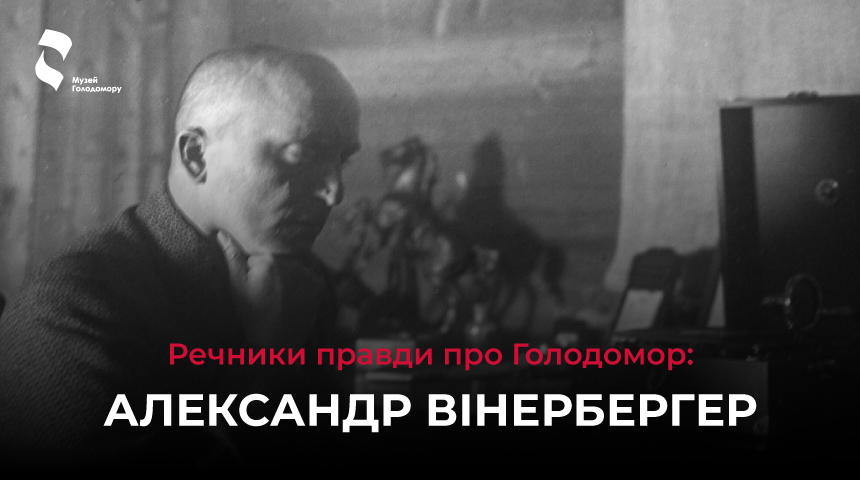

Spokesmen for the truth about the Holodomor: Alexander Wienerberger

The photos of the Austrian engineer Alexander Wienerberger are irrefutable evidence of the crimes of the communist regime. Wienerberger took them secretly and managed to smuggle them abroad through diplomatic channels. For more than half a century, the photographs were stored in the archives of the Diocese of Innitzer and цукуsaw the light of day only at the beginning of the new millennium.

Photographs most eloquently testify to the scale of the Holodomor. We can note that very few photographs of the period 1932–1933 have survived. This is also the result of the conscious activity of the GPU.

The unique photo collection was created by Austrian engineer Alexander Wienerberger. He spent 19 years in the USSR, working in chemical enterprises. During the Holodomor in Ukraine, he was appointed technical director at the Plastics factory in Kharkiv. Relatives from Germany gave him a Leica II camera, with the help of which Alexander recorded Soviet everyday life.

A Leica II camera that belonged to A. Wienerberger. The photo was taken in 2022 during the great-granddaughter Samara Pearce’s visit to the museum.

Realizing that it was dangerous to take pictures openly, Alexander used a specific detachable viewfinder, which allowed him to simply tilt his head down to take photos, instead of putting the regular viewfinder on the camera to his eye. Such a simple but unusual device made it possible to remain unnoticed because the people around did not even think that the person who bowed his head in front of the dead body was actually taking a picture. Perhaps the basis for the device was the usual removable angled viewfinder, which was produced both for the Leica I and the Alexander model. Or a homemade combination of several similar devices because there were models with the vertical placement of the eyepiece.

Leica II camera with angled viewfinder

Leica A camera with detachable viewfinder.

The pictures, taken by Wienerberger, show long queues for bread, and the streets of Kharkiv, where people were dying of hunger. The first one was taken in 1933. The photo below shows a man who died of famine on the streets of Kharkiv. Around him, there are the people of Kharkiv, who are anxiously looking at the deceased.

A. Wienerberger. Photo of 1933. TsDKFFA of Ukraine named after Pshenychnyi. Item 25000000006.

When Wienerberger returned to Austria in October 1933, he sent the negatives of the photographs by diplomatic mail through the Austrian embassy. Austrian diplomats insisted on this for security reasons: there was a risk that representatives of the GPU would detain Wienerberger when he crossed the border. Alexander Wienerberger gave the photos to the Catholic Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, thanks to whom the photos were kept in the archives of the Diocese of Vienna. For the first time, Wienerberger’s photos were published in 1935 as photo facts for Ewald Ammende’s book “Should Russia Starve?”.

In 1939, Wienerberger published his own memoirs, including two chapters on the Holodomor in Ukraine and supporting his claims with photographs. However, in 1939, Europe was on the brink of World War II. That is why the facts of the Holodomor, presented by Wienerberger, did not attract the attention of European politicians.

Roman MOLDAVSKY,

senior researcher of the department of historical research of the Holodomor-genocide

Holodomor Research Institute

National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide,

candidate of historical sciences, associate professor