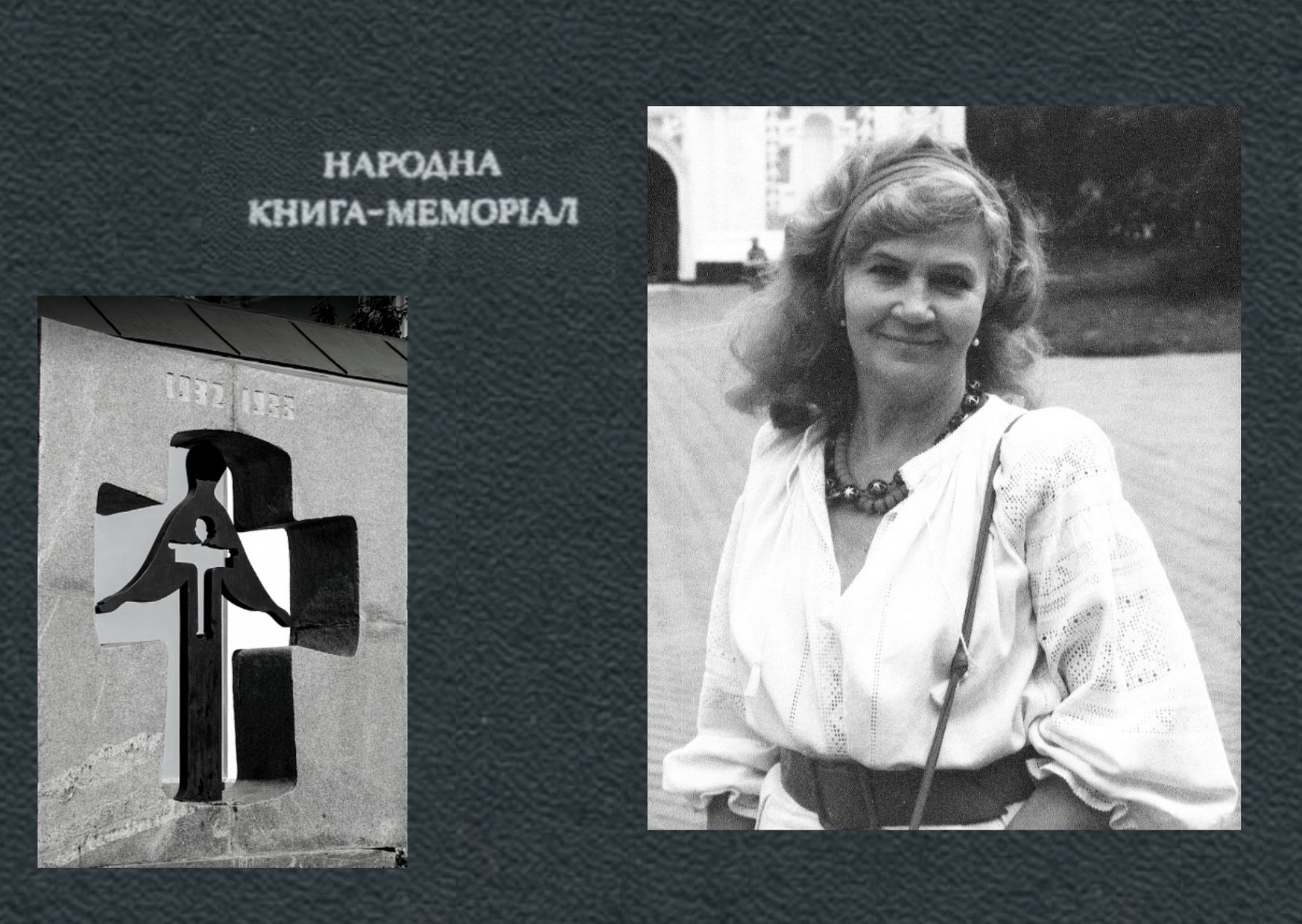

“We are stubborn: there will be no forgetting…” (to the 85th birthday anniversary of Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak)

This year, Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak, a Ukrainian public figure, journalist, and initiator of the Association of Holodomor Genocide Researchers, could have celebrated her 85th birthday. In honor of her memory, we publish a memorial article by Doctor of History Vasyl Marochko about this outstanding researcher.

