the Crimea of 1921-1923, the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, the Treasury of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine, the Institute of Cultural Research of the National Academy of Arts of Ukraine and the Crimean Tatar public organisation “Alem” held a public discussion, during which it was revealed details of this tragedy and its victims.

Leading researcher of the National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide, candidate of historical sciences Andrii Ivanets, senior researcher of the Institute of Cultural Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, editor of the book series “Crimean Tatar Prose in Ukrainian” Nadiia Honcharenko, candidate of historical sciences, leading researcher of the National Museum Oleksii Savchenko participated in the public dialogue, who, together with the head of the NGO “Alem” Esma Adzhiyeva, are curators of the exhibition of Crimean Tatar applied art “MIRAS. Heritage”.

As Andrii Ivanets noted in his speech, today among criminologists there is no single point of view about when – autumn or spring of 1921? – the famine began in the Crimea, and about its real causes. This dispute can be put to an end by the words of Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev, a member of the collegium of the People’s Commissariat of the RSFSR, who reported on the situation on the Crimean Peninsula in mid-April 1921: “A terrible economic crisis… The food situation is getting worse every day. The entire Southern (consumer) district, inhabited mainly by the Tatar population, is literally starving at this time. Bread is given only to Soviet employees, and the rest of the population, both in cities and villages, receives nothing. Cases of starvation are observed in Tatar villages. Child mortality is especially increasing. At the regional conference of women of the East, Tatar delegates indicated that Tatar children are “dying like flies.”

Consequently, the beginning of a mass famine in the Crimea – the spring of 1921.

As for the causes of the famine, of course, one cannot discount such factors as winter with little snow and the following drought in 1921, unprecedented in the last 50 years, rains and an influx of locusts in 1922, the consequences of seven years of wars and revolutions, in particular, the mobilization of farmers and livestock, plundering of villages by white, red and other military and political forces. The lack of equipment also influenced. However, firstly, these reasons were not the main ones. Secondly, they could have been largely overcome if the state had taken measures to help the Crimeans in a hard situation. In addition, there were other reasons. However, the military and political events in the country only worsened the situation in the Crimea, which caused the tragedy. The situation was extremely aggravated with the requisition of food by the troops of the RSFSR, which conquered Crimea.

Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev wrote in 1921 about the economic bleeding of the Crimea by the Southern Front as follows: “After the conquest of the Crimea, as many as six armies were stationed in this small territory… All of them were fed at the expense of the Crimea, and each of them, leaving it, took a very large amount of “trophy products” , as well as horses… Separate Red Army units engaged in robberies, and no one could stop them…”

An important cause of the famine was the policy of the Bolshevik government in Russia. Despite the fact that 1920 turned out to be a bad year in the Crimea and only 7.5 million poods of grain were harvested, the Russian Bolsheviks imposed excessive prodrazverstka (food requisitioning) on the Crimean farmers. According to some estimates, it amounted to 2 million poods of food grain, 2.4 million poods of fodder grain, 2.4 million poods of fodder, and 80 thousand heads of cattle and other livestock. On the part of the authorities, a message was sent to Moscow (perhaps inspired by the centre) that the grain harvest in the Crimea in 1921 could amount to 9 million poods, while the actual gross harvest of grain was only 1.8-2 million poods. In connection with this, in the spring of 1921, the Bolshevik regime imposed an exorbitant food tax on the Crimea and exported food to Russia.

A major role in creating a situation of famine was played by the policy of the centre regarding the creation of state farms on the Crimean Peninsula. In December 1920, the Bolshevik authorities nationalised 1,134 landowners’ estates in the Crimea. However, most of their own land was not given back to the farmers. In 1921, more than 1,000 state farms were formed, which owned 1 million acres of land. As a result, most of the land transferred to state farms in the spring of 1921 remained uncultivated. In the autumn of 1921, due to the inefficiency of state farms and farmers’ protests, their number was reduced to 102, and 122,000 acres of land remained at their disposal. Moreover, a significant part of them functioned on the Southern Coast (Crimea), where the Crimean Tatar farmers prevailed.

Authorized by Kyzyltash village (now it is Krasnokamyanka, Yalta City Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea), Izzet Adan Mammut reported to the People’s Commissariat of the RSFSR that state farms used non-economic coercion against farmers. “Throughout the entire winter of 1920-1921, Kyzyltash residents were forced to transport firewood from the forest to Gurzuf to heat the electric station. Meanwhile, we farmers do not use electricity, but as serfs we must work for someone. After the onset of warm days, when spring work began in the gardens, they began to mercilessly exploit us. The South Soviet State Farm forces us to do all the work on the state farm at a time when our gardens, vineyards and tobacco plantations remained uncultivated… Now, when we do not have time to do our work, we are forced to work again, like serfs on the state farm, sent 15 miles from the village and threatening repressions.”

