Establishment of a collective farming system

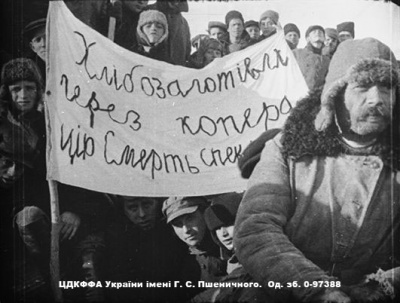

Holodomor was preceded by a policy of collectivization, which involved the forcible implementation of a collective economic system of state form. Ukrainian farmers, who were used to private ownership, did not accept the new system. Therefore, the introduction of collectivization was accompanied by coercion of farmers to join collective farms, terror, arrests and deportations of dissenters, which Soviet propaganda labelled as “kulaks”, “bourgeois nationalists.” The regime declared war against these people and destroyed them physically.

Before the collectivization in 1929, a major producer of agricultural products was individual farms. Farmers had a monopoly in producing grain crops (flax, hemp, hops, sugar beet) and animal products. Actions of Soviet powers such as taxing households, fines, expropriation, and destruction of wealthy households led to the so-called “grain problem”, a recession.

At the expense of collectivization, the Soviet authorities planned to solve several fundamentally crucial issues for themselves: to deprive the self-employed part of the agricultural population of freedom of action, to make a nationwide resistance movement impossible, to solve the “grain problem” by liquidating 5.2 million peasant farms and creating 25,000 collective farms on their basis.

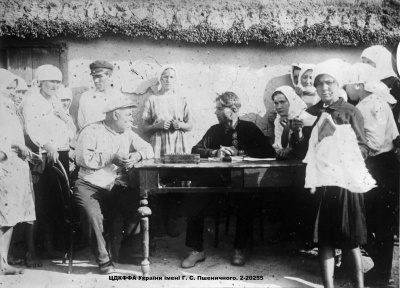

The regime started a class struggle, dividing the peasantry into classes: the poor, the middle, and the kulaks. The last of this classification were considered wealthy owners and enemies of the people. In May 1929, the Council of People’s Commissars presented the official definition of Kulak farming according to which a hired labour was regularly used in such a farm, or there was a mill, a butter factory, agricultural machines and premises were rented out; relatives engaged in commercial activities or usury or had other non-labour income, especially from being part of the clergy. As per these definitions, nearly every farmer could face punishment. The label “subkulak” was used for farmers who didn’t have their own farmland but resisted joining collective farms or showed disloyalty to the authorities. The vague definitions of “kulak” and “subkulak” broadened the scope of individuals who could be targeted as victims.

One way of ignition the class struggle in the village was to confiscate grains in the “kulaks” and distribute 25% of it among the poor and salaried workers. On December 27, 1929, Stalin declared the goal of eliminating “kulaks as a class”. On January 30, 1930, the secret resolution “On measures on liquidation of the kulak farms in the areas of complete collectivization” which included mass arrests, robbery and deportation of peasant families, was published. According to it, in the Ukrainian SSR, there were subjected to dekulakization of 3-5% of households. According to the categories, there were established penalties for “kulaks”. The first category was considered the most dangerous, as registered by the ODPU “for rebel organisations” imprisoned in concentration camps; the second category of kulaks was deported to the Northern Territory, Siberia, the Urals and Kazakhstan; kulaks of the third part were dekulakized and evicted within the area of residence.

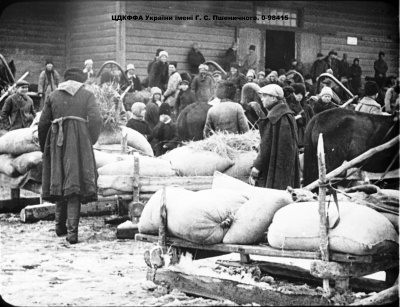

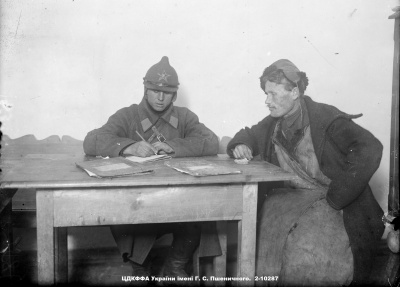

The district executive committee made the lists of “kulak farms” for eviction based on decisions of the meeting of farmers, labourers and the poor. Confiscation of the property was conducted by special authorised with the participation of the village council, chairmen of a collective farm and marginal groups. Property confiscated (means production, property, land, residential apartments) transferred to farms, and seized books and savings bonds – to the People’s Commissariate of Finance.

According to this resolution, by the end of 1930, 550 party functionaries at the district level were dispatched to places in the Ukrainian SSR to conduct measures to liquidate kulak farms. Workers sent to the village and village assets were actively involved in the expropriation of the wealthy owners’ property. However, the amount of assets in the total mass was not large. The most important role in the preparation and implementation of repressive measures against the “Kulaks” was played by the employees of the Joint State Political Directorate.

General information about Ukrainian eviction during deportations and expulsions to date has not yet been established by scientists. In the period from 1928 to the end of 1931, the number of farms declined by 352 thousand (over 1.6 million people).

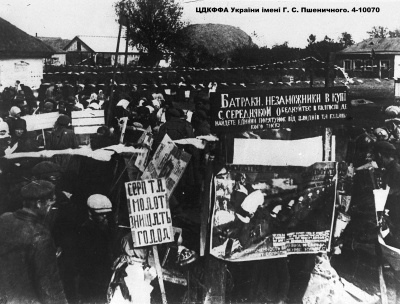

The government required that even small villages have prisons (before the revolution, they had existed only in district centres). These prisons were selected not only for fear of farmers who expressed dissatisfaction or voted against rural collective meetings. Resistance to collectivization often took on more violent forms. During the 1929 – 1930ss, tremendous efforts were made to prevent farmers from possessing weapons. The resolutions of 1926, 1928 and 1929 introduced compulsory registration of hunting weapons. In August 1930, with a small rebellion became clear that the resolution was not performed, and it was ordered to “hold great searches.” Of the registered OGPU in 1930 13754 (2.5 million members) of peasant unrest, riots and uprisings 4098 (more than 1 million participants) occurred in Ukraine. Some of them had a political nature: the participants proclaimed the slogan “Go away Soviet power!”, “Long live an independent Ukraine!” And sang “Ukraine has not perished …”

With the force with which the population’s resistance unfolded, with the same force its suppression and the policy of collectivization was carried out, the failure of which in Ukraine in March 1930 Stalin realised. At the same time, the authorities abandoned forced collectivization to regroup their forces in order to resume the offensive as soon as possible (imprisonments and deportations continued even during the Holodomor).

Ukrainians massively came out of farms, but the farms still had about 3 million households. In the first collective farm year, Ukraine performed a procurement plan due to favourable weather conditions in 1930 and a good harvest. However, the farmers were deprived of common stocks that traditionally made a living.

In 1931, the farmers were ignored, and the policy approved an excessive procurement plan, the implementation of which included confiscating maximum amounts of grains from collective farmers and individual farmers. Consequently, in many places, a hunger strike began. Soviet leadership was aware of the situation of the Ukrainian farmers, but it did not stop predatory grain purchases. In early 1932, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks demanded above-plan grain supply. From this period, the Soviet government began to artificially create Ukrainian living conditions designed for the partial destruction of the nation – the Holodomor.