“We are stubborn: there will be no forgetting…” (to the 85th birthday anniversary of Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak)

Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak could not read the interview “We are stubborn: there will be no forgetting…”. She died on January 23, 1993, and a conversation with Volodymyr Kulyk, editor of the Suchasnist (Modernity) magazine, was published almost simultaneously with her last breath. She could live for long time, but the physical, moral and psychological traumas she got in the mysterious accident of June 15, 1992, caught up with a professional journalist, writer, well-known public figure, the first head of the Association of Holodomor Researchers in Ukraine. With her husband Volodymyr Maniak, who died during the collision of a Mankivka-Kyiv bus with a truck, she managed to collect more than 6,000 memories of the Holodomor eyewitnesses, pass them through her own soul, organize and publish the first memorial edition in Ukraine (33rd: Famine, People’s Book-Memorial, Kyiv, 1991).

The memory of the Holodomor was not lost because the Association of Famine and Genocide Researchers of 1932–1933 in Ukraine (its first statutory name), which was created on the initiative of the Maniaks, managed to record tens of thousands of memoirs of the Holodomor witnesses, publish their collections, monographs and the Encyclopedia of the Holodomor (together with the National Museum of the Holodomor Genocide), to achieve its international recognition, and most importantly—political and legal assessment in Ukraine. Our memory of a horrible crime—the genocide of the Ukrainian nation—has not become overgrown with bitter wormwood, although there have been desperate attempts to stifle our sprouts of hope with dry ivy. We have the Law of Ukraine of November 28, 2006, the verdict of the Kyiv Court of Appeal of January 13, 2010, condemning the organizers of the Holodomor genocide, and the construction of the National Museum of the Holodomor Genocide.

Professional historians and political scientists have long debated the role and place of the individual in history. If a person is called by the creator to good deeds, then he is a benefactor, fulfilling his own mission of Christian charity. This is their historical role and place—to do good deeds: to have children, to plant a garden, to leave a good memory. When a person realizes their mission on a sinful earth, it becomes easier and calmer in their soul. A few months before her death, talking to Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak about the plans of the Association’s research activities, I could not even think about ending her earthly life. She did not seek glory, but hoped for a little attention, support from colleagues, and the righteousness of our journey to the Temple.

Lidiia Kovalenko was born on May 5, 1936 in a picturesque village of Bochechky in the Konotop region. She grew up in a family of teachers. In 1941–1944, she and her mother were evacuated to the Khorezm region of Uzbekistan, where she began her studies. Her father fought at the front, and the family returned to Chernihiv in 1944. Lidiia Borysivna decided to dedicate herself to journalism: in 1953–1958 she studied at the Taras Shevchenko University in Kyiv, later worked as an editor of several magazines, and in the 1960s as a correspondent of the Committee of Television and Radio of the Council of Ministers of the USSR. Her quiet voice and professional attitude were respected by colleagues in the magazines Morning and Ukraine, and in the early 1990s the magazine Man and the World, the deputy editor-in-chief of which she was, became the headquarters for the preparation of the constituent assembly Associations. Organizational work on its holding took place in the society “Ukraine”, the board of which was headed by Ivan Drach, as well as in the Union of Writers of Ukraine with active moderator Volodymyr Maniak (writer, chairman of the society “Memorial”).

The idea of creating not only the Association, but also an international research institute for the study of famine genocide in Ukraine arose in September 1990 at a conference in Kyiv. Its participants, in addition to Ukrainian historians, were James Mace, Orest Subtelny, and Marko Tsarynnyk, who did much in order to spread the historical truth about the Holodomor in the American and Canadian media. Nothing happened to the institute then, because the ideological cabinets were ruled by ideological supporters of Bolshevism or sometimes simply indifferent nomenklatura. People had to start with the public, unite historians, writers, journalists and witnesses of the Holodomor around the sacred cause—perpetuating the memory of its victims.

Volodymyr Maniak took over the organizational work on active coverage of the historical truth about artificial famine in Ukraine in the press. In February 1992, the organizing committee for the Association was established in the “Ukraine” fellowship, and initiative groups in support of it appeared in district and regional centers. On May 27, Volodymyr Maniak asked the board of Ukraine to finance the founding congress scheduled for June 27. Lidiia Borysivna, who edited the materials of the magazine Man and the World, was happy and appealed to the best human feelings. She corresponded with colleagues, consulted with us, historians, and her small office turned into a press club.

The first spring and summer swallow of the Association’s birth was its organizational center at the Institute of History of Ukraine of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. It was founded on June 1, 1992, and applications for membership were written by Vasyl Marochko, Serhii Kulchytskyi, Olha Movchan, Yevheniia Shatalina, Oleksandra Veselova, Serhii Kokin, Borys Zakharchuk, Heorhii Kasianov, Mykola Doroshko, Vasyl Boiechko and others. Vasyl Marochko, Candidate of Historical Sciences, was elected the head of the center. Historians of the Institute Vasyl Marochko and Yevheniya Shatalina had already published archival documents on the famine at that time and provided them for the organization of a memorial publication prepared by the Maniaks. The Writers’ Union agreed to hold the convention. Everyone was waiting for a significant historical event, as it was the first public association in Ukraine to study the famine genocide.

In early June, in order to stimulate public opinion and persuade people to take the initiative, Lidiia and Volodymyr agreed to take part in the unveiling of one of the first monuments at the mass grave of the Holodomor victims. It was to be opened on June 14, 1992 in the village of Tymoshivka, Mankivka district, Cherkasy region. Lidiia and Volodymyr invited me to take part in the memorial events, but for some reason I could not go with them. On June 15, returning to Kyiv, they died under strange circumstances: a truck crashed into the bus. Volodymyr died immediately, and Lidiia removed a watch from her husband’s severed hand, which recorded the time of the end of his earthly life. On the same day, perhaps a few hours later, she informed me of the terrible circumstances and asked me to make a keynote address at the meeting of the Association. I don’t know why she offered it to me, because there were colleagues who worked closely with the couple at the time. In particular, the historian Illia Shulga from Vinnytsia actively interacted with them. Lidia could not deliver a report due to physical injuries, which were visible, not to mention the bitterness of losing her husband.

The founding congress of the Association of Famine Genocide Researchers took place on June 27, 1992 in the assembly hall of the Writers’ Union of Ukraine. It was attended by 58 delegates from the regional divisions, 16 invited guests, including a representative of the Ukrainian diaspora from the United States Marian Kots—the soul of the Association, its patron. Lidiia Kovalenko chaired. She invited people’s deputies of the first convocationIvan Drach and Zynovii Duma (historian and deputy Arsen Zinchenko was in the hall), Marian Kots, Ruslan Pyrih, Borys Sadursky, Volodymyr Hula, Oleksandr Mishchenko, Vasyl Marochko, Dmytro Kalenyk (12 people died of starvation in his family) to join the presidium. The atmosphere was incredible—emotions, political statements, memorial appeals. In the crowded hall, there were the representatives of the Ukrainian Vasyl Stus “Memorial”, the “Prosvita” Society, two academic institutes (the Institute of State and Law and the Institute of History), even a representative of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine colonel Volodymyr Mulyava, as well as the press. In his introductory speech, Ivan Drach noted with his inherent oratory: “The time has come when all conscious Ukrainians must proclaim to the whole world and demand recognition of the famine of 1932–33 as an act of genocide of the Soviet empire against the Ukrainian nation, against the Ukrainian farmers as a base of the Ukrainian National Republic, which was established in 1918 and did not obey the Moscow Empire, its encroachment on land, subsoil, property and achievements of the UNR. Our ancestors demand this of us. We must name all the victims of the famine genocide, remember them, tell our children, grandchildren, the world. We must name those who committed this genocide so that it will never happen again.” Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak invited me to speak. I delivered the founding report “On the Establishment of the Republican Association of Researchers of the Famine Genocide of 1932–32 in Ukraine”, in places interspersed with emotions and excitement. Delegates approved the charter. Historian Ruslan Pyrih proposed to elect Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak as the chairman of the Association Council. Subsequently, the Council was elected from 25 people: deputies, historians, journalists, eyewitnesses of the Holodomor, representatives of local branches.

Lidia Kovalenko-Maniak stood behind the rostrum of the meeting. In a low voice, with pauses and sighs, after which the hall froze, she proclaimed several key points, “The main aim of the Association is to study the history of the Holodomor of 1932–33 and name the perpetrators of this act of genocide, to erase the blame from the Ukrainian farmers. To tell the whole world that the famine of 1932–33 was an artificially organized famine, one of the acts of genocide of the totalitarian Soviet system against the Ukrainian nation.” She offered delegates, society and the government a number of memorial and institutional events. Quiet, modest and broken by life woman.

Today, remembering that fateful moment, I think about the role of a person in history. June 15 comes to my mind. God saved Lidiia Borysivna, but took away her friend, colleague, husband, father of their son. Probably, someone would refuse to complete the case of historical significance, but not her. Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak felt her mission and gave the organizational movement a strong emotional and memorial impetus to create the Association. The convention took place. Gaining intellectual momentum, the Association began to operate. She did not allow the memory of the Holodomor victims to be trampled on, and tens of thousands of their memoirs were collected and published. On the day of the meeting, speaking from the rostrum, Marian Kots thanked Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak for the book “33rd: Famine”, with which she initiated “the repentance of our people before the victims of genocide”, and donated their own funds to hold a competition for the best musical work, a requiem, proposed to the President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk to establish the annual Day of Remembrance of the victims of the famine-genocide of 1932–33 and to start a competition to create a monument to the victims of the Holodomor in Kyiv.

The Council of the Association, which coordinated the work of local branches, met in the “Ukraine” fellowship building on Zolotovoritska 6. The room was allocated to us by the fellowship chairman Ivan Drach. We were then preparing to participate in the World Forum of Ukrainians, which was to take place in the summer in Kyiv. It was decided to hold a “round table”, which after the international symposium in September 1990 was the second large-scale memorial-academic event. Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak instructed me and my dear colleague Vadym Mytsyk to collect items of village life (millstones, household items, etc.), as well as to form a list of participants. The round table meeting took place in August 1992 on the territory of the Taras Shevchenko Museum with the participation of the Ukrainian diaspora, deputies and the public. Upon completion, daily research work, collection of archival documents, eyewitness memoirs began. From memorial appeals we went to specific scientific and historical affairs.

On November 11, 1992, Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak addressed the representatives of the President of Ukraine in the districts with a request to support the initiatives of the Association. She emphasized in her letter: “We have appealed to the heads of all churches in Ukraine to hold memorial services for 8 million of our compatriots killed by starvation. Our requests have been heard, and the dead are already commemorated in churches today. I am sending you recommendations on arranging the graves of victims of genocide and we ask you to start working with the population of your district to prepare for the celebration of the sad anniversary. ” A number of other memorial events were also proposed. At that time, the authorities and the public took parallel courses, sometimes intersecting in similar letters. There was no initiative from state bodies, let alone from the communist Verkhovna Rada of independent Ukraine. However, they didn’t bother us much, but they didn’t help us either.

In November and December of 1992, the Association honored the memory of Holodomor victims, “promoted” articles in newspapers and magazines in Ukraine and abroad. Lidia Borysivna recorded an interview with Volodymyr Kulyk, the editor of the political science department of the magazine Suchasnist, and also invited me to publish my report at the congress, giving it a journalistic direction. Traumas overtook her, and she worked very hard, rethinking her own journalistic past. Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak explained the prehistory of the Association and the beginning of the memorial movement in Ukraine. “The association was born out of a living need. As soon as 1992 began, many people remembered the approaching 60th anniversary of the Holodomor. Somewhere from the Intercession of 1932 to the Trinity in 1933 was its apogee: a million Ukrainians fell to the ground every month. This terrible figure, eight million deaths in eight months, must be remembered today by those who resort to risky experiments on the people.” In the early 1990s, a sacred cause was the compensator for the troubles in Ukraine, which was gripped by coupons and material troubles in the transition period. Lidiia Borysivna felt it, as well as the passing of time, although then she was only 56 years old. She considered the sad date—the 60th anniversary of the Holodomor—a last resort: ten years from now, as “the children of the 33rd are now testifying.” She seemed to be urging us, “So if not now, when? If not us, then who? ”And considered her main task to collect and organize documents in order to “recognize the famine as an act of genocide, a crime against humanity and humanity.” An educated journalist, a wise and educated woman, she was well acquainted with the political and historiographical details of the problem of international recognition of the Holodomor genocide. “Not everyone in the world likes to talk about our famine. The world is not as generous to Ukraine as we would like it to be. The world has betrayed Ukraine more than once, it betrayed it even when there was famine. The Prime Minister of France Edouard Herriot arrived in Kyiv, before the corpses were removed from Khreshchatyk (or Vorovskoho Street), he returned to France and announced that there was no famine in Ukraine,” Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak said. She perceived the theme of genocide not only in the context of the history of Ukraine, but also as a “tragedy of all mankind.” For her, the Holodomor was not a coincidence, because it was “brought by the Moscow-Bolshevik totalitarian regime” and “a purposeful policy of destroying the Ukrainian people.”

In an interview, Lidiia Borysivna mentioned Robert Conquest’s book The Harvest of Sorrow, which she considered “the most honest book ever written about Ukraine by a non-Ukrainian.” Apparently, the topic of the famine caused her personal feelings, superimposed on the pain of the loss of not only 8 million Ukrainians, but also the family. Her phrases “On June 15, my husband, who was the chairman of the Organizing Committee, died in a car accident” when “we were returning from the village of Tymoshivka in Cherkasy region, where they took part in the unveiling of the monument to the Holodomor victims” do not leave me to this day. I wrote an article that Lidiia Borysivna asked me about at the time, and the magazine Suchasnist published it in its second issue in February 1993.

At the end of 1992, she hoped for the implementation of memorial events, which she personally or collectively worked with us, because “we can not miss the first months of 1993, because in those months sixty years ago, Ukraine was already a continuous impenetrable cemetery.” At that time, the Association constantly demanded that the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine “qualify the Holodomor as a deliberate act of genocide against the Ukrainian people committed by a totalitarian state.” In fact, all the proposals voiced by Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak were implemented today, and even the National Museum of the Holodomor Genocide operates, which we could only dream of in 1992. Our national feelings have not been overgrown with wormwood, and the bitterness of the loss of more than 8 million Ukrainians still amazes us with its scale.

After her personal loss, Lidiia Borysivna was not alone, because she constantly worked with us, received many letters from Holodomor witnesses—she recieved more than 6,000 testimonies at her home and business addresses at that time. Probably the best mention of our colleague should be her symbolic words: “Candles were lit all over Ukraine from our candle.” So, let not our candle of memory of the colleague, the devotee of sacred and merciful business, Lidiia Kovalenko-Maniak, be erased. She did not have time to receive high state awards for life: the Taras Shevchenko State Prize of Ukraine (1993) and the Order of Princess Olga of the 3rd degree (2005) she was posthumously awarded. However, the best reward is a bright memory of her colleagues, admirers of her work, deeds and thoughts.

May 1, 2021, Vasyl Marochko