The policy of military communism and the prohibition of free trade played a detrimental role. This made it difficult, and sometimes impossible, for Crimeans to purchase the necessary products. A farmer who took products to the market was declared “the deadliest enemy of Soviet power and the workers’ and farmers’ cause.” Due to martial law, movement was difficult or sometimes impossible, so Crimeans from the affected regions could not always go to the less affected regions for food.

Moreover, in 1921, the starving Crimea was obliged to help the starving Volga region. Also, after the declaration of Crimea as an all-Russian health resort in 1921, 17,000 vacationers rested on its territory, which also worsened the food situation. At the same time, the Presidium of the Central Committee of the RSFSR recognised the entire territory of the Crimea as starving in just one year – February 16, 1922.

As evidenced by the documents of that era, the fear of hunger met at every step and impressed the imagination. Thus, Andrii Ivanets cited the following records of daily reports of the Crimean Cheka in 1922: 4 February: “The population collects the remains of skin and eats them.” 16 February: “Population eats cats and dogs.” 3 March: “The horrors of hunger are beginning to take on nightmarish forms. Cannibalism is becoming common.” 5 March: “The population began to eat grass and snails.” 11-12 March: “The father slaughtered his two little ones (children – ed.) and ate them together with his wife. He did not have time to kill the third one because he was arrested. He confessed to the murder and later died.” 13 March: “The starving masses subsist to a great extent on ox and sheep skins, and also take from the tanneries the remains processed and limed.” Since then, the number of missing children has increased to dozens in every city, and in Karasubazar in April 1922, a warehouse with 17 salted corpses, mostly children, was discovered.

At the same time, the majority of those starving were Crimean Tatars. Thus, the secretary of the Crimean Regional Committee of the RCP(b) and head of the Crimean Central Committee, Pomgol Yurii Haven, stated at the VI regional conference of the RCP(b) on 13-15 March 1922: “The famine here manifested itself in very sharp forms, it is not inferior to the famine in the Volga region. But it is not as eye-catching as in Volga. This happens mainly due to national and domestic conditions. Crimean Tatars are so connected to their village that even hunger cannot drive them away. And they quietly die in their villages… About 70% of the entire number of starving people are Tatars.”

Andrii Ivanets cited specific facts gleaned from contemporary documents. April 1922: “The population of Elbuzli in the autumn of 1921 consisted of 760 people, now there are 400 people left, all the others died of hunger. Velykyi Taraktash village. In October 1921, the population was more than 2,000 people. From November 1921 to 1 April 1922, over 800 people died of hunger. The village of Malyi Taraktash. In October 1921, there were 1,867 people, by 1 April, 1,152 remained, 715 people died of starvation… 299 of them were children. … There was once a case in Tokluka when a human corpse was dug up from a grave to eat. In the autumn of 1921, there were 1,092 people in Kozy, by 1 April of this year. 346 people died of hunger. … 3 cases of cannibalism were recorded…”

The local authorities of the Crimea at that time tried to help compatriots. For instance, on 12 May 1922, Yurii Haven and the head of the Crimean Tatar non-party conference, Osman Abdulgani Deren-Ayirly, telegraphed the Council of People’s Commissars of Azerbaijan: “More than 400,000 people are starving in the Crimea, that is, more than 60% of the entire Crimean population. More than 75,000 people, including more than 50,000 Tatars, died of starvation. More than a fifth of the entire Tatar population died of hunger.”

The consequences of the famine were catastrophic. According to Andrii Ivanets, gleaned from historical documents, the number of residents of Crimean villages decreased by 76,600 people, and the number of towns – by 75,500 people. According to various estimates, 66-75% of the 100,000-110,000 dead were Crimean Tatars. In Karasubazar, the number of residents decreased by 48%, in Old Crimea – 40.9%, in Feodosia – 35.7%, in Sudatsky district – 36%. Many villages of the mountainous Crimea completely died out. From 1 May 1921 to 1 January 1923, the total number of livestock on the peninsula also decreased significantly: horses – by 72%, cattle – by 62%, sheep – by 70%, pigs – by 92%, and goats – by 81 %.

In his speech at the public dialogue, the leading researcher of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine, and candidate of historical sciences Oleksii Savchenko noted that these facts are being made public for the first time in the Ukrainian scientific community, they are not known to many scholars in the West, and international organisations do not operate on them. However, the scale of this event shows that it was not insignificant, it is of world importance and should be introduced into scientific circulation.

Senior researcher of the Institute of Cultural Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and editor of the book series “Crimean Tatar Prose in Ukrainian”, Nadia Honcharenko presented her results of studying Crimean Tatar literature and spoke about those rare works that reflect the events and results of the famine of 1921-23 in the Crimea. There are not many of them but they confirm the terrible facts of suffering, death and other tragedies experienced by the Crimean residents in those years. She noted that the moral-psychological, historical trauma experienced by the Crimeans in those times has not been overcome to this day, and this requires new research, new discoveries and clarifications, a new study of historical documents and testimonies of living people, in order not only to show the inhumanity and criminal the nature of Bolshevik power but also to restore the historical truth and perpetuate the memory of the innocent victims of that terrible